Philly Fighting COVID partnership was ‘a mistake,’ health commissioner says, as Mayor Kenney calls for new vaccination clinics

“I am disappointed by what has transpired with the organization Philly Fighting COVID,” Mayor Jim Kenney wrote in a letter to Health Commissioner Thomas Farley.

Mayor Jim Kenney on Friday urged city health officials to swiftly open coronavirus vaccination clinics to replace the one run by Philly Fighting COVID and ensure the 7,000 people vaccinated at the now-shuttered site will receive their second doses.

In a letter, Kenney also directed the health department to investigate “how PFC came to work with” the city on testing and vaccination and provide a report within 30 days. He wrote that he was confident in Health Commissioner Thomas Farley’s handling of the pandemic, but concerned the debacle with the group could “cast a shadow” on the city’s vaccine distribution.

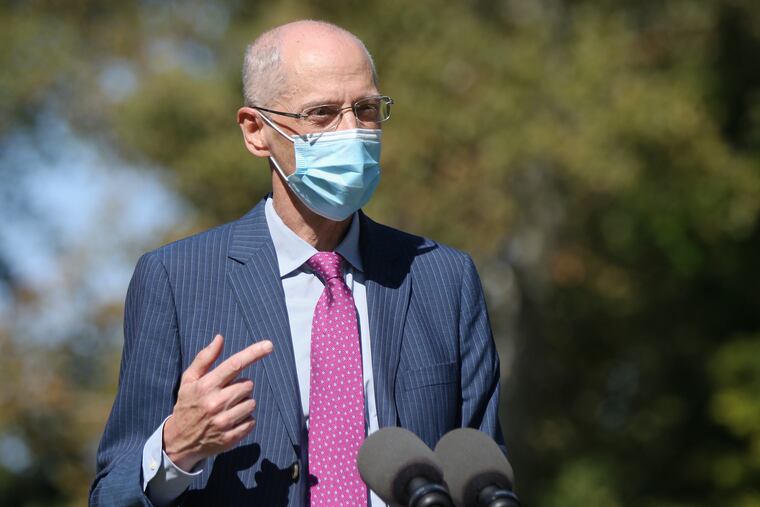

Farley told The Inquirer on Friday it had been “a mistake” to work with Philly Fighting COVID, which is run by a self-described bunch of college kids and was dropped as a city partner on Monday after questions emerged about its for-profit status and potential use of patient data.

“We shouldn’t have gone into relationship with them in the first place,” Farley said.

He said he had realized the group was “untrustworthy” after it updated its privacy policies to allow residents’ personal information to be sold.

» READ MORE: City drops Philly Fighting COVID as vaccination partner after it failed to disclose for-profit arm

Andrei Doroshin, the group’s 22-year-old CEO, has insisted the wording of the updated privacy policy was a mistake and that he never intended to sell anyone’s data. On Thursday, he also admitted he had taken four vaccine doses home and administered them to his friends.

But in a news conference inside his Fishtown apartment complex on Friday, Doroshin maintained that he and his organization had done nothing wrong, instead slamming Farley and claiming he and his Drexel University friends were “the only ones who had a plan” for vaccine distribution.

The saga has increased tension in the city amid the high-stakes vaccine rollout — one that has already been slowed nationwide by the extremely limited federal supply of shots, which is millions short of what’s needed. Since older and high-risk residents became eligible for the vaccine earlier this month, people have clamored for appointments, and often found them hard to get.

Meanwhile, city officials have asked residents to stay on high alert and heed requirements for masking and distancing. In his letter, a copy of which was obtained by The Inquirer, Kenney told Farley his approach to the nearly year-long pandemic has “helped save thousands of lives.”

The mayor also ordered the department to send all doses allocated to Philly Fighting COVID — which had been about 6% of the city’s supply, he noted — to other vaccination sites.

He specifically directed the department to increase the vaccine allotment for the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, another organization that is vaccinating residents and one cited this week by council members who questioned whether systemic racism had played a role in the city’s partnership decisions.

Farley said he agreed with those and other requests outlined in Kenney’s letter. “It’s an appropriate way to really learn from this and improve,” Farley said.

On Friday, City Councilmember Bobby Henon’s office confirmed that Philly Fighting COVID had provided coronavirus tests to his family at his home in December. The report of private testing for Henon’s family, first reported by WHYY, came after Henon defended the group this week.

Asked about testing for the councilmember’s family, Doroshin said “there were no favors done” and said his group had provided at-home testing to many residents — it was not clear how many — but not to any other city officials. A spokesperson for Henon said workers at the site had offered to come to the family’s home after they showed up when it was closed and said the family had paid in full for the testing.

Testing had been Philly Fighting COVID’s first role in its partnership with the city; Philadelphia gave the group a $194,000 contract for coronavirus testing last summer, according to documents Doroshin provided to The Inquirer. The city has failed thus far to release documents related to the partnership, despite a request from The Inquirer under the state’s Right to Know law. A city spokesperson did, however, acknowledge that the health department had authorized more than $110,000 for testing services.

The city did not give the group any funding for vaccinations, the spokesperson said.

At the start of the vaccine rollout, Philly Fighting COVID operated the only preregistration website in the city, and officials encouraged Philadelphians to use it. City logos were plastered throughout the group’s mass vaccination center at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, leading some to assume the site was run by the city.

The city now has its own preregistration portal, where residents sign up to be notified when appointments are available.

Beyond the questions about its privacy policies, the group had also drawn scrutiny for establishing a for-profit arm despite presenting itself as a nonprofit. Farley said he had been alerted to the potential issues by questions from an Inquirer reporter.

“That was unprofessional and that made them an untrustworthy organization,” Farley said. “Absolutely, I think it was right to terminate that relationship.”

Doroshin insisted Friday that “Philadelphia’s dirty power politics” contributed to the city’s decision to cut ties with his organization, but he did not elaborate when pressed by reporters.

He said the organization plans to provide the city’s health department with all the data it collected from residents, then delete the data from its servers.

Some city leaders have openly worried that the group’s alleged missteps could further existing mistrust, particularly among people of color, who are already hesitant to get a vaccine after decades of health-care inequity.

“We need to work to earn back that trust,” Farley said Friday.

Among other requests, Kenney asked the health department to “identify any and all weaknesses in the vetting process that could have prevented the present outcome” and include proposals in its report for ensuring the city’s future vaccine partners act equitably and professionally.

“I look forward to reviewing the findings of your report,” he wrote to Farley, “and to seeing every Philadelphian access these life-saving vaccines.”

Staff writer Laura McCrystal contributed to this article.