How a medical mistake helped this doctor out of the cognitive bias trap

Even when we are in the wrong, it is never easy to accept it. So, instead, we search exhaustively to vindicate ourselves. But I think in doing so, it can distance us both from the truth and from ourselves.

I was urgently called to a patient’s bedside one morning. With the patient’s blood pressure falling and heart rhythm unstable, I decided it must be ischemia, a condition in which the heart isn’t getting enough blood flow, usually because of a blockage.

I quickly called my attending surgeon and explained how I wanted to treat the patient. Trusting my judgment, he asked me to start preparing for the procedure.

But then I ran into my senior resident, and told him what I was doing. He told me he also assessed the patient, and he said it wasn’t ischemia, pointing to a part of the patient’s chart I had missed. This patient needed a different intervention. We called the attending surgeon.

Fortunately, no harm came to the patient. But for a long time after, I remained disappointed in myself for having made the wrong call.

I spent a lot of time thinking about ways in which I could feel vindicated. I rationalized constantly and almost instinctively. What else was I supposed to think when suddenly confronted with this patient with these symptoms and this information? In my reconstructed memories, I wasn’t wrong – I was misled. The colleague who called me to the bedside had failed to mention a crucial detail, and it had not been charted properly.

Anyone else in my position would have come to the same conclusion, I told myself.

Nobody wants to be wrong, especially about something as important as a patient’s well-being. No matter who we are or where we come from, our worldview instinctively centers around ourselves as protagonists with good intentions and noble judgment. So we are constantly looking for alternate narratives that support our own opinions or conclusions, and help us feel good about our decisions.

While this tendency helps preserve our self-esteem, it also makes us vulnerable to what’s known as a cognitive bias. My experience in the hospital has taught me how important it is to recognize and examine this kind of thinking. Because while my rationalizations temporarily helped me feel competent, they never led me to the truth.

As a physician, I find this bias particularly fascinating because it is the opposite of the scientific method, which bases conclusions on evidence. Instead, cognitive bias tries to skew or recall information in a way that leads to a self-serving conclusion – sometimes even in the face of evidence to the contrary.

In these moments, we have to confront the discomfort of being wrong.

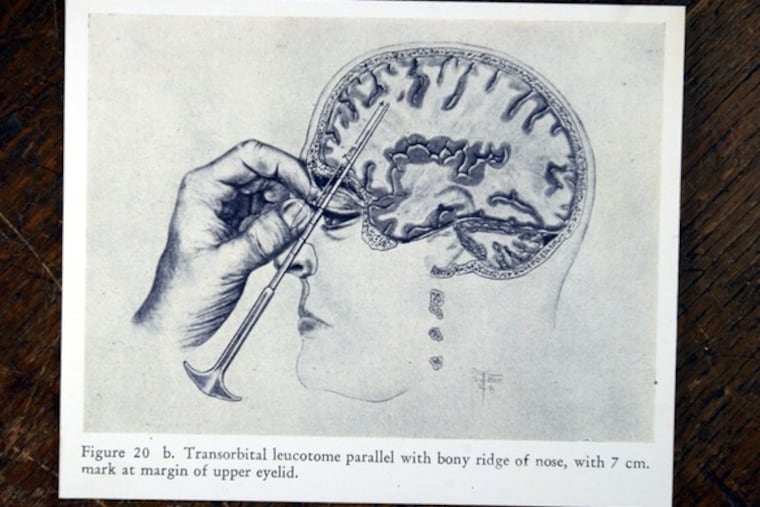

The history of medicine is full of mistakes. Numerous harmful procedures, such as lobotomies and blood-letting, have been performed under the illusion that they had health benefits. Back in the 19th century, doctors clung to the belief that washing hands before delivering a baby was unnecessary, long after the life-saving benefits of sanitation were well-established.

Where would we be today if we never sought out the truth instead of rationalizing the status quo?

Even when we are in the wrong, it is never easy to accept it. So, instead, we search exhaustively to vindicate ourselves. But I think in doing so, it can distance us both from the truth and from ourselves.

The whole time I was rationalizing, I thought I was coming up with ways to forgive myself. I thought I was generating a narrative that would help me overcome a deep sense of guilt and disappointment.

However, in the end, I was wrong again. The simplest — though not easiest — way to forgive myself was to accept that I am a human being who makes mistakes, but can use the experience to become a better physician. Not just one who clings to wrong beliefs because it feels good.

Ultimately, that is the only conclusion that we cannot change, and I hope I have done that ever since.

Jason Han is a resident in cardiothoracic surgery in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. The opinions expressed in this article do not represent those of the University of Pennsylvania Health System or the Perelman School of Medicine.