Biases in health-care algorithms | Philly Health Insider

And big construction plans at Jeff and CHOP

Good morning. Today, we’re bringing you news on how Philly hospitals are continuing to move away from outdated race-based decision-making tools.

Plus:

Is bigger better? Multimillion-dollar construction plans are underway at CHOP and Jefferson

The doctor will text you now: How doctors are communicating with patients in new ways

Changing codes: How Penn research led to new medical record reporting for sepsis patients

📮 Got tips, questions, or suggestions? For a chance to be featured in this newsletter, email us back. If someone forwarded you this newsletter, sign up here.

— Aubrey Whelan and Alison McCook, Inquirer health reporters, @aubreyjwhelan and @alisonmccook.

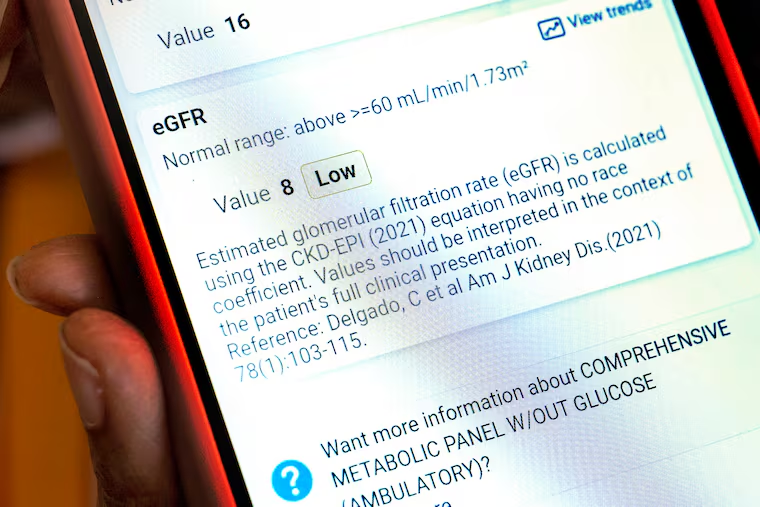

Health-care algorithms are often viewed as impartial. After all, they’re dispassionate computer programs combing through data to help determine the course of a patient’s care — not a human applying their own biases, unconscious or not, to the process. Right?

Wrong. Race is a bad variable for determining patient care, because it’s a social concept, not a scientific one. Sometimes, when algorithms include race in an effort to eliminate biases, it can improve care for everyone. But often when algorithms take race into account, especially when there’s no real reason to do so, it can lead to missed diagnoses and subpar care.

That’s why Philadelphia’s leading health systems announced this week that they will stop using race adjustments in four common screening tools for lung, kidney, and OB-GYN care. It’s all part of a wider effort by a coalition of local health systems and insurers to evaluate 15 health-care algorithms shown to discriminate and worsen racial disparities.

The latest changes could help diagnose anemia more accurately in pregnant Black patients, ensure that lung disease gets identified earlier in Black and Asian patients, and prevent unnecessary C-sections for Black and Hispanic patients. Read our colleague Sarah Gantz’s story for more on how Philly health systems are working to eliminate biased modes of thinking in medicine.

The latest news to pay attention to

Both Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Jefferson have big construction projects on the horizon. CHOP is borrowing $750 million to help fund a $2.59 billion patient tower and a $480 million research facility, Harold Brubaker reports. And Jefferson is selling $1.1 billion in bonds to restructure existing debt and pay for $530 million in capital improvements, including expanding the hospital system’s flagship ER in Center City.

St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children will receive $30 million from a coalition of Philly-area health systems to shore up its finances, after already receiving $50 million from this group in recent years. One reason for its money troubles: Most of the hospital’s patients are on Medicaid, which pays lower rates for care than private insurance.

After a hit-and-run outside Penn Presbyterian injured three nurses, hospital officials and nurses’ unions across the city say that more has to be done to protect health-care workers who routinely face violence on the job. They’re calling for the passage of a law that would make it a federal crime to assault a health-care worker.

Breast cancer surgeon and oncologist Monique Gary — better known as “Dr. Mo” to her patients — left city living in 2020 for a farm in rural Bucks County. Now, she hosts wellness retreats for cancer patients and survivors on the sprawling property, and invited our colleague Wendy Ruderman to a recent one. Come for the yoga and pond fishing; stay for the deep dive into Dr. Mo’s philosophy of holistic healing.

The big number: 106%.

That’s the percentage by which in vitro fertilization procedures increased between 2018 and 2022 at Shady Grove Fertility in Wayne, one of the region’s largest IVF providers. Growing demand for IVF has, in turn, meant enormous growth for fertility providers in the area.

Take Reproductive Medicine Associates of Philadelphia, which doubled the size of its Wayne clinic this year after hitting capacity at its former location in King of Prussia. The practice saw 2,800 patients last year and helped more than 1,000 patients become pregnant.

RMA, Shady Grove, and a third major fertility provider, Main Line Fertility & Reproductive Medicine, grew by a combined 130% between 2018 and 2022, more than twice as fast as the fertility medicine market as a whole. The three practices have another thing in common: They are all backed by private-equity firms.

Read Harold’s story for more on the demand for IVF.

Each week, we highlight the results from investigations into potential safety violations at area hospitals. Up this week: Jefferson Lansdale Hospital in Montgomery County, where state inspectors conducted no on-site investigations between February and July.

Is your practice into asynchronous communication? In less-fancy terms, that’s when a doctor and a patient communicate via text or email when convenient, instead of meeting in person or over telehealth.

Penn internist Jeffrey Millstein shares why he does it regularly — and talks about its drawbacks.

While sending messages through patient portals can be convenient, the sheer volume of these messages can overwhelm doctors. For more on how to make it easier for doctors to respond to patients’ needs outside the office, read his expert opinion for The Inquirer.

The National Academy of Medicine elected 100 new members this year — and eight are in our area, with expertise ranging from cardiovascular and community health to infectious disease. Read our story to see if there’s anyone you recognize. (A hint: If you read the bulletin board item, below, you will know at least one name on the list.)

The way that hospitals report sepsis in medical records is changing — thanks in part to a study from Penn researchers that showed that home-care workers and nursing home staff are often unaware that a patient they’re receiving survived this life-threatening infection.

That’s because the standard system for describing diseases in patient records and medical bills didn’t have a specific code for a patient who had survived sepsis — until now.

On Oct. 1, a new code for sepsis survivors was rolled out, meaning this crucial health information will now be at the forefront of a patient’s chart, instead of relegated to its “history” section. Read Sarah’s story for more on how the new code can help patients with sepsis.

📮 Do you think this change will help improve follow-up care for sepsis survivors? For a chance to be featured in this newsletter, email us back.

By submitting your written, visual, and/or audio contributions, you agree to The Inquirer’s Terms of Use, including the grant of rights in Section 10.