COVID-19 has more Americans thinking about science. Could this be a Sputnik moment?

Experts in science communication and the psychology of persuasion say it is possible to make inroads with those who resist evidence and expertise. Difficult, but possible.

The world is grappling with a deadly threat, though its seriousness has been downplayed by the president and proposed solutions are rejected by those who insist that the economy will suffer. Yet more and more people say they accept the science underlying the threat.

The coronavirus? No, climate change.

Public understanding of science may seem weak these days, with social media full of unproven claims about various COVID-19 treatments, and bizarre ideas such as the pandemic being linked to 5G radiation from cellphone towers.

But from their experience with other politicized scientific topics such as climate change, experts in science communication and the psychology of persuasion say it is possible to make inroads with those who resist evidence and expertise. Difficult, but possible.

The solution includes careful, patient explanations, delivered respectfully. That’s crucial, whether you’re talking to a family member or presiding over a news conference. An attitude of “just trust us, we’re the experts” is no good.

“Invite the audience to share in the act of looking at the evidence,” said Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

Polls indicate most Americans now accept that human activity has caused an increase in average global temperatures, a process that has unfolded over decades.

Shouldn’t it be easier to build public appreciation for science during a pandemic that is striking down people in just days?

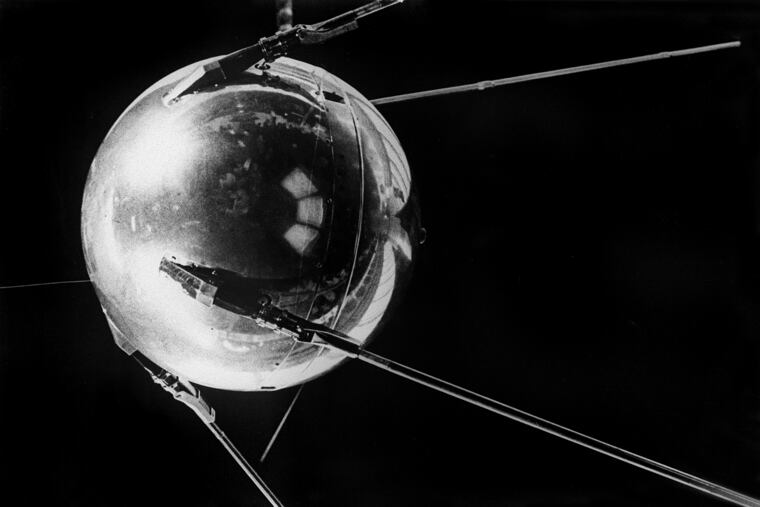

Many have called for a “Sputnik moment” type of urgency, evoking the Soviet satellite launch in 1957 that galvanized U.S. investment in research and education. And there is no question that scientists have responded, studying the biology and possible treatments at a head-spinning pace. The Russians have even named their vaccine after the satellite.

But for a variety of reasons, the public-appreciation part of the equation has not gone so well, and that has stood in the way of what everyone wants: to get back to normal.

The remedy, science educators say, might need to start as early as elementary school.

When science is wrong

On July 16, four months after President Donald Trump declared the coronavirus a national emergency, Anthony Fauci made an admission that the general public does not normally associate with scientists.

He said he was wrong.

The topic was masks. The U.S. government’s initial advice was not to bother with the face coverings, because the real risk of airborne transmission was believed to be in hospitals, not out in the world, explained Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984 and a pioneer in studying HIV.

But evidence emerged that infected people who had no symptoms were spreading the virus, just by singing, shouting, even ordinary conversation. So cloth masks made sense for everyday use, Fauci said in an NBC interview with Facebook chief executive officer Mark Zuckerberg.

“As the information changes, then you have to be flexible enough and humble enough to be able to change how you think about things,” he said.

That’s how science works: When new evidence emerges, new conclusions may follow. But the unfortunate takeaway by some was that Fauci was not to be trusted, said Penn’s Jamieson.

“We shouldn’t be saying, ’Scientists, you were wrong,’” she said. “We should be saying, ’I’m glad the scientists have new knowledge.’”

What’s different with COVID-19 is that the process is happening in an unusually public and accelerated fashion, said Ann Reid, executive director of the National Center for Science Education.

In her previous job at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Reid helped decipher the genetic code of a virus that caused a different pandemic: the 1918 flu. It took seven years.

