Federal prosecutors called him a ‘con man’; Penn Medicine hired him for a top job at Pennsylvania Hospital

Larry Butler’s tenure at Penn’s historic hospital in Philadelphia was short. A Google search reveals he had a history of theft from health care organizations.

Penn Medicine welcomed its new senior director of facilities at Pennsylvania Hospital in an email to staff that touted Larry Butler’s “long, successful career in health care” and highlighted his track record at a California hospital “where he served since 2015.”

But a quick Google search on “Larry Butler” and “hospital” would have revealed a string of recent news articles detailing a starkly different record:

Butler was not working for a California hospital in 2015. He was in federal prison after a judge sentenced him to five years for stealing tens of thousands of dollars from two health care organizations. Those organizations had hired him after he falsified his resume and Social Security number to conceal his criminal record. He even posed as his own professional reference, forwarding a call from a prospective employer to his phone, federal court records show.

His felony conviction resurfaced in news headlines last year when an Oregon hospital hired — and quickly fired — him as its chief operations officer after discovering that he had defrauded the two health nonprofits: Louisiana Health Cooperative in 2013 and Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center in Baton Rouge in 2014.

Similar to what played out at Oregon’s Bay Area Hospital, Butler’s tenure at Penn’s historic hospital in Philadelphia was short.

Butler, 58, started his new job at the Center City hospital on July 17, providing operational oversight, including building security and safety and capital project management, according to an all-staff email from Daniel Wilson, Pennsylvania Hospital’s acting chief executive officer.

Then, on Aug. 14, in a second email to colleagues, Wilson wrote that Butler had “resigned” with no further explanation, beyond saying that the search to fill the “key leadership position” would continue.

Penn declined to discuss how it vetted Butler, whether it ran a Google search on him or knew about his criminal history before offering him the job.

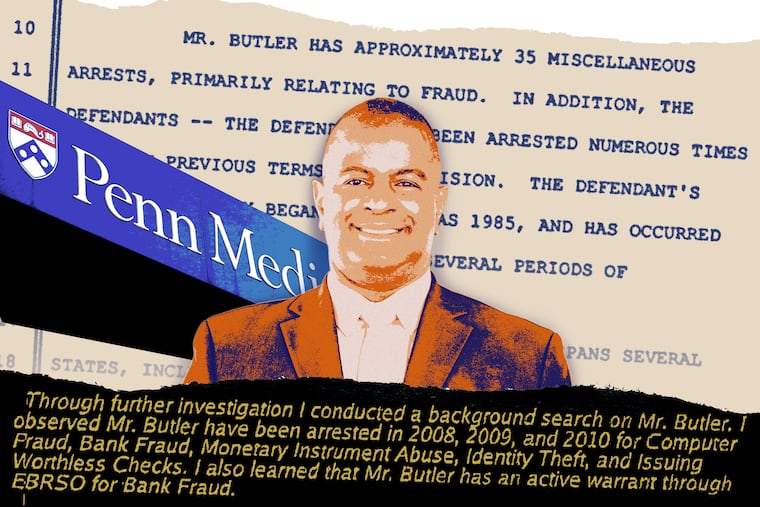

Federal court records, reviewed by The Inquirer, detail how he used phony credentials to conceal what a U.S. District judge described as a “long and complex criminal history.” He then got high-level jobs with access to company credit cards. Once hired, he stole a total of nearly $119,000.

According to Penn’s email announcement, Butler obtained a prestigious facilities management certification from the American Hospital Association, a national advocacy group. The Inquirer found no record of the credential.

Butler’s hiring by Penn Medicine raises questions about how one of Philadelphia’s largest health care organizations and employers screens job applicants.

Penn is charged with protecting patient security and privacy while adhering to federal and local laws, including Philadelphia’s “Ban the Box” ordinance, that restrict queries into a job applicant’s prior arrests and convictions. The city’s 2011 ordinance came amid a nationwide push to enact state and local laws aimed at giving people with criminal records second chances, even those with felony convictions.

But nothing would have prevented Penn from discovering Butler’s highly publicized criminal history and considering it before offering him the job.

In response to questions from The Inquirer, a Penn Medicine spokesperson said the organization has a “robust hiring process,” which includes background, reference checks and interviews. The spokesperson declined to provide further details, but noted that Penn complies with all laws related to hiring.

