Should the Pennsylvania primary be all vote-by-mail because of the coronavirus? Elections officials are divided.

Elections workers would have to suddenly conduct an entirely new type of election, and voters would have to know what’s going on and be willing to vote by mail.

Absentee ballots don’t require in-person contact with other people. Perfect for a public health crisis.

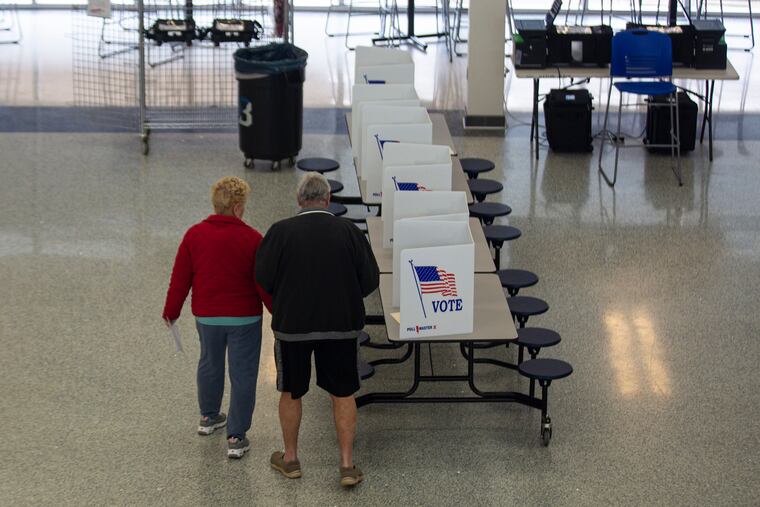

But should every Pennsylvania voter be required to cast a ballot by mail — with no polling places, no voting machines, and no election day as the state has known it?

Maybe, some elections officials and voting rights advocates say.

Not because they want to, or as a matter of voting reform, but because they say running a normal election is all but impossible during the coronavirus pandemic. In addition to postponing the primary election currently scheduled for April 28, they say, that time should be used to prepare for an election done entirely by mail.

“I believe it should be pushed back a month and do an all mail-in,” said Deborah Olivieri, elections director in Berks County.

“Postpone this thing and run the whole thing by mail-in ballot,” said Forrest K. Lehman, elections director in Lycoming County.

“What makes the most sense right now, given the situation we all find ourselves in, is to at a minimum move the date, right?" said Lee Soltysiak, Montgomery County’s chief operating officer and clerk of its elections board. "And No. 2, frankly, consider seriously whether the election should be an all-mail-in election.”

Gov. Tom Wolf has said state officials are considering whether to move the date of the primary election, and county elections officials are pleading with the state to do so. It’s unclear whether the governor has the power to unilaterally make such a decision.

Moving to a universal vote-by-mail system, though, would be an even more difficult move, both logistically and culturally, and the idea has elections administrators and activists divided. It’s a massive change, they say, and doing it in one fell swoop leaves no room for error. Elections workers would have to suddenly conduct an entirely new type of election, and voters would have to know what’s going on and be willing to vote by mail.

“The all-mail election, to me, is the nuclear option,” said Jeffrey W. Greenburg, elections director in Mercer County. “Could we do it? I don’t know, maybe.”

One reason voting entirely by mail seems like a solution is that Pennsylvania has already made dramatic changes to absentee voting.

» READ MORE: Evictions, student loans, PSSAs, and more: What Pa. lawmakers are proposing in response to the coronavirus

After years of restricting absentee ballots to only those voters who were unable to cast votes in person, the state last year enacted a law allowing any voter to vote by mail without needing to provide a reason.

That already had elections administrators worried, because they had to implement new rules and prepare for something neither they nor their voters had seen before. How many ballots should they print? How many envelopes should they buy?

If the answer, suddenly, is to prepare enough for every voter in the state, counties will need to buy a lot of new materials, along with machines to open the envelopes and scanners to read the ballots.

They’ll also need to make sure that people don’t vote twice, that signatures match what’s on file, that votes are tallied on time, and that ballots are kept secure.

“Going to all-mail voting is not flipping a switch. It is a very complex administrative, technological change,” said David J. Becker, head of the Center for Election Innovation and Research in Washington. “And in places where it’s been successful, that success has come after years of working with elections officials between the state and county level, building processes, buying proper technology, and, very important, educating and acculturating the electorate to mail-in voting.”

Some states, including Colorado and Oregon, conduct elections entirely by mail, and others, including Arizona, are moving in that direction. But even if the logistical challenges could be solved — such as Congress or the state legislature in Harrisburg allocating emergency election funding — the issue is voters and voting culture, Becker said.

Not a single election has been conducted under Pennsylvania’s new rules. Under the more restrictive old rules, only about 5% percent of ballots cast were absentee. Under the new system, elections officials had predicted an initial jump to between 15% and 25%.

That’s a long way from 100%.

» READ MORE: A special election in Bucks County won’t be delayed because of coronavirus, judge rules

“There is a very, very strong culture that people go vote in person at their precinct on Election Day. That is where the vast majority of people vote,” Becker said. “This could have an effect on the makeup of the electorate, this could have an effect on turnout, and even if it doesn’t, it certainly could have an effect on a voter’s ability to have a ballot counted.”

Voting rights advocates have also expressed concern over the disproportionate impact of a move to vote-by-mail. Becker’s research has shown that racial and ethnic minorities tend to vote in person at higher rates than white voters.

Put all those concerns together and “you’re going to end up really regretting it” if Pennsylvania moves immediately to an entirely vote-by-mail model, Becker said.

Plus, in some counties, new voting machines are set to be used for the first time in the April 28 primary. If those machines are used for the first time in November, with its much larger turnout, the potential is high for confusion, long lines, and even disenfranchisement for some voters.

“We’re not going to have any chance to work out kinks before what will truly be a monumental election for this country and for the state,” said Delaware County Councilwoman Christine Reuther. “To not have machines that we have a dry run with is frightening.”