How school closings due to coronavirus are helping parents see benefits of later start times for teens | Expert Opinion

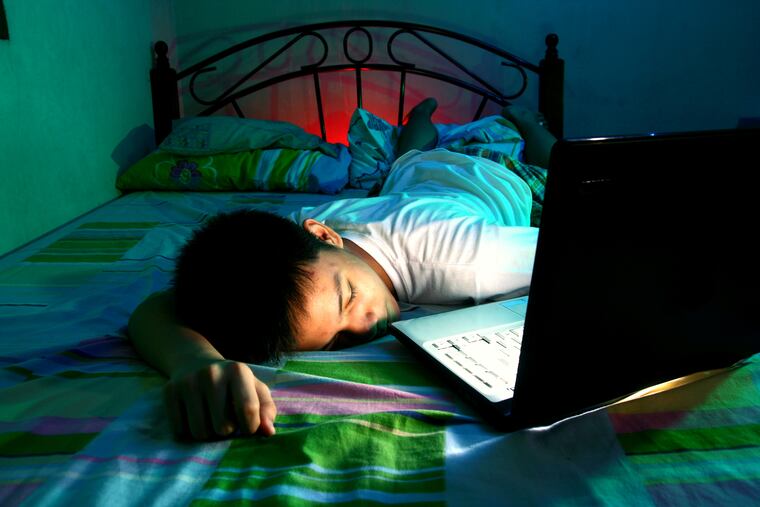

For many families, the school-from-home day starts later than a typical day and the lack of travel time to school has resulted in many teens gaining an hour or more of shut-eye in the morning.

Parents, have you noticed any positive changes in your teen since COVID-19 necessitated closed schools and distance learning? Have you noticed a more alert adolescent? A less anxious adolescent? An easier-to-get-along-with adolescent? Had you expected the opposite?

For many families, the school-from-home day starts later than a typical day, and the lack of travel time to school has resulted in many teens gaining an hour or more of shut-eye in the morning. If your teen is in a suspiciously better mood, it may be the result of your family’s unwitting participation in a real-time experiment of what happens when your teen is afforded the opportunity to sleep later on school mornings.

Scientific research has proven that internal circadian clocks change in adolescence and that a shift in melatonin production makes it very difficult for the average adolescent to fall asleep before 11 p.m. This fact, combined with overwhelming evidence that teens need eight to 10 hours of sleep a night, led both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine to issue sternly worded statements within the last decade urging that all middle and high schools start no earlier than 8:30 a.m.

Despite this, most middle and high schools continued to start before 8 a.m., a virtual guarantee that teens would not be able to sleep late enough in the morning to attain the recommended amount of sleep they required to function, learn, and thrive.

But the new normal of distance learning may have changed that, literally overnight.

I asked my colleague Meg Fisher, chair of pediatrics at Monmouth Medical Center, if she noticed a change over the last month in the teenager who lives in her home.

“He says he feels better when he gets up, and he seems more interested in school,” she said of her nephew, John Smith.

» HELP US REPORT: Are you a health care worker, medical provider, government worker, patient, frontline worker or other expert? We want to hear from you.

Fisher, like me, is a member of the Task Force on Adolescent Sleep and School Start Times for the New Jersey Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Smith, a junior at Shore Regional High School in West Long Branch, told me he used to have to get up at 6 a.m. because his school started at 7:30 a.m. Now, his “school day” starts at 8 a.m. and he awakens around 7:30 a.m.

“The extra hour and a half [of morning sleep] is a major factor” with regard to his morning alertness, he said, as well as the relief it affords him later in the day: “This has overall helped me focus better and have more energy to complete my homework later at night.”

These sentiments were echoed by the responders to a Facebook post I put up asking for parents of teens who were able to sleep later because of distance learning to detail what they were seeing at home. There were some grumblings about teens staying up too late playing video games. But, overall, parents described their teens as more alert, more excited and engaged in schoolwork, and less combative with their siblings. Many noted that their adolescents were waking up on their own for the first time in years. And many said they were fearing the worst for their teens’ mental health upon school closures and the order to stay home, but are instead surprised by how well their teens seemed to be faring.

Parents shouldn’t be surprised, as it is entirely in line with research on the mental health benefits that accrue when schools delay their start times.

Parents began reporting happier teens and more peaceful family life since 1997, the year the very first large school district in America — Minneapolis public schools — delayed its high school start times from 7:15 a.m. to 8:40 a.m. In a follow-up study of those families, parents described their teens as “easier to live with.” They also reported spending less time arguing with their adolescents to get out of bed and get to school on time. Rather, parents were finding that they now had more time to converse with their teens in the mornings and were enjoying the new “connection time” the later school start afforded.

In that same study, the teens with later school start times reported fewer depressive symptoms, less school tardiness and truancy, and greater ability to concentrate in class and on homework.

In the subsequent decades, school districts across the country have delayed middle and high school start times and found similar benefits: decreases in depression, suicide ideation, substance abuse, and even car crashes.

And yet, nationally, still only 15% of public high schools follow science-based recommendations to start at 8:30 a.m. or later.

The COVID-19 pandemic will eventually wane, and our teenagers will likely return to school in the fall, overjoyed to see their friends and resume their normal routine. But, for most, “normal” means a school day that starts much too early for them to obtain adequate sleep. How long will their joy and optimism last when chronic sleep deprivation resumes? Can we, the adults responsible for the health and well-being of our children, learn from this experience of later school start times and enact appropriate policy changes?

If we do not, I fear one public health crisis will end, only for a more familiar one to return.

Katherine K. Dahlsgaard is clinical director of the Anxiety Behaviors Clinic at the department of child and adolescent psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.