I found out that my patient died — 6 months after the fact

What if I didn't happen to click on my patient's electronic chart? Blissfully ignorant, I might have assumed he was doing fine.

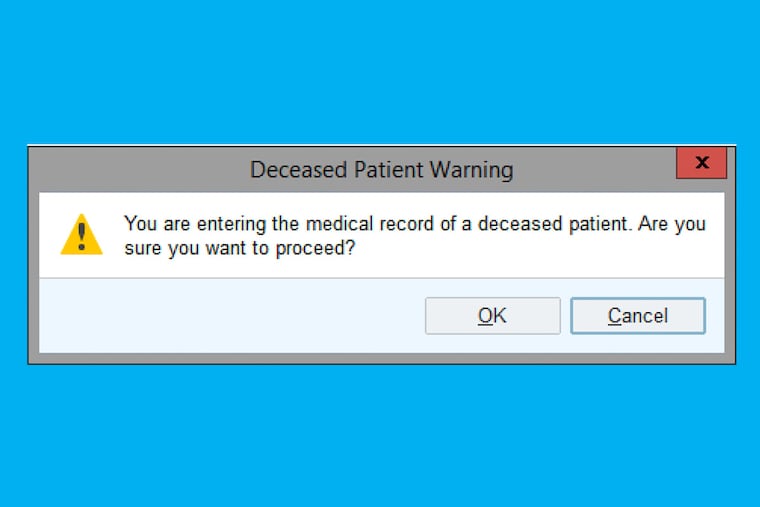

Recently, while following up on my list of patients, I clicked to open a chart, only to be greeted with a pop-up alert: “You are entering the medical record of a deceased patient. Are you sure you want to proceed?”

That hit me like a gut punch. My patient had died? When? How? Why wasn’t I told? Was there anything I could have done?

Of course I clicked to continue. Immediately I began to dig into the chart, desperate to know the full story. I reviewed clinical visits and discovered a pattern that suggested a rapid decline from metastatic cancer. He died six months before! The last time I had seen the patient was a year prior, and he had been doing well. My role in his care had indeed been important, even essential to identifying the cancer at first — I had recognized a skin sign of a possible underlying problem, and urged the primary team to work him up for cancer screening. Yet keeping his dermatologist informed as the treatments progressed was obviously not deemed important.

I think that all doctors should be notified when any patient whose care they have touched has passed away.

Even with more information from the chart, I was left unsatisfied and sad. I felt my duty to my patient was yet unfilled, but I was not certain what the right course of action should be. Further, I didn’t know if there was a way to prevent this from happening again. Though in this case, the patient got most of his care at one hospital and electronic medical record systems are becoming more interconnected, it’s hard enough to get clinical information when I request it, let alone when I don’t know anything’s wrong.

As a doctor, it’s important that I get follow-up information. I often plead with patients to let me know how they are doing. Naturally my tendency is to assume, self-flatteringly, if I don’t see someone again, that my treatment worked. But what if something went wrong? There’s nothing worse than seeing a patient years later, only to hear that my recommendations were ineffective, but I never knew and was powerless to rectify the problem.

Fortunately, in my general dermatology practice, deaths are uncommon events. Metastatic skin cancer has taken some patients’ lives. But otherwise, my patients’ skin diseases are not what has ended their lives.

I take pride in the fact that I regularly treat conditions that, while not life-threatening, are diseases that when addressed may restore my patients to fully engaging and participating in their lives unimpeded. My patients also represent a full spectrum of ages, not just elderly, so deaths are generally not expected. As an academic physician, however, I often see people with rare and complicated diseases that may predispose them to untimely ends.

When I learned this patient had died, one part of the pain was how easily I could have never found out. I take care of hundreds, even thousands of patients, and I’m simply not capable of keeping track of what happens to them all. I do my best to track the ones that are in the most obviously tenuous situations, but what if I hadn’t clicked on my patient’s chart? Blissfully ignorant, I might have assumed he was doing fine. My patients, even the ones I don’t know well, often feel like old friends. Honestly, there are many patients I see more frequently than the people I consider close friends. It’s these long-term relationships, getting to be an observer and participant in these lives that brings me some of the greatest joy as a doctor.

Aside from learning about what happened, did I have any further responsibility? Should I call the patient’s family? I’ve spoken with families after deaths, but typically it’s in the days and weeks immediately afterward, and usually it’s with a spouse or child I’ve known from their attending visits with the patient. But not over six months later.

I did not reach out to this patient’s family. I’m embarrassed to admit that my uncertainty over the correct action kept me from doing anything, which was the path of least resistance. I only ever met the patient himself and not any of his family members. Who knows if the phone number even worked? Should I send a card, and if so, to whom? I felt a need to express my condolences, and yet I wasn’t sure what would be meaningful for the family or what gesture would be wanted. Some families appreciate that sort of thing, but other people likely prefer to just move on, and I wouldn’t want to be expressing my condolences simply for my own benefit.

Though it is fortunately infrequent in my practice, I hope that I can provide closure and support to families of patients when they die. But I will only be able to do that if I know when that happens.

Jules Lipoff is an assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.