Getting mental health care can be hard enough. Then comes paying for it.

Despite two federal laws that were instituted to bring parity between mental and physical health care coverage gaping holes remain in behavioral health coverage. Insurance companies continue to interpret the rules for mental illnesses in a much stricter and more limited fashion.

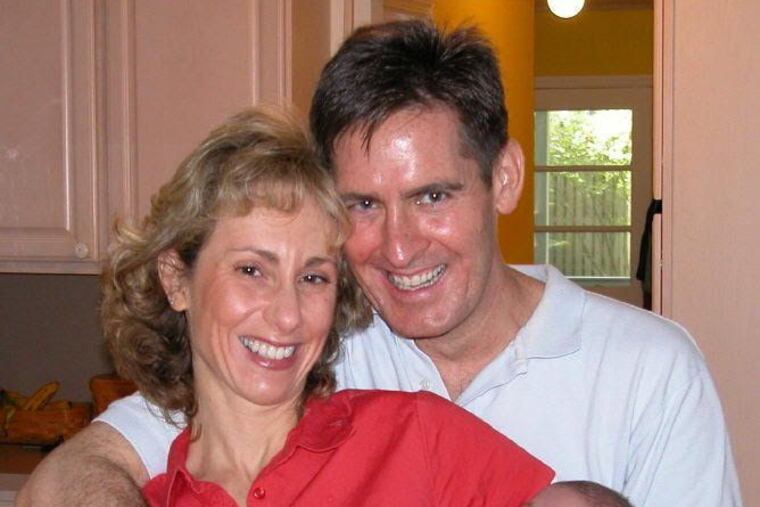

Joe and Enita Dugan’s son has long struggled with impulse control, depression, and anxiety. He started therapy at age 7 and medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at 9.

After a run-in with the legal system in middle school, the Dugans had him tutored at home. Eventually they transferred him to a new school where he still had trouble regulating his emotions and maintaining relationships with peers.

“The litany of psychiatrists we went through, and the medications we went through,” Enita recalled. “We didn’t find anything that was going to cure him or just get him through the day.”

Joe Dugan, who works as a financial adviser for a large wealth management company, said they were also increasingly worried their son (whose name they are withholding to protect his privacy) might harm himself or someone else. “A psychiatrist said kids like him become addicted, detained, or dead,” Joe said.

Eventually, the Dugans, of Linwood, N.J., placed their son, now 16, in residential treatment in Utah. He was there for a year-and-a-half, though the Dugans’ insurance company, United Behavioral Health, started denying their claims in September 2018. The family paid the $12,000-a-month price tag out-of-pocket, using up their savings and taking out a second mortgage.

The Dugans had to bring their son home in late December, not because he was ready, but because of the cost, Joe said.

He and Enita are panicked, frustrated, burned-out, and angry: “How many years have we paid in?” Enita asked about their health insurance policy. “They always want their premiums every year, and when we need [them] it’s deny, deny, deny. This kid needs help.”

Despite two recent federal laws meant to bring parity between mental and physical health-care coverage, gaping holes remain in how behavioral health costs are paid.

Insurance companies continue to interpret the rules for mental illnesses in a more limited fashion than they do for physical illnesses, according to the Milliman Report, a recent study of insurance claims in all 50 states. The study demonstrates that out-of-network use of behavioral health providers is higher than for medical providers, supporting the experience of patients and families who have trouble finding in-network mental health providers. The disparity between physical and mental health coverage has grown substantially in recent years, according to the Bowman Family Foundation, which commissioned the study.

At the same time, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown a steep decline in U.S. life expectancy for the last three years, primarily due to drug overdoses and suicides, otherwise known as “deaths of despair.”

“If there’s one statistic that should be a wake-up call for America, it is that over the last three or four years, the life expectancy rate is going negative, and that has not happened for over 100 years, not since the great flu epidemic of 1918,” said Henry Harbin, a Baltimore psychiatrist and mental health advocate. Former CEO of Magellan Health Services and adviser to the Bowman Family Foundation, Harbin said that “we have more money being spent on behavioral health than ever, and yet we have a worsening set of outcomes, morbidity and mortality.”

