Philadelphia’s black teen boys lose so many friends to gun violence. Studying how they grieve might help.

To this Penn researcher, the rituals of grieving seem as much about brotherhood and deepened bonds with those still living as they are about remembering those who have died. She hopes her findings could lead to better support systems.

One out of every 12 shooting victims in Philadelphia was under age 18 in 2018, and the toll only grew worse in 2019.

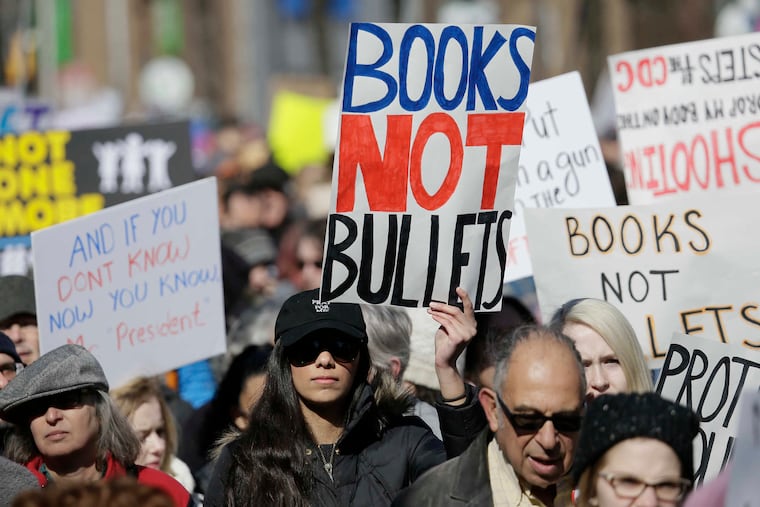

As gun violence in the city grows, children are increasingly the victims.

Although the families bear the greatest sorrow, others in the victims’ orbit suffer, as well. A University of Pennsylvania researcher has been studying the emotions and grief rituals of black teenage boys in Philadelphia who have lost a friend — frequently more than one friend — to gun violence.

Nora Gross, a doctoral candidate pursuing a dual degree in sociology and education, spoke to us recently about her work.

Your work has its origins in a tragic accident.

In 2008, I was a high school teacher at an all-black charter school in Chicago. In a devastating freak accident, we lost three beloved students. Everyone at school was distraught. However, just days before, Obama had been elected president, and among many black folks and Chicagoans in general, there was a profound sense of hope and revelry across the city. But I remember noticing how much more deeply — and for how much longer — my students seemed to be impacted by the loss of their friends than by Obama’s election.

In the weeks and months that followed, I saw the way so many of my students were deeply demoralized by their friends’ deaths. Some of them expressed legitimate anxieties about their own possibility of dying young — and therefore wondered about the point and purpose of all the work they were doing in school. But others took up this tragedy and their friends’ memories as motivation to work harder.

Even after I left teaching, those different responses stuck with me, and I wondered what more I and my colleagues could have done to support them.

What are you looking at now?

My research now focuses on the emotional experience of peer loss, specifically in response to neighborhood gun violence. My current project focuses on black adolescent boys, who are the group most affected by gun homicides — and consequently by the deaths of friends and classmates. I’m interested in how boys grieve after a friend is killed, how the policies and practices of their school help them manage their grief or recover, and how loss and grief impact the social life of a school over time.

My research has been based at a particular public school in Philadelphia, although I can’t share specific details.

I do ethnographic research, which means I collect data through spending long periods of time immersed in school life, getting to know both students and adults, observing how people interact with each other, and conducting interviews. The boys in my study also let me observe their activities on social media.

What’s one of the most interesting or compelling things you have learned?

In society, we have a host of stereotypes of black boys and black men as being unfeeling, unwilling to ask for help, emotionally stoic, or tough. We know where these stereotypes come from historically and how they benefit white supremacist structures of our society. And we also know, of course, that these stereotypes are not true. Black males’ emotional worlds are complex and multilayered. They feel deeply and profoundly.

If my only interactions with the boys in my study were in school — in classrooms and hallways and cafeteria tables — I might be inclined to think the stereotypes were not so far off. In general, especially at the beginning when I was a stranger to the boys, they often avoided emotional conversations, offered one-word answers if I asked how they were feeling, etc.

But what I’ve found is that online, in peer-driven social media worlds like Instagram, the boys I came to know are deeply emotional and expressive. They talk vividly about their pain, their grief, their love for their friends. They also talk about the strategies they use to cope, and they confess when they’re really not coping well or when they need help. Their digital lives offer another window into their emotional worlds which many adults in their lives, and certainly most of the adults in their schools, don’t have regular access to.

Tell us about the grief rituals of urban, black teenage boys.

When a young person is killed, there are often several organized rituals to bring loved ones together in the immediate aftermath. These might include gatherings to release balloons or light candles. In school buildings, people seem to instinctively want to create something tangible as a memorial — I’ve seen the deceased student’s locker decorated in photographs and messages, classroom walls covered in R.I.P. messages. Young people wear clothing and jewelry with their friend’s name or picture; they get memorial tattoos; they write R.I.P. or LL (Long Live) with their friend’s name or nickname on gym shoes, backpacks, hats, etc., so that they are always carrying them along.

But after these initial memorializations, grief rituals often continue among friends through online posts. They mark important dates — death anniversaries each month, birthdays. They post if they’ve had a dream about their friend. They share when they are doing something that reminds them of their friend or that might make their friend proud.

The boys in my research also lean on each other and support each other. If one person shares that he’s having a hard time, another friend might post an encouraging response or even give him a call. The rituals of grieving among black boys seem to me as much about brotherhood and deepened bonds with those still living as they are about remembering those who have died.

What concerns you most about what you have learned?

I know the whole city is concerned right now with what feels like an uptick in the murders of children and teenagers. Gun violence is on the rise in Philadelphia and young people unfairly bear the brunt of it.

I’m most concerned about all the young folks who are impacted secondarily by the deaths of friends.

Each time I read a headline about another young victim, I think about the dozens -- hundreds, even -- of friends and classmates that he or she is leaving behind. In addition to family, neighbors, etc., an entire school will be in mourning. In each of these schools, students, teachers, and administrators have to figure out how to get through the next day and the day after, and the next weeks, months, years with the absence of this person. And their absence was created in a way that surely has other kids thinking about who else they might lose, or whether they might be next. Whether their face might end up on a T-shirt or their name in a hashtag.

Students have told me that there simply isn’t enough time in the school day to process all the things they are going through. Some of the boys I’ve come to know — just 16, 17 years old — need more than two hands to count the number of friends who’ve been killed. The toll of these losses accumulates, but they have very few outlets to work through their grief. And the teachers they interact with every day, though they care deeply, are already pulled in too many directions and often feel wildly unprepared to serve as de facto counselors.

Schools are not equipped to handle the complexity of emotional responses from students and the long and unpredictable timeline of grief. Public schools have so much to do and they generally don’t have nearly enough resources to meet students’ academic needs, let alone their emotional ones. My hope is that the more we can understand about how young people grieve, the more we can help them.