How working Christmas Eve in the hospital became this family’s tradition

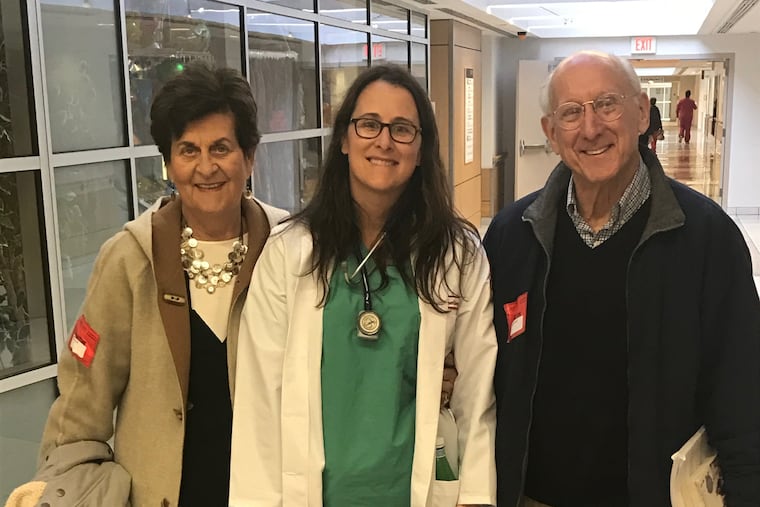

Every year, my parents come to the hospital on Christmas Eve for a few brief minutes that impact us all.

In December 2013 I had been a doctor for five months. I was an intern in Emergency Medicine at Temple University Hospital and my parents agreed to come to Philadelphia for dinner between my shifts on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. My father is a doctor and was raised as an Orthodox Jew; most of his life, and mine, he worked the Christmas holiday so that doctors who celebrate could have time off with their families. I decided I would do the same.

On Dec. 24, I planned to pick them up at 30th Street Station after I finished my 7 a.m.-to-3 p.m. shift. Shortly before 2 p.m., an elderly woman carrying holiday shopping bags tripped as she was walking up the steps to her daughter’s house, cutting her forehead on the nearby metal railing. Fortunately, a CT scan showed no internal injury and I could stitch closed the wound and get her home in time for dinner.

By the time I finished it would be well past 3 p.m. I called my parents to say I’d be at the station as soon as I could and gathered my tools to close the grandmother’s wound. Her entire family had gathered around their beloved matriarch, and I felt nervous to work before an audience so early in my training. It turned out to be a cheerful and supportive crowd.

“Looks great, doc,” one family member observed as I finished the first section. “Oh, that looks really good,” said another. I was halfway done when my colleague Ashley poked his head in.

“Can I talk to you for a second?”

I stepped out.

“Your parents…”

“Yes?” I said anxiously.

“They’re here.”

“What? Where?”

“Here.”

“Where?”

“Here.”

There was my mom, radiant in her red coat, smiling. In our emergency department. Who let them in? I thought frantically. “He said he’s a surgeon,” Ashley said. Well, of course he’s a surgeon. But he’s not a surgeon here.

I’m not sure if I can explain what it feels like to be fresh out of medical school and unexpectedly find your parents – a surgeon and a nurse – on your ward. I said a quick hello. “I need to finish putting in these stitches and sign out and then we can go.” I walked back to Bed 13. My father was following me. He loves medicine. And he was ready to join so we could put in the stitches. “Dad,” I said. "You can’t come.”

As a first-year medical student in 1960, my father would go to the emergency department at Johns Hopkins Hospital on Friday nights as a “break” from his studies. If he was lucky, the tired doctor on call would show him how to suture a cut or set a bone. He would later train under the legendary surgeons of Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, and became the National Cancer Institute’s youngest-ever chief of surgery. He is a pioneer in using the body’s own immune system to treat, and often cure, the once-deadly cancers of hundreds of desperate patients.

He is not a man who frequently hears, or accepts, the word no. But he did, reluctantly, heed my words and was led to a suitable place to wait.

And so that first Christmas Eve began an annual tradition. I would never again attempt to get my parents at the train station. They come to the hospital on Christmas Eve for a few brief minutes that impact us all.

Three years later, it is 2016. I have finished my residency training and am now an attending physician at Temple. Supervising others instead of being supervised. What never changes is the strange feeling of the hospital on Christmas Eve, the almost palpable loneliness of some who have nowhere else to be, alongside those who are critically ill and wish they could be anywhere else. I greet my parents but still have more to do. As I take them to a waiting room, a nurse comes out of Room 24. “Dr. Rosenberg?”

