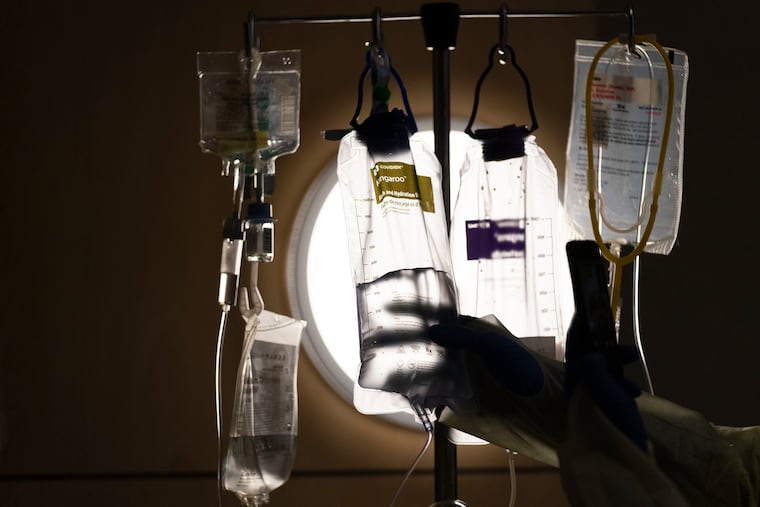

Some hospitals are giving patients Gatorade and oral medicine instead of IV fluids as they grapple with a shortage after Hurricane Helene

Some Main Line Health patients are receiving Gatorade to preserve supplies for the most critically ill. Other Philadelphia-area hospitals are using oral medications when possible.

Philadelphia-area hospitals are giving patients Gatorade and oral medications instead of IV fluids as they grapple with a national shortage of sterile IV fluids after a major manufacturer was shut down by Hurricane Helene in late September.

Storm damage has halted production at Baxter International’s North Carolina plant, which produces about 60% of the IV fluids used at hospitals, outpatient clinics, and ambulatory care centers in the United States. Baxter, as well as smaller manufacturers, are now limiting deliveries and have stopped accepting new orders.

The American Hospital Association, a leading industry association that represents 5,000 hospitals nationwide, has called for President Joe Biden to declare a national emergency and enact temporary rules to ease the shortage.

In the meantime, Main Line Health is giving some patients Gatorade and electrolyte drinks to preserve supplies for the most critically ill patients. St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children is looking for ways to reduce its IV use. Penn Medicine is giving patients oral medication, instead of through an IV drip. And administrators at Chestnut Hill Hospital, which is owned by Temple Health, are meeting three times a week to monitor supplies.

Penn Medicine and Jefferson Health said they do not rely exclusively on Baxter for IV solutions, but they will be closely monitoring their supplies, as another hurricane approaches Florida’s Gulf Coast with the potential to further disrupt the medical supply chain.

“Every day, almost every patient in the hospital has an IV in them,” said Jonathan Stallkamp, Main Line Health’s chief medical officer. “It’s something almost every patient is getting at some point, and to not have it makes things much more difficult.”

Hospitals troubleshoot IV fluid shortage

Main Line Health is currently able to get about 40% of the supply it normally receives from Baxter, Stallkamp said.

Dehydrated patients are being given liquids to drink, instead of IV fluids, when possible. Staff typically favor IV fluids to rehydrate patients because they work more quickly and because patients who are nauseated may have trouble keeping down liquids.

The hospital also uses IV bags to give patients medications, some of which can be administered through a syringe or smaller IV bag, instead, Stallkamp said.

The approach will help ensure the hospital has enough IV fluids for critically ill patients, such as those with sepsis, who need ongoing intravenous antibiotics.

Penn is developing “conservation approaches,” such as using oral medications when possible, to preserve supplies, Holly Auer, a spokesperson for Penn, said in an email.

Jefferson Health is “conducting frequent assessments of our inventory” and seeking other suppliers for IV fluids, Damien Woods, a spokesperson for the system, said in an email.

Less disruption at hospitals with alternative suppliers

Most Temple Health hospitals, including the main campus, do not use Baxter as their primary IV fluid provider. But in a staff memo, Chief Medical Officer Carl Sirio warned that their main supplier, B. Braun, had put a moratorium on orders, meaning a limit on how much health systems can purchase.

Administrators at Chestnut Hill Hospital, the only hospital in Temple’s system that contracts with Baxter, are closely monitoring supplies for shortages, he said.

Virtua Health receives IV fluids from Baxter, but the manufacturer is not the New Jersey hospital system’s primary provider.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Virtua leaders overhauled their supply chain, to ensure that it was receiving key medical supplies from multiple sources.

“We learned during COVID that the redundancy in supply chain is essential to make sure we have what we need,” said Eric Sztejman, a pulmonologist and vice president of clinical operations at Virtua.

The approach helped the system avoid crises when a Chinese plant that makes dye used during CT scans was temporarily closed, and when a supplier of blood culture bottles abruptly halted production, he said.

AHA calls for national emergency

Nationally, hospitals without such contingency plans are scrambling, according to the American Hospital Association.

The organization on Monday called on President Biden to declare a national emergency and temporarily loosen regulatory rules to ease the shortage.

Such official recognition would allow hospitals to prepare their own sterile IV solutions and share supplies, the organization’s president and CEO, Richard J. Pollack, wrote in a letter to Biden.

The government should also identify international manufacturers who could ship IV solutions, and work with U.S.-based manufacturers to increase production, he said.

“Patients across America are already feeling this impact, which will only deepen in the coming days and weeks unless much more is done to alleviate the situation and minimize the impact on patient care,” Pollack wrote.