Closing Hahnemann could deprive some struggling neighborhoods of a key safety net

Hahnemann University Hospital’s decision to turn away critically ill emergency patients comes at the start of the busiest season for health emergencies, when car crashes, gunshot wounds, and other trauma are on the rise.

Hahnemann University Hospital’s pending closure and immediate move to turn away critically ill emergency patients threatens a safety net that has served close to 150 emergency room patients a day — many of them poor minorities who rely on the hospital for even primary care.

Close to half of the people admitted to Hahnemann were on Medicaid and two-thirds are black or Latino, according to an Inquirer analysis of state inpatient billing data. The facility draws largely from North Philadelphia neighborhoods, many within walking distance, the data indicate.

Other Philadelphia hospitals, despite wait times that already are longer than average, say they can handle any extra traffic. But that hasn’t reassured Mayor Jim Kenney and city Health Commissioner Thomas Farley, who scolded the owners for their abrupt action.

“This is unacceptable on such short notice. This is the beginning of Fourth of July week, which in Philadelphia typically coincides with elevated levels of emergency transports,” Kenney and Farley wrote.

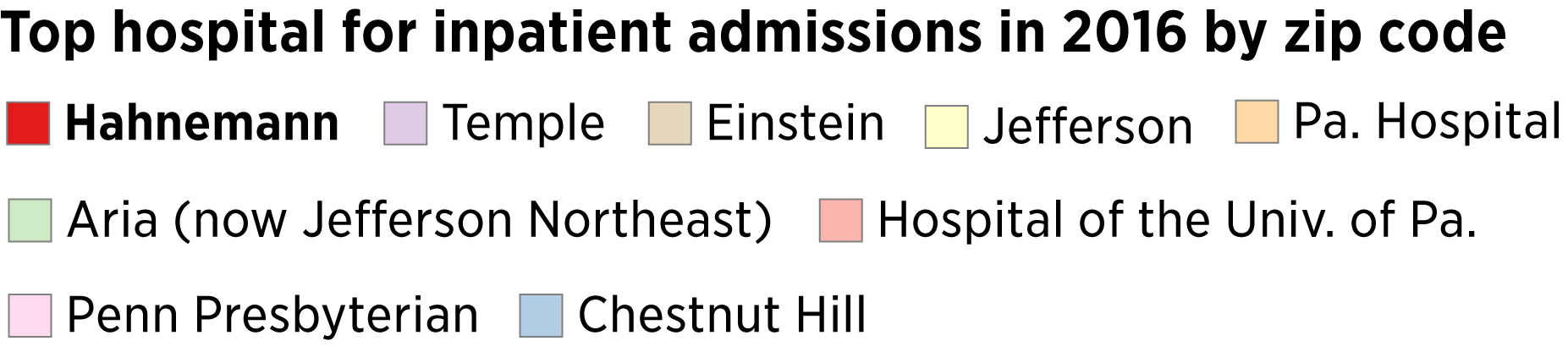

Where Philadelphia Hospitals Get Their Patients

Hahnemann University Hospital was the top pick for inpatient admissions in four of Philadelphia's 48 zip codes, and ranks sixth citywide among the nine hospitals with comprehensive emergency-room services.

Hahnemann’s owners have said the hospital will close in September, and they shut down a significant portion of operations on Saturday, closing the emergency room to trauma patients and those suffering from severe heart attacks. For now, it is still serving those with less serious complaints.

Sadrac Jeanlouis, 34, a painter who lives in a nearby shelter and has no health insurance, gave the Hahnemann staff a big thumbs-up Tuesday after being treated for a 102-degree fever. When he came in at 5 a.m., the waiting room was empty, he said.

“They were really nice," Jeanlouis said. "They took care of me.”

The backlog of patients is already high at some other emergency departments likely to take on Hahnemann’s patients, the most recent federal data suggest.

At Temple University Hospital, emergency patients waited a median of 49 minutes before seeing a medical provider, meaning half waited longer than that. At similar-size emergency rooms nationwide, the typical wait was 25 minutes during the most recent 12-month period available. At the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, the median wait time was even higher, 66 minutes, while the wait time at Hahnemann was 50 minutes.

Still, officials at Penn and Temple both said they had ample staff for the holiday weekend and beyond.

“Temple University Health System has been preparing for this situation since we first learned about the potential for closure of Hahnemann,” spokesperson Jeremy Walter said.

Likewise, officials at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, less than a mile from Hahnemann, said they “have staffing levels and contingency plans in place to absorb any impact.” Temple and Jefferson both said they saw no significant change in emergency room volume this past weekend, the first after Hahnemann started turning away critical patients, though they declined to provide figures.

Closing a hospital can spell trouble for emergency patients who must be taken to another institution farther away, especially for heart attacks, strokes, and other maladies for which every minute counts, said Renee Y. Hsia, a University of California, San Francisco, professor who studies the impact of hospital closures.

In a 2016 study in the journal Circulation, Hsia and colleagues found that heart attack patients were more likely to die within 90 days when the closure of a nearby emergency department meant that their resulting travel time increased by at least 10 minutes.

Even worse than delayed care would be none at all. If a patient has symptoms for which the underlying cause is not clear — vague abdominal pain or a severe headache, say — they might elect to stay home, said Hsia, a faculty member of the Institute of Health Policy Studies.

“If the hospital is farther away, you are less likely to go,” she said. “You might just ignore it.”

This could be a particular issue for Hahnemann patients, because low-income people tend to prefer emergency rooms over primary care physicians, believing the care they get is better, according to a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation study of Philadelphia hospitals.

But with more hospital beds per capita than many urban areas, Philadelphia is better equipped to handle the impact of a closure than many places, said Stuart H. Fine, an associate professor in Temple University’s College of Public Health.

“Philadelphia is fortunate to have enough hospital beds for the city’s needs, even if Hahnemann closes,” he said. “I’m not minimizing the impact of this closure on those patients who live right by Hahnemann, rely upon it for their care, and will have difficulty traveling to other locations."

Hahnemann had 17,000 inpatient stays and 53,000 emergency room visits in 2017, making it the eighth-busiest E.R. in the city, according to state Department of Health statistics.

Citywide, emergency department visits have climbed steadily in recent years. They typically were fewer than 950,000 per year a decade ago and now regularly topping 1,050,000, according to statistics collected by the Department of Health.

Fine said Philadelphia’s reliance on emergency rooms is a symptom of a greater problem: “Our emergency rooms are overflowing because so many people end up in E.R.s instead of receiving appropriate primary care and chronic disease management.”

The summer months account for one-third of U.S. emergency room visits each year, federal data show, and July in particular is prime time for outdoor excess that can raise the risk of injury.

Also a concern: with the holiday falling on Thursday, the Fourth of July will be the equivalent of a four-day weekend for many. That means a longer stretch of activities that can lead to emergency room visits: drinking, overeating, heatstroke — and, on this holiday in particular, burns and other trauma from fireworks.

Poor Philadelphians often suffer the most in the summer. In neighborhoods with block after block of paved strip malls and red-brick rowhouses topped with black-tar roofs, summer temperatures can be as much as 20-degrees higher than in leafier parts of the city, one recent study found. And without air-conditioning, heat-related health problems are rampant.