Joblessness is rising far more slowly in Europe than in the U.S. during pandemic, new figures show

European unemployment crept up only modestly since the start of the coronavirus lockdowns, data released Thursday showed, at a time when millions of Americans filed for benefits.

BRUSSELS — European unemployment crept up only modestly since the start of the coronavirus lockdowns, data released Thursday showed, at a time when millions of Americans filed for unemployment benefits.

The contrast showed the effect of Europe's starkly different approach to fighting the economy-busting effects of the pandemic, with many governments directly intervening to subsidize private-sector salaries. In the United States, stimulus and relief programs have been comparable in scale, but not as directly tied to avoiding layoffs.

Most of the data released Thursday by many European countries was for March, meaning it reflects about two to three weeks of the pandemic shutdowns, but not the full scale of an economic cataclysm that has only escalated since then. The figures reflect a significant shock to the system at a moment when policymakers are warning of a recession this year larger than that during the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

Still, when compared with the U.S. jobs carnage for the same time period, when jobless claims spiked to record levels in the United States during the first weeks of widespread lockdowns, the European figures appear far more contained. Seasonally adjusted unemployment across the European Union rose by 0.1 percentage point in March, to 6.6%, according to the E.U. statistics agency.

The overall economic picture is grim in the European Union, with the economy shrinking by 3.5% in the first quarter of the year, the sharpest decline on record, according to figures also released Thursday. The U.S. economy contracted 4.8% during the same period.

The jobless figures have been cushioned by vast numbers of European businesses that have signed up for subsidy programs in which governments pay up to 87% of workers' salaries to avoid layoffs. The system, pioneered in Germany during the 2008-2009 global recession, has now been imitated widely in Europe. The thinking among many policymakers is that the economic blow of the pandemic can be softened if workers are able to keep paying their bills and if businesses do not have to hire and train an entire new set of employees as the crisis abates and ordinary economic life resumes.

"If you have 10% of the workforce getting laid off and going on unemployment benefits, then you would have 10% of the current high-spending consumers who wouldn't be spending anything because of the insecurity of the future," said Danish Employment Minister Peter Hummelgaard. His government has presided over a program in which it pays 75% of workers' salaries, up to $3,355 a month, for employers whose revenues have taken a significant hit from the lockdown. Employers cover the other quarter.

» READ MORE: Pa. officials fielding 20,000 calls a week as deluge of applicants crashes unemployment system

In Denmark, the unemployment rate rose to 4.2% in March, up from 4.0% in February, according to figures released Thursday. The figure would have been far worse if the 150,000 Danish workers who have been enrolled in the salary subsidy program had instead been laid off, Hummelgaard said in an interview.

If those workers had joined the jobless rolls, Denmark's unemployment rate would have jumped to roughly 9.5%.

"Businesses are encouraged and obliged to keep workers in their current jobs, for the sake of the individual worker, obviously, but also for the overall sake of the economy and our ability to get back on track fast," Hummelgaard said. And as Denmark starts to reopen its society, he said, policymakers are already looking at more traditional stimulus programs and hope to wind down the subsidy program by early July.

The costs of the programs can be difficult to estimate as they get underway, since most governments have made them open to any eligible company rather than capping them at a certain level of funding, and the economic outlook continues to darken. The official British Office for Budget Responsibility estimated this month that Britain's program, which is subsidizing up to 80% of the salaries of eligible workers, would cost about $65 billion over three months — a share of the British economy equivalent to a program that would cost $508 billion in the United States. The British program has since been extended by a month, until the end of June. Employers are clamoring for it to stretch until the fall.

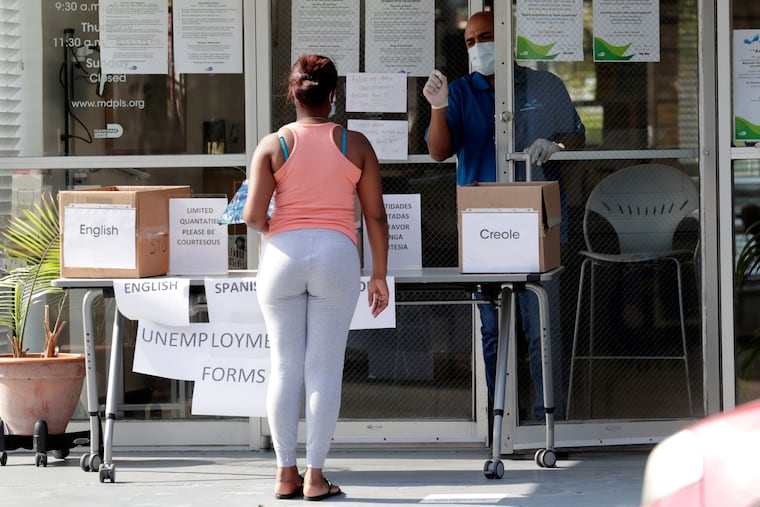

The U.S. small-business loan initiative known as the Paycheck Protection Program contains elements similar to the European efforts, since it fully forgives loans if they are used for payroll, rent or mortgage payments. Congress has channeled $659 billion toward it so far. But its funds do not go exclusively toward avoiding layoffs, and U.S. unemployment filings continued to skyrocket Thursday, bringing total new claims to 30 million in the last six weeks.