With modern technology, the genome of the coronavirus was pieced together within days. The rest of the discovery process has been compressed, too: the publication of results, the reviews by academic societies, the transition from basic research to the development of treatments. It is bound to seem messy.

Schools must teach students to weigh the body of evidence, rather than throwing up their hands and declaring they don’t know what to do with conflicting studies.

“I don’t really care that students remember the details of Linnaean classification,” she said, referring to how living things are sorted into species. “I want them to be able to think like a scientist.”

Why it worked with climate change

Jamieson attributes the success in communicating the climate-change message to more Americans — Gallup finds nearly 70% agreement that human activity is causing temperature rise — to three factors:

“The evidence has become clearer. The communication has become more effective. And people have experienced events in their lives that they attribute to climate change,” she said. “That suggests this isn’t a hopeless task.”

Jon A. Krosnick, director of the Political Psychology Research at Stanford University, is not so sure. In his own surveys, conducted with the think tank Resources for the Future, public acceptance of climate-change science, though high, has not changed in years. What’s changed is that more people say they know something about the issue and have become more sure of their opinions.

And according to decades of psychology research, people who are paying close attention to a topic can be harder to persuade, he said.

Intelligence has little to do with it. People may cling to an unscientific view because it is tied up with their very identity, leading them to dismiss contrary evidence.

For years, the medical establishment held on to the idea that ulcers and stomach inflammation were caused by stress, rejecting a theory from two Australian scientists that a type of bacterium was the culprit. One even drank a culture of the bacterium, soon suffering the telltale symptoms. In 2005, they won the Nobel Prize.

Even if persuasion seems unlikely, the stakes are too high to quit, Jamieson said. Working with Bruce W. Hardy, a Temple University assistant professor of communication, she has developed four commonsense best practices for persuading those who reject science:

Leveraging. Cite credible sources that the audience trusts. Climate-change information from NASA, for example, might carry weight with an older Republican listener because of the agency’s success in the space race, she said.

Involving. Invite the audience to look at the data, rather than simply expecting them to accept conclusions at face value.

Visualizing. Use computer animations to portray a trend — say, a map showing the loss of sea ice.

Using analogies. Just as a recent slide in the stock market does not negate the market’s historic climb, one cold spell, for instance, does not negate the fact of global warming.

The real Sputnik

In 1958, a famous Life magazine cover blared “Crisis in Education,” with side-by-side photos of the archetypal easygoing U.S. teenager and his grim-faced Russian counterpart. As the American enjoyed extracurricular activities, the Russian studied physics, chemistry, astronomy, machinery, and something called “electrical technique” six days a week.

“It was a sham,” said Matthew Hersch, a Harvard University science historian who specializes in the Cold War era.

In fact, the United States was well ahead of the Russians in many respects, and the schools were fine. Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy both had misgivings about the cost of a space race.

Yet amid congressional and public pressure, Eisenhower signed a law establishing NASA. The Advanced Placement curriculum was created in high schools. Congress would eventually spend $250 billion in today’s dollars on Project Apollo, landing men on the moon in 1969. Science was king.

Could COVID-19 inspire that kind of support? Hersch has his doubts. The space race was viewed through the lens of freedom vs. communism: a matter of national security and pride.

» READ MORE: A guide to making sense of coronavirus studies

These days, the division is internal. Science is increasingly politicized, where even the motives of a pioneering researcher such as Fauci are called into question. Effective public-health communication depends on clear, uniform messaging, yet too often, Americans get the opposite.

The Trump factor

President Trump has called for less COVID-19 testing, when global authorities insist that more is needed. He has been dismissive of masks. Without any evidence, he claimed that one potential treatment was being delayed by people at the Food and Drug Administration who didn’t want him to be reelected Nov. 3.

Trump has vowed that a vaccine will be produced “before the end of the year, or maybe even sooner.”

Everyone wants a vaccine quickly — if it is safe and effective. But vaccines normally are tested for years, and even optimistic scientists say 2021 is a likelier timetable. The Trump administration has told states to be ready for distributing a vaccine by Nov. 1 — two days before the election.

The rush, critics warn, may only fan the flames of another kind of science doubt in the United States: distrust of vaccines. And if the rushed vaccines don’t work, or worse yet, prove harmful, public confidence in the most successful medical intervention in human history could be at risk.

Instead of a Sputnik moment, that would be a crash landing.