Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine has been fully approved by the FDA. What does that mean for the pandemic?

One change is that Pfizer can now market the vaccine, which is not allowed for drugs that are authorized only in an emergency.

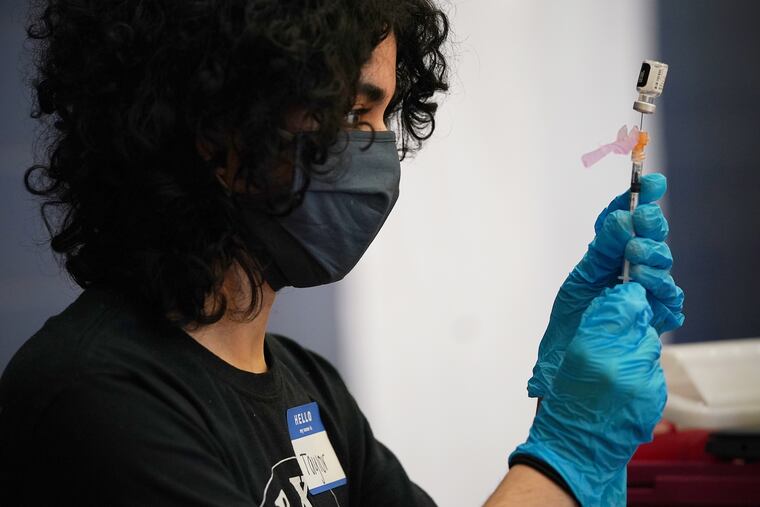

The Food and Drug Administration granted full approval Monday for the COVID-19 vaccine made by Pfizer Inc. and BioNTech SE, prompting public-health experts to hope that more people will sign up for the shots — whether on their own initiative or in response to new vaccine mandates.

The agency’s move, which allows the drug makers to market the vaccine for use in ages 16 and up, comes as hospitalizations are rising in much of the country and the contagious delta variant has prompted a new round of precautions.

Here is a breakdown of what the FDA action means, and why it might spur more use of the vaccine:

What is meant by full approval?

In December, the FDA authorized the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine for emergency use, meaning it could be administered only so long as an emergency remained in place.

The approval on Monday, on the other hand, remains in effect indefinitely, barring any evidence that the vaccine is unsafe.

The formal term for the agency’s action is approval of a “biologics license application.”

» READ MORE: Medical exemptions for COVID-19 vaccines, explained

According to the federal statute, that means the agency has found “substantial evidence” of the vaccine’s efficacy through “adequate and well-controlled investigations.”

The approval enables the vaccine makers to market the product, which is not allowed for drugs that are authorized only in an emergency. Following a long tradition of odd-sounding pharmaceutical brand names, the vaccine’s official moniker, Comirnaty, drew a mixture of puzzlement and scorn Monday on social media.

How much more evidence was involved?

Back in December, infectious-disease specialists generally agreed that the FDA already had substantial evidence that the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine prevented most cases of COVID-19, based on a clinical trial with more than 40,000 volunteers.

At that point, the agency also had determined the vaccines were safe, having looked for any signs of complications for two months after the second of two doses.

What’s new is that the agency now has reviewed this type of safety data for an additional four months in those original volunteers, and has found no cause for concern. The agency also has reviewed any reports of adverse reactions in the millions who got the vaccines in the “real world,” finding that the risk of side effects is far outweighed by the benefit of preventing COVID-19.

With its action Monday, the FDA also affirmed its confidence in the manufacturing process for the vaccine, having conducted extensive reviews of production lines.

The move drew wide praise from physicians such as Donald M. Yealy, chief medical officer at UPMC in Pittsburgh. In a news briefing Monday, he acknowledged that when compared with the approval for other drugs, approval for the vaccine may seem swift. But technology for this vaccine — and for the two others still authorized for emergency use — is based on decades of research, he said. (The mRNA platform used in the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, for example, is based on University of Pennsylvania research dating to 2005.)

“Nothing about this has been rushed. We have reams of data,” Yealy said. “These are some of the most-studied interventions that I’ve ever seen in 35 years of being a physician.”

Why more people might get vaccinated

In surveys of the unvaccinated, some have said that FDA approval would prompt them to sign up for the injections, but it is unclear how many will follow suit.

A bigger motivating factor may be the implementation of additional vaccine mandates by employers and universities.

So far, courts generally have ruled that the emergency authorization was legally sufficient for an institution to require vaccination. With full FDA approval generally interpreted as providing an even firmer legal basis, more mandates are now expected.

On Monday, for example, Gov. Phil Murphy announced that New Jersey teachers and state employees have to be vaccinated against the coronavirus. Any who are exempt will be tested once or twice a week, he said. The New York City school system also announced a vaccine mandate Monday.

Some institutions had instituted policies in anticipation of the FDA move. At Rowan University, students were allowed to request an exemption for “personal” reasons, but only so long as the emergency authorization remained in place. With full FDA approval, that type of exemption is no longer allowed, though students may still request an exemption for medical or religious reasons.

What the approval means for children

When a drug is fully approved, physicians are allowed to prescribe it for indications other than what is spelled out on the drug label — a practice known as “off-label” usage — as guided by their medical judgment.

In theory, the FDA’s move on Monday means that doctors can now administer the vaccine to children under 12. But pediatricians’ groups have cautioned against that practice, noting that the drug is still undergoing tests in younger children at smaller doses than what adolescents and adults receive.

What’s more, the legal basis for off-label usage in this case is somewhat murky, said Barbara Binzak Blumenfeld, an attorney in the FDA and biotech group in the Washington office of Buchanan Ingersoll & Rooney.

That’s because the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is approved for one age group, 16 and up, but remains under the emergency-use designation for another, children aged 12 to 15. Off-label usage is permitted only for drugs with full approval, not for those that are authorized for emergency use, yet the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine fits both of those descriptions.

“The way FDA worded the final label, I think it leaves it unclear as to whether that leeway for doctors to prescribe off-label exists,” she said.

Medically, it makes sense to wait until studies in younger children are completed, said Robert Bonner Jr., the medical director of the pediatric and ambulatory care center at Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia.

“We have to really wait for the trials to happen for children and get a sense of what dose is effective,” he said.

Swathi Gowtham, a pediatric infectious-diseases specialist with the Geisinger health system, agreed. If a physician were to administer a dose that was too small, the child might not be protected against COVID-19. If the dose were too large in relation to the child’s body size, that could lead to unforeseen side effects, said Gowtham, an immunization specialist for the Pennsylvania chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In the meantime, parents who are eager to protect their children have another option, she said:

“Parents themselves should get vaccinated.”

Staff writer Sarah Gantz contributed to this article.