“Yes?” my father says. I too am looking at him.

The nurse is confused. “Um … the other Dr. Rosenberg.”

The nurse is talking to me. Somehow, I am Dr. Rosenberg.

“Yes?” I respond.

“Should we give the patient the second liter of fluid now?”

“Yes, please,” I say.

Before I can leave, I go back to the desk to find the doctor working the next shift so we can discuss and transition the patients. As we finish, he has a question.

“Is your father in town?”

“Yes,” I say cautiously. “Why?”

He smiles. “Because there is a man 20 feet away who, based on the way he is looking at you, could only be the most proud father of a young doctor.”

There he was. He had sneaked out of the family room. He’s standing in the hallway watching me give report. He can’t hear the words I am saying, but of course he recognizes the ritual. He is there. He is beaming.

I pretend to be embarrassed.

Next, and last for now, it is Christmas Eve 2017 at 2 p.m. A man collapses while singing at church. In minutes, he is in our emergency department.

We work frantically to get him to a lifesaving cardiac procedure. I call his son who, like me, is at work. I am moved by the way his coworkers carefully gather him up and bring him to the hospital. I learn that the son has recently lost his mother. I am so sorry to give him more bad news, but we cannot yet say if his father will recover.

I am bone-tired. Exhausted. I remember my parents are here and we will soon be at dinner. I wonder if I would be better off going home to bed. I greet them in the lounge, faking an enthusiasm I don't yet feel.

“So good to see you,” I say, hugging them both.

My dad looks at me carefully. “What happened?” he asks.

“Nothing,” I smile. “I’m good. Let’s go.”

He is my father. His blood is my blood, and he will not let me off the hook. He takes on the serious face familiar to his daughters, his colleagues, and his patients. It is a face of unflinching contact with reality.

“It’s a hard job, Naomi. (Pause) It can be a very (pause) hard (pause) job. We’re proud of you.”

I’m not sure there are words for how I feel, and the ones I find may fail me. Words to tell what it feels like to be the daughter of this father, to follow in the footsteps of a doctor who is larger than life and also life itself.

So I will say this: To anyone who becomes sick or injured at Christmas or at any other time, we are here. We will be gowned and gloved, we will be awake and ready, and we will be here, for you. Not just us but the generations of men and women who got us here. Those who came before us, in every emergency department, on every Christmas.

And one more thing. … See you Christmas Eve, Dad. I love you.

Naomi Rosenberg, M.D., is an emergency medicine physician at Temple University Hospital.

We go to dinner and all seems right

By Steven A. Rosenberg

For 44 of my 78 years I have been a surgeon at the National Cancer Institute. For the past five years my wife, Alice, and I have traveled to Philadelphia on Christmas Eve to visit our daughter, Naomi, now an attending physician in the emergency department at Temple University Hospital. We meet Naomi at the end of her shift and go to dinner together.

Watching the frenetic activity in the emergency department brings memories of a Christmas Eve at the Brigham Hospital in Boston when I was a surgical intern attempting to revive a young man killed by a car on the side of the road while he was helping to change a flat tire for people he did not know.

Then Naomi approaches and a sense of unreality momentarily swirls in my brain. I see the little girl whom I sang to sleep every night over 30 years ago, learning to take her first steps. But now she is walking briskly toward us in blue surgical scrubs, sometimes stained with blood. Naomi, Alice, and I hug. Naomi finishes transitioning her care to the next shift and charting the day’s patients. We then go to dinner and all seems right.

We are Jewish and every year we offer to work on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day to enable colleagues to be at home for a holiday that is a happy time but doesn’t have a special meaning for us. Hospitals have an eerie feeling at Christmas — emptier than usual with the staff somehow more connected to one another. The festive decorations contrast with the human suffering we see around us. There is a strange but warm feeling of solitude combined with pride to be a doctor standing watch while others celebrate with their families.

Then we go to dinner and talk mainly about medical things. The emergency department has a special meaning to us. Alice and I met in the first week of my internship. She was the head nurse in the emergency department, and we first spoke when there was a lull in activity at about 2 a.m. We married five years later.

We share stories about patients that touched us and laugh about the incongruous situations we experienced that, strangely, were both funny and sad at the same time.

We want to linger, but Alice and I take the train home early. We know our daughter needs her sleep. She will be back at the hospital at 6 a.m. on Christmas Day.

Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., is chief of the surgery branch at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.