Philadelphia officials declare health emergency over hepatitis A outbreak

Typically, Philadelphia sees two to six cases of the liver infection per year. This year, there have been 154.

Philadelphia health officials have declared an emergency over an outbreak of hepatitis A in the city that has affected 154 people since January, and are calling for health providers to increase vaccinations to combat the liver disease.

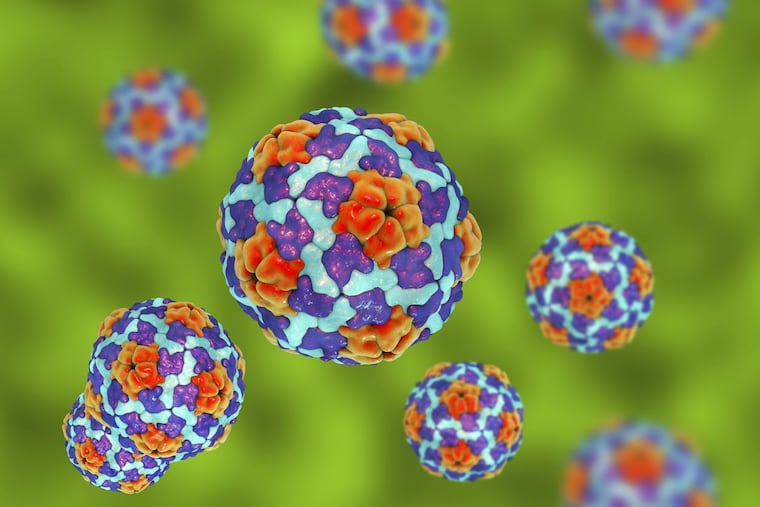

Hepatitis A is caused by a virus that spreads through oral contact with infected feces — usually after a person has consumed contaminated food or water. Typically, the city sees about two to six cases a year.

But cases of the disease began to increase this year, and accelerated this spring, with more than 130 people contracting hepatitis A since May alone.

Most of the city’s hepatitis A cases this year — 67% — have occurred among people who use drugs, who are typically at high risk for the disease, the Public Health Department wrote in its emergency declaration. Of those cases, 26% occurred among people experiencing homelessness, another high-risk population. Other populations at risk include men who have sex with men and people currently or recently jailed.

Many cases occurred in Kensington, the epicenter of the city’s opioid epidemic, which has a high concentration of homeless people in addiction.

Silvana Mazzella, the associate executive director of Prevention Point, a Kensington-based public health organization for people in addiction, said that in the spring, staffers began to notice that more clients were falling ill. Symptoms of hepatitis A can include vomiting, jaundice, and abdominal pain. While most cases resolve without treatment, the infection can be dangerous for seniors and those who are medically fragile or already have liver disease.

“The unfortunate thing is that when you’re unsheltered and living outside or in encampments, people do get sick, and it spreads,” Mazzella said. “Any time you have people living communally and don’t have access to public bathrooms — essentially places to defecate or to wash hands — you’re going to get an increase in infection.”

Stephen Gluckman, medical director at Penn Global Medicine and an expert in infectious disease, said mass immunization is key to combating the outbreak.

“The solution is to immunize — and there’s an extremely effective vaccine that’s close to 100% effective," he said. "The other solution is to try to improve the general hygiene in the area — by making sure there are enough clean places for people to defecate, and having access to things to clean your hands, something as simple as alcohol hand sanitizer.”

By June, Mazzella said, the city was vaccinating hundreds of people in Kensington alone; many clients at Prevention Point were concerned about getting sick and eager to get vaccinated, she said. The city is also installing public restrooms and hand-washing stations in the neighborhood.

Tom Farley, the city health commissioner, said it’s not clear why the outbreak began this year when hundreds of people have been living rough in Kensington for some time.

In May, Pennsylvania declared a hepatitis A outbreak after identifying 171 cases around the state, with 40 of them in Philadelphia. (Other states around the country have dealt with much larger outbreaks; more than 2,000 cases have been reported in both Ohio and West Virginia.)

“It may just be that the virus wasn’t introduced, and now, through bad luck, it was introduced,” Farley said. “We do know there are outbreaks that have occurred in similar populations in the rest of the country. In a way, we’ve almost been overdue for an outbreak.”

In light of that, the city stepped up vaccinations last year. But it wasn’t enough. In its emergency declaration, the city encouraged health-care providers to begin offering hepatitis A vaccines to groups at risk of contracting the disease. The city Public Health Department has vaccinated 1,775 people since last July, and more than 12,000 people have been vaccinated in Philadelphia as a whole in that time period.

“One of the key purposes of the declaration is to mobilize the medical community,” Farley said. “We’re optimistic we can contain it if we vaccinate people at risk.”

Gluckman said people can also protect themselves from hepatitis A by being more conscientious about washing their hands.

“This disease is fairly easy to prevent transmission — there are much more difficult diseases to prevent,” he said. “If you get vaccinated and wash your hands, you’re very unlikely to get hepatitis A.”