Her insurer’s price tool estimated less than $1,375 for a breast MRI. Then she got a bill for $3,200.

Insurers and health systems are increasingly investing in price estimator tools -- though they're not always helpful.

Michelle Smith knew the breast MRI her doctor ordered wouldn’t be covered in full by her insurance, so she turned to an online tool that her insurance company developed to help patients estimate prices.

UnitedHealthcare’s price estimator told the 51-year-old Delaware County resident that the cost for the procedure in her area ranged from $783 to $1,375.

So Smith was shocked when her share of the bill — from a facility that the tool suggested — came to $3,237.

“What good is a cost calculator if it’s not accurate? I’d be better off with no information than false information,” she said.

Health-care costs are difficult to pin down because prices vary widely and are part of confidential agreements between insurers and providers. But in response to growing demand from patients spending more out of pocket than ever before, insurers and even health systems are investing in price estimator tools that claim to offer at least a ballpark price. Still, the tools have been slow to catch on, in part because they’re clunky and, as Smith learned the hard way, not always useful.

“It doesn’t seem like too much to ask, ‘How much is this going to cost? What’s a provider that’s in-network?’ Those are reasonable questions and insurers need to improve their ability to answer those questions. They’re working on it, but they’re not there yet,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior policy adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Each insurance company negotiates its own set of rates with every provider in the network. The size of your health plan’s deductible (the amount you pay out of pocket before the plan pays) and how the plan splits cost between itself and its members after the deductible is met will also affect how much you owe.

These complicated plan designs, with their many ways members may be footing part of the bill, have made it even more difficult to pinpoint costs in advance, Hempstead said.

“There’s more opportunity for different types of bad surprises for consumers,” she said.

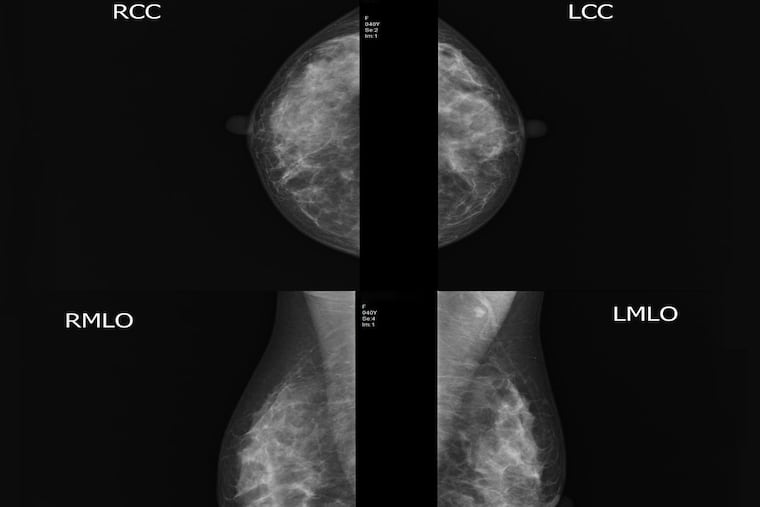

Smith, who has a family history of breast cancer, had a breast MRI last year at Main Line Health Imaging’s Bryn Mawr Hospital location, across the street from the hospital’s main building.

The scan cost Smith $1,500 last year, so UnitedHealthcare’s estimate of $783 to $1,300 seemed about right, she said.

Smith called the scheduling phone number listed for Main Line Health Imaging’s six locations and made an appointment at another facility near her Springfield home, this one at Riddle Hospital.

Little did Smith know that the imaging center at Riddle would cost her twice as much because the center is based within the hospital, as opposed to a separate building across the street.

Services provided in a hospital are often more expensive because the price includes fees for the administrative and operating costs associated with running a hospital, Megan Call, a spokesperson for Main Line, said in a statement.

When asked how a patient could have known which of the six imaging centers are billed at a hospital rate, Call said patients should call Main Line’s price estimation team for help.

“We do acknowledge that billing and insurance reimbursement issues can be difficult to navigate. As such, we are committed to price transparency and giving our patients the tools they need to make informed decision about their care,” she said in a statement.

Main Line billed UnitedHealthcare $7,692 for the scan and the insurer negotiated a rate of $3,463. Because Smith hadn’t met her deductible yet, UnitedHealthcare passed on almost all of the bill — $3,237.

After a call from an Inquirer reporter, Main Line reduced Smith’s share of the bill to $1,500.

Smith said she is pleased that the bill was reduced, but is concerned about getting caught in the same situation next year. (Her scan results were fine, but because of her family history, she will likely need a breast MRI annually.)

“I do not have a problem paying the bill. It’s not a financial thing for me. It’s a principle thing. I feel like I am an informed person and can’t accurately use the cost estimator — there must be plenty of people who can’t,” Smith said.

Smith said she believed that she’d taken every possible step to avoid a big bill and that the estimate UnitedHealthcare provided was misleading.

In a statement, UnitedHealthcare defended its cost tools.

“Our online and mobile quality and cost transparency resources provide estimates, which are based on actual contracted rates with health-care providers and facilities, as well as the member’s health benefits plan, offering people actionable information,” Maria Gordon Shydlo, a spokesperson for UnitedHealthcare, said in a statement.

It’s important to have the correct information about the exact procedure and where it will be performed, she said.

Shydlo also recommended that members ask their doctor how much the service will cost or call other providers in the area to compare prices.

That may not be helpful advice. Doctors typically have no idea how much their services cost because the prices depend on the insurer’s contracted rates. Other providers, such as an independent imaging center, may be able to tell you cash prices, but the rates they negotiate with insurers are proprietary.

But increasingly, health systems are tuning in to patients’ desire for information about cost.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requires hospitals to list the “chargemaster” price for every service, procedure and medication they have. But few people pay chargemaster prices, which are the starting point for rate negotiations with insurers. Plus, the prices are displayed in hard-to-interpret spreadsheets on hospital websites.

One of the loudest criticisms of price tools is that patients don’t use them, because they’re difficult to navigate, provide inaccurate information, or don’t result in significant enough savings.

“When they are [used] they’re not leading patients to spend lower amounts of money. That was really the goal of the price transparency tools,” said Anna Sinaiko, an assistant professor of health economics and policy at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Arming patients with more information about how costs vary depending on where they go can be a way for insurers to save money, too, if their price tools direct members to lower-cost providers.

“The idea of providing price information to patients in advance is generally thought to be moving the health-care system in the right direction,” Sinaiko said. “The more we demand this information from our insurers, the more pressure we put on them, that’s one way to get closer to that end.”