‘Red tape to get through’

The paperwork hassles and low reimbursements mean that many psychiatrists and psychologists won’t accept insurance, leaving patients to pay up-front and hope to recover partial reimbursement.

Brad Norford, a licensed psychologist who owns Bryn Mawr Psychological Associates on the Main Line, decided not to accept insurance when he opened his practice – now with 12 full-time psychologists – 20 years ago.

Working for a practice that took insurance, “I would see firsthand the struggles the facility would have, as well as me trying to get payment from the insurance companies in different cases – the paperwork, the red tape to get through,” Norford recalled.

Over half of patients with behavioral health issues never even see a specialist, relying on their primary-care provider who may not offer consistent screening or tracking of outcomes, Harbin said.

“We know from study after study that the quality and effectiveness of the care given in primary care to these folks with behavioral diagnoses is very poor,” Harbin said.

“So how would you ever fix behavioral health outcomes in America with you not addressing that?”

You can’t, according to former Congressman Patrick J. Kennedy, who helped write the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act requiring large group health plans to cover physical and mental health in the same fashion.

“What I was hoping was that the federal law was going to act as a good impetus for AHIP [America’s Health Insurance Plans] to come together and say, ‘Hey, fellas! This parity thing is going to become a bigger and bigger problem for you because we’re not going to be able to comply with it,' ” Kennedy said.

Kennedy, who lives in South Jersey, travels the country on behalf of the Kennedy Forum, a nonprofit that helps people challenge insurance denials for behavioral health claims.

“I have no doubt in my mind that we can cut in half the numbers of lives lost if we spend on deaths of despair the same amount we spend on HIV/AIDS,” he said.

That is in part what the National Alliance of Healthcare Purchaser Coalitions – a nonprofit dedicated to driving health-care value – has been trying to do, said Harbin. One of the alliance’s goals is early screening for behavioral health issues by primary-care physicians, OB-GYNs, and pediatricians – and then referring to the appropriate care. Another major goal includes “getting employers and insurers together with providers to make this a priority,” Harbin said.

An example of how such a system can work is a program at the University of Pennsylvania, where psychiatrist Cecilia Livesey and primary-care physician Matthew Press have been spearheading a collaborative care model.

Patients of eight Penn primary-care practices seeking mental health assistance are scheduled for a screening with a virtual resource center and then connected to the appropriate mental health provider, usually a licensed clinical social worker embedded in the primary-care practice. For some patients, the social worker, in conjunction with the primary-care provider and the consulting psychiatrist, offers all the care they need through brief behavioral interventions. For those with more complex issues, the resource center connects them to specialty psychiatric care.

Instead of the approximately 500 patients the staff of the eight Penn primary-care practices involved expected to participate in the first year, they received more than 6,000 referrals in 2018 and more than 14,000 by the end of 2019. More than 1,400 patients at risk for suicide were identified through the assessment process, as well as hundreds with symptoms of mania, psychosis, or post-traumatic stress disorder, according to Livesey.

“Our depression and anxiety scores have been around 50% remission, so that’s really exciting, and the [primary-care] providers totally love the program,” Livesey said.

‘The most vulnerable point of your life’

Meanwhile, the Dugans are grappling with their insurer’s insistence that their son can get by with a much lower level of care than his doctors think he needs.

The company vowed to consider their case. “We want our members to have access to the behavioral health support they need, when they need it, as part of our broader commitment to accessible, quality care,” Maria Gordon Shydlo, communications director of UnitedHealthcare, of which United Behavioral Health is a subsidiary, said in a statement. “… We will continue to work with the family and the member’s doctors to address coverage of his health care needs under his plan.”

In fact, the insurance company had not been in touch with the Dugans for months. But after a reporter called the company, the Dugans received several calls from UBH inviting them to file an appeal, even though the two appeals they previously filed were denied.

“While I want this conflict with the insurance company to go away, I also want people to see how poorly you can be treated when you’re in perhaps the most vulnerable point of your life,” Joe Dugan said. “I’ll be working an extra 10 years as a result of all of this.”