Why a gentler, less costly approach to IVF remains unpopular

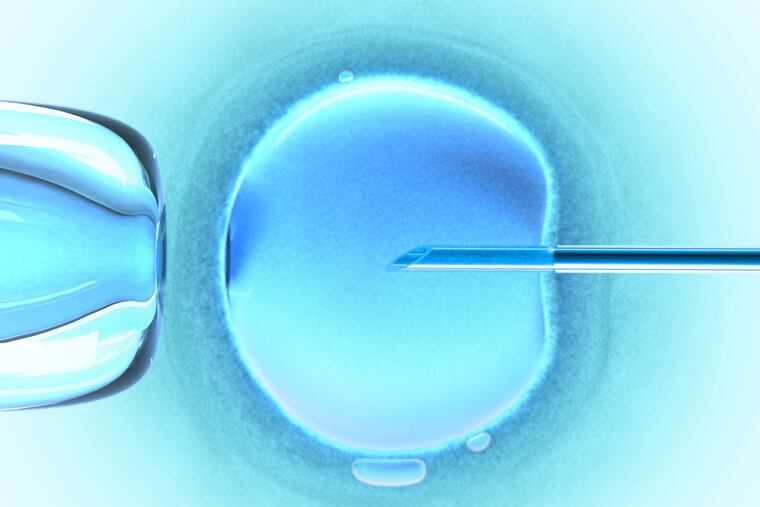

Risks and costs of in vitro fertilization can be reduced by using less drugs to stimulate the ovaries. But that also reduces the chance of a baby — which is the whole point of treatment.

There is a well-known way to make in vitro fertilization cheaper, easier, and safer for women.

Cut way back on fertility drugs that rev up the ovaries.

“Minimal stimulation IVF” aims to ripen just three to five eggs. Industry professional organizations say it can benefit several types of patients: So-called poor responders who ripen few eggs and have low pregnancy rates even with high doses of drugs; women at risk of dangerous ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, or OHSS; and those with ethical concerns about freezing leftover embryos.

Yet minimal stimulation has not caught on in this country. It accounted for only 2.4 percent of 208,000 IVF cycles in 2015, according to the latest national report from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART).

The reason for this unpopularity is basic, as the report also shows. Less stimulation generally means less chance of a baby.

“When we select patients for minimal stimulation, the live birthrate seems to be lower,” said Alan Penzias, a Harvard Medical School infertility specialist who chairs the practice committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM).

Experts who champion the less-is-more approach heartily disagree. But parsing the debate is tough because, like many aspects of high-tech baby-making, minimal stimulation is rife with hype, controversy, and variation. Last year, when the ASRM recommended that poor responders should give “strong consideration” to minimal stimulation, it lamented the lack of standard definitions and protocols.

“The terms ‘natural,’ ‘patient-friendly,’ ‘mild,’ ‘minimal,’ and ‘minimally stimulating’ in vitro fertilization have appeared increasingly in the literature, clinic advertising, and the media … causing confusion among clinicians, researchers, and patients,” the ASRM guidance said.

More success, more downsides

The world’s first IVF baby, Louise Brown, now 40, was created without fertility drugs. British doctors monitored her mother’s ovaries during a natural menstrual cycle, plucked out the egg that matured, fertilized it in a dish, then put the embryo in the uterus.

With the addition of daily injectable hormones that induce the ovaries to mature a dozen or more eggs at once, pregnancy and birthrates increased, but so did the discomfort, cost, and complications. Drugs, office visits, testing, and lab storage turn an IVF cycle into an average $20,000 investment. For women under 30 and those with a common disorder called polycystic ovary syndrome, conventional stimulation raises the risk of OHSS, in which the ovaries become swollen and painful; severe cases can be life-threatening.

Studies of minimal stimulation have found it eliminates OHSS.

The rebuttal is that tailoring treatment based on the patient’s age, risk factors, and monitoring has made OHSS rare. Studies suggest 1 to 5 percent of IVF cycles involve hyperstimulation, with severe cases far rarer.

