As CDC reverses itself on COVID-19, Americans are losing trust, warn public-health veterans

The agency abruptly changed its guidance on testing and how the coronavirus spreads.

People who are exposed to a COVID-19 patient but feel fine don’t necessarily need to get tested, the nation’s top public health agency declared in August — only to drop that advice last Friday.

The same day, it declared that the coronavirus could spread beyond the 6-foot social distancing threshold, borne by “aerosol” particles that remain aloft for minutes.

But this week the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention took down that update, too, saying it shouldn’t have been posted without review.

The reversals have alarmed veterans of the public-health community, warning that they could fuel confusion and even mistrust of science as a pandemic that has claimed 200,000 U.S. lives shows no sign of letting up.

Changes in health guidelines are to be expected as new scientific evidence emerges, said Esther Chernak, an associate professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health. Think of the advice on masks: At first, they were not thought to be necessary outside hospitals, then evidence emerged that they were.

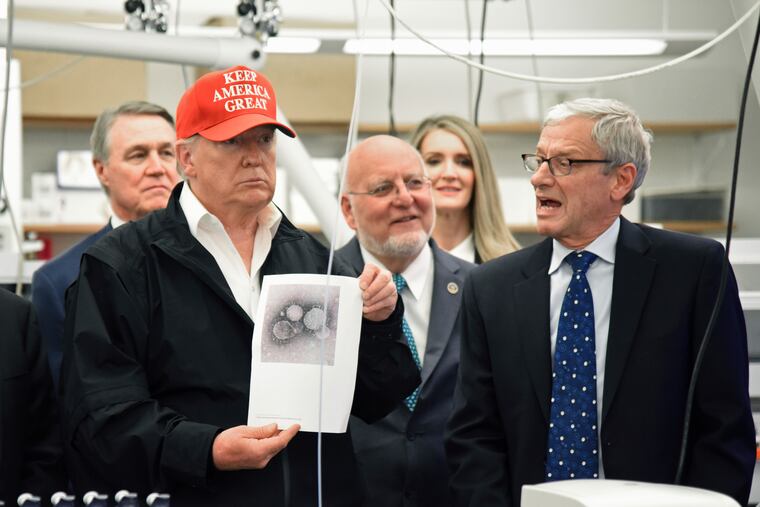

What is worrisome is when changes in public health policy are driven by non-scientists, she said. It is unclear what prompted the switch on how the virus is transmitted, but the CDC’s looser guidance on testing was pushed by the White House coronavirus task force, according to the New York Times. President Donald Trump has frequently claimed that the nation already does too much testing, though medical authorities almost universally say the opposite.

“I don’t think it’s random what goes up and down on [the CDC] website," Chernak said. "My concern is that it is more controlled by people with more of a political orientation than a scientific orientation.”

That sentiment was echoed by former Philadelphia Health Commissioner Donald F. Schwarz, now a senior vice president at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the Princeton-based health philanthropy.

“What we’re seeing is a perversion of the review process,” he said. “It undermines our faith in our ability to use the information.”

Both Chernak and Schwarz said they still have utter faith in the career scientists at CDC. The Atlanta-based agency, founded after World War II initially to fight malaria, is a leading global authority on all kinds of health conditions. But both said they were troubled by recent reports that the agency’s weekly research digest was being reviewed by political appointees at its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services in Washington.

That digest — a dispassionate distillation of science called the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) — is held by epidemiologists and physicians in the same esteem that the business community holds the Wall Street Journal. Among its most famous dispatches is a September 1982 report that named a new form of immune deficiency: AIDS.

“If you want to know what’s going on from a disease perspective in the United States, you read the MMWR,” Chernak said.

Articles in the digest always have been subject to review, but careful science has been the ultimate guidepost, Schwarz said.

Yet in a report from Politico, CDC officials said they had been pressured to change summaries of COVID-19 data so as not to contradict Trump’s optimistic messages of progress.

CDC scientists have fought back against the most substantial changes but have compromised on wording in a few cases, Politico reported, citing three people familiar with the situation.

Following the uproar, Michael Caputo — a senior administration official who was accused of interfering with the weekly reports — took a leave of absence. Caputo, a Health and Human Services spokesperson, had accused scientists of conspiring against the president, then apologized to his staff.

In August, the CDC’s looser guidance on testing drew fierce pushback from physicians and other public-health experts, who warned that a failure to test people without symptoms would prevent health departments from identifying a significant source of disease spread.

Harold Varmus, a former director of the National Institutes of Health, coauthored a New York Times column titled “It Has Come to This: Ignore the CDC.”

The revised testing guidance, posted Friday, allayed such concerns — recommending a test for anyone who has been within six feet of an infected person for at least 15 minutes, whether or not they experience symptoms.

The abrupt removal of the update on aerosol transmission, on the other hand, stoked new concerns that the agency was steering the public in the wrong direction. Epidemiologists have documented numerous cases in which the virus has been transmitted farther than six feet, particularly in indoor settings with poor ventilation.

Chernak, director of Drexel’s Center for Public Health Readiness and Communication, said that sudden changes in messaging, when not accompanied by clear, evidence-based explanation, make fighting the pandemic more difficult.

“How you communicate with the public, how you explain risk, particularly when people are fearful and upset, is as important as the steps to actually curb transmission in the community,” she said. “It’s not just a communications failure. What we have is a failure of response and a failure of policy. Everyone recognizes that responding to a pandemic is hard enough.”