Strange as it seems, a recent study found that people with dementia performed better on cognitive tests after wearing helmets that emitted near-infrared light twice a day for six minutes.

Some also slept better, and their caregivers reported that patients had more energy and were less anxious.

The research was conducted by a team that included Marvin Berman, who has a Ph.D. in educational and organizational psychology and works in Elkins Park, and was led by Jason Huang, a neurosurgeon at Baylor Scott and White Health in Temple, Texas. It was published in February in the journal Aging and Disease.

Huang, who was principal investigator, said he was “pleasantly surprised” by the results and found them “quite encouraging.”

Two experts on dementia from the Philadelphia area — Jason Karlawish, who is co-director of the Penn Memory Center, and David Weisman, a neurologist who directs the Clinical Trial Center at Abington Neurological Associates — said the study needs to be followed up with a larger, multi-site trial that more clearly categorizes types of dementia.

Huang said he is seeking federal funding for future work. He plans to add data from another 40 patients that Berman recruited and reanalyze the results. That information was not available in time for the journal’s deadline, he said. He also wants to study how changing light doses affects results.

Berman, who had previously studied neurofeedback — training people to control brain activity — in patients with dementia, learned about a test of infrared treatment by British doctor Gordon Dougal from the wealthy husband of a client. Berman said he was skeptical, but the client wanted to try the device. His wife’s symptoms improved.

Huang’s interest in infrared grew from being a combat surgeon in Iraq, where he treated many soldiers with brain injuries. That work continued when he moved to Texas and saw numerous soldiers with continuing cognitive problems and dementia. He met Berman at a Department of Defense meeting, and their collaboration ensued.

According to clinicaltrials,gov, the government list of clinical trials, studies testing near-infrared light for dementia are also being directed by Unity Health Toronto, University of Florida and University of California, San Francisco.

The published study included 57 patients with mild to moderate dementia. The researchers did not attempt to include only patients with a certain type of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Some had brain injuries in the past. Two-thirds received the light treatments, and the remaining one-third received a sham treatment.

Despite the “red” in its name, near-infrared light is invisible, so patients and their caregivers could not see the light from the helmet. Patients used the helmets at home.

After treatment, their scores on the 30-question mini-mental state exam (MMSE) improved by 4.8 points while those in the sham group rose by 1.4 points. Scores also rose significantly for a logical memory test and for auditory verbal learning tests.

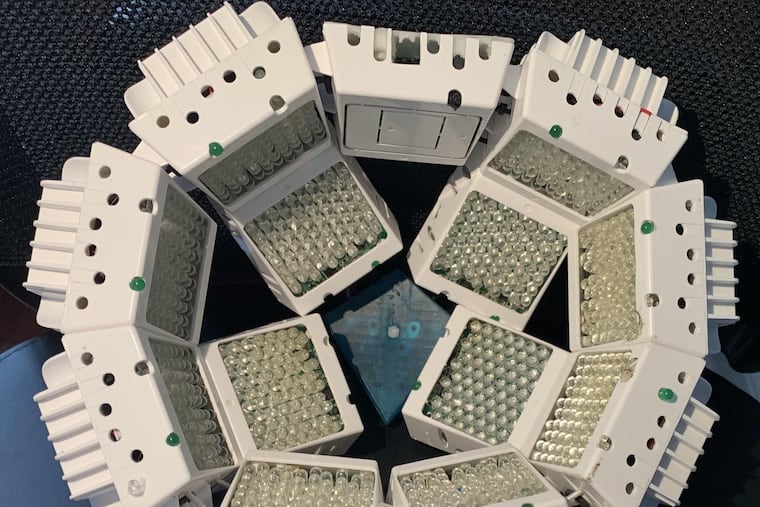

The changes in cognition and mood were noticeable enough, Huang said, that caregivers wanted to continue using the helmets, which were produced by Dougal and are not commercially available. Patients can access them at Berman’s Quietmind Foundation practice, but must pay an “equipment fee” of $2,995 to $10,000 and enroll in a two-year clinical trial.

Both Huang and Berman said they had no financial interest in a company that makes infrared helmets.

Why would infrared light affect dementia?

Huang said he wishes this was as simple as having a drug that targets a specific protein and cures a disease. But that pharmaceutical approach has so far not worked well against dementia.

Berman said the light is believed to stimulate production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), an energy-carrying molecule that is often depleted in neurological conditions. Specific infrared light wavelengths also have anti-inflammatory properties that can improve blood flow to the brain. All of those changes could affect thinking ability and general brain health, he said.

Huang and Berman both said patient performance declined when the treatments stopped.