At Abington Reproductive Medicine, infertility specialist Larry Barmat said he would cut the conventional dose of gonadotropin — a key drug in ovarian stimulation — by half or more for a patient with polycystic ovary syndrome.

“Those are the classic patients where you have to be very careful,” he said. “Mild stimulation has a role based on personalized medicine.“

Arthur J. Castelbaum, an infertility specialist at Reproductive Medicine Associates at Jefferson University, said another factor that has reduced hyperstimulation is judicious use of a shorter-acting drug to trigger the final stage of egg maturation.

Like other practitioners, Castelbaum said couples considering a minimalist approach need to discuss whether they want to create excess embryos to freeze for IVF attempts in future years. Frozen embryos can compensate for the fact that, in general, the quality and quantity of a woman’s eggs plummet after age 35.

“If patients would like minimal stimulation, that’s fine, but they have to realize they may have fewer opportunities to build their family in the future,” Castelbaum said.

‘Patient-friendly’ approach

New Hope Fertility Center in New York City bills itself as a pioneer of its trademarked “mini-IVF.” Most of the clinic’s patients opt for the regimen, which cuts the usual costs by about $3,000, said Zaher Merhi, the clinic’s director of IVF research.

“Despite using less medication, producing fewer eggs and transferring a single embryo, the minimal stimulation protocol has success rates that rival that of traditional IVF treatment,” says the clinic’s website.

New Hope founder John Zhang, a prominent fertility researcher, declared in a review article, “There is a misbelief that mini-IVF severely compromises pregnancy and live birthrates.”

Yet he led a clinical study that found it did reduce the chances — at least, for good responders. Among 564 such women, the birthrate was 63 percent with conventional stimulation, compared with 49 percent with mini-IVF.

In SART’s 2015 national report, New Hope’s data show that women of all ages had lower birthrates with minimal than with conventional stimulation.

Merhi said minimal stimulation is still better for many women because it is “more patient-friendly.”

“I recommend mini-IVF for women about age 37, because they tend to be lower responders and their eggs are more sensitive to overfeeding,” he said, adding he also advises it in cases of low ovarian egg reserves, polycystic ovary syndrome, clotting disorders, cancer patients who are freezing eggs, and women who just don’t like to take medications.

A 36-year-old New Hope Fertility Center patient said her situation was yet another reason for mini-IVF: she is extremely fertile but her husband’s sperm has motility problems. Two years ago, she produced three dozen eggs, despite mild stimulation. They used IVF because her husband’s sperm couldn’t reach the eggs, even when they tried uterine insemination.

Their second mini-IVF attempt resulted in their daughter, now 8 months old. “I was pleasantly surprised to find there is less medication and less needles than with conventional IVF,” said the woman, who requested anonymity to protect her husband’s privacy.

Japan’s experience

More than any country, Japan has embraced minimal stimulation, using protocols developed by Japanese infertility specialist Keiichi Kato in the 1990s at his Kato Ladies Clinic in Tokyo.

Norbert Gleicher, medical director at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York City, has analyzed the impact — and reached a scathing conclusion.

Between 2004 and 2015, “Japan lost two-thirds of its live birthrate. It went from 15 percent per IVF cycle to 5 percent,” said Gleicher, a faculty member at Rockefeller University. “That’s the lowest rate in the world.”

Japan’s decline coincided with some other changes in standard practice, including putting only one embryo in the uterus to prevent multiple births. But the result was that Japanese couples needed more IVF cycles to wind up with a baby, according to data Gleicher has published.

“Yes, mild stimulation is cheaper than conventional, but as Japan shows, if you need three cycles to get the same outcome, it’s more expensive,” he said.

Like other critics of minimal stimulation, Gleicher considers it mostly “a business model and a marketing model.”

“Who doesn’t want to use less medicine?” he said. “There are a significant number of people who believe using less medicine is cost-effective and is good medicine. And they are wrong.”