Europeans say the programs make a major difference in the way they plan their lives.

"It's definitely keeping our jobs alive for the moment," said Maria Hoejer Romme, a Danish business researcher whose company enrolled in the program last month.

She and her husband have a 10-month-old baby and just bought a new home, making them vulnerable to sudden economic disruptions, she said. They recently had a conversation about what would happen if she were laid off, something she said she never could have imagined just a few months ago. The salary subsidy program has made her company more resilient and helped her family plan for the strange new pandemic-struck world.

"There might be a chance I'd lose my job, but now I can think, 'Okay, it probably won't happen,'" she said. "You can adjust your economy, and you can look into the future."

The programs have been rolled out in Europe's largest economies, including Britain, France, Germany and Italy, and have quickly expanded to cover major portions of the workforce. Nearly half of French workers are enrolled; in Britain, two-thirds of employers are participating. The German federal employment agency announced Thursday that employers enrolled up to 10.1 million workers in its wage subsidy program between mid-March and April 26, more than triple the total for all of 2009.

The impact of the pandemic in terms of lost work hours is similar on both side of the Atlantic, said Holger Schmieding, chief economist for the Hamburg-based Berenberg Bank. But while in the United States the "eye-popping numbers" show up in unemployment figures, in Europe they show up in on-the-job benefits, he said. The European system saves "a lot of anguish in hiring and firing."

Most of the programs were initially set up to last only three months, although many have now been extended into the summer. Policymakers hope that as lockdowns ease, governments can dial back the subsidies. If they cut off the programs suddenly, they could still face a wave of layoffs, only this time with depleted coffers. France, for instance, plans to pare back the program after June 1.

Unemployment is still rising across Europe, despite the programs — just at a slower pace than in the United States. German unemployment in April rose 0.7% percentage points to 5.8% and is forecast to rise further.

» FAQ: Your coronavirus questions, answered.

The United States will release unemployment figures for April on May 8. Analysts estimate that the U.S. jobless rate is currently between 10 and 15%, up from the 50-year low of 3.5% in February, before the pandemic hit.

"The corona pandemic is likely to lead to the worst postwar recession in Germany. As a result, the job market is also under considerable pressure," Detlef Scheele, head of the German Federal Employment Agency, told reporters Thursday. German policymakers agreed last week to increase the salary subsidies so that they cover up to 87% of a worker's pay, up from 67% previously.

Economists say wage subsidy programs typically work most effectively if the worst economic crisis is relatively short — just a few months, ideally — since companies will have a much harder time recovering if they are frozen much longer than that. Customers will move on; demand will change. Assuming lockdowns can be eased relatively quickly, the programs may prove successful, but if the health situation deteriorates again and forces economies to hibernate until fall, the outcome may be less rosy.

"If we see a longer economic downturn in Europe, we'll see the same problems as the U.S. They will have just delayed it," said Simon Tilford, director of research at Forum New Economy, a Berlin-based economics think tank. "It's not a long-term solution to a sharp reduction in demand for labor, because the state cannot afford to subsidize wages at that level indefinitely, and it would slow the pace of adjustment."

Still, in the short run, many European employers see the wage subsidy programs as a godsend.

"Small businesses have no extra money to cover a crisis situation," said Paul Konradi, 33, general manager of Rowdy, a chain of four hip barbershops in Berlin and Hamburg. Customers used to come for haircuts, hot towels and beard trims in establishments decked out with exposed brickwork and vintage chrome and leather chairs. Now those clients are gone.

Without Germany's subsidy program, Konradi said, he probably would have been forced to start laying off some of the company's 26 employees. "There would be no money" without the program, he said. "I don't know what I'd do."

In France, Labor Minister Muriel Pénicaud said Wednesday that 11.3 million workers were now enrolled in her country's program, which pays up to 70% of salaries.

"I think we can be proud in France that we have put in place this massive safety net," she said.

The programs are "effective, but it's not absolute," said Jean Pisani-Ferry, a French economist and nonresident fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economists who has taken part in crisis consultations with the French government.

Still, as a gamble in risky times, he said the programs make sense.

"You have two risks. You have the risk of keeping companies afloat that have no future" by using wage subsidy programs. Or, without the programs, "you have the risk of precipitating the collapse of companies that do have a future," he said.

___

The Washington Post’s Loveday Morris in Berlin, Christine Spolar in London, James McAuley in Paris and Quentin Ariès in Brussels contributed to this report.