“Though candidates are expected to provide accurate information, these processes can allow for individuals who are not honest about their background to evade findings which may otherwise preclude their hiring,” the spokesperson said. “Importantly, during this individual’s very brief employment here, he did not have access to any patient information or financial systems.”

In an interview with The Inquirer earlier this month, Butler said his criminal record never came up during the hiring process, though he anticipated it might and was prepared to respond to Penn.

Butler said he “embellished” parts of his resume, “like a lot of people do,” which he said included “some dates” on his resume, such as falsely saying he worked at the California hospital since 2015. He was concerned that employers would not consider a convicted felon for well-paid management jobs.

“I’m just trying to work. That’s all,” said Butler, who noted that he was qualified for the Penn Medicine job, and he’s been a model employee since getting out of prison in February 2019. ”I want to move on.”

A net, ‘not a bucket’

Although Philadelphia’s “Ban the Box” law prohibits employers, both public and private, from asking job candidates whether they’ve been arrested or convicted of a crime on a job application or during an initial interview, that topic is allowed after the first interview. An employer may also conduct a background check after determining that “the candidate is otherwise qualified for the position” and making a conditional job offer.

A Penn spokesperson said the organization uses third-party vendors to help background and screen job candidates, but declined to identify the vendors.

Butler said he believes his 2015 felony conviction did not come up on the background check because many states restrict the “lookback” period to seven years.

Pennsylvania, however, is not one of them.

Pennsylvania law says potential employers can consider felony and misdemeanor convictions, so long as they are relevant to the position — no matter how old.

Matthew Rodgers, founder and president of iprospectcheck, a California-based background screening company with health-care clients nationwide, said a seven-year scope for criminal records research is the industry standard.

However, the depth of the research can vary. Some clients, for instance, opt to pay only for a search of local criminal records, not federal ones, Rodgers said.

In Butler’s case, a review of federal criminal records, reflecting his Feb. 8, 2019, release from prison — readily available on the Federal Bureau of Prisons inmate search webpage — should have come up, because the date falls within the seven-year lookback window.

Rodgers said it’s difficult to background people with common first and last names, and researchers, who cull through federal databases and court records, must be sure they have the right person before reporting back to a would-be employer.

Although Google can point a researcher in the right direction, he said, it’s not considered a reliable source.

“A background check is a net. It’s not a bucket,” Rodgers said.

And it’s doubly difficult to match people with criminal records if the job applicant provides false information to the client, he said.

» READ MORE: What do you think about our Eds and Meds content? Please share your thoughts in this brief survey.

‘I feel sick about this’

In 2013 and again in 2014, Butler managed to conceal his criminal history to obtain high-paying jobs in health care, according to federal court records that detail how he slipped through background checks.

In summer 2013, Butler applied for a top job at Louisiana Health Cooperative (LAHC), a now-defunct nonprofit near New Orleans that helped residents obtain low-cost health insurance.

By then, he had 10 convictions and about 35 arrests, mostly related to fraud and theft, spanning at least four states. He had been repeatedly incarcerated since 1985, court records show.

LAHC had used a background screening company to vet him, but Butler lied on his resume and provided a fraudulent Social Security number.

The health insurance cooperative hired him as its vice president of information technology, earning $168,000 a year.

Butler quickly racked up $31,000 in unauthorized charges on a company credit card, including multiple cash advances. He also bought “high-dollar” furniture and appliances. LAHC fired Butler in December 2013 after learning he had fraudulently used the company’s credit card.

In May 2014, he was hired by Mary Bird Perkins Cancer Center in Baton Rouge, La., as its director of facilities management, with an $80,000 yearly salary. Again, he had provided a doctored resume, with phony dates of employment, and a false Social Security number.

Over two months, he spent almost $20,500 in unauthorized charges, including dining out, travel and retail shopping, on company credit cards. The charges included nearly $4,000 to rent a house in Nashville. He also withdrew cash that he transferred by wire. In August 2014, Butler emailed his boss to say he got another job. The company then learned about the credit card charges and alerted authorities, according to police and court records.

Susan Dickerson, the cancer center’s vice president of human resources, explained at the time that she and another employee had verified Butler’s references and realized later that he used a bogus Social Security number on the new-hire forms.

“I feel sick about this,” Dickerson wrote in an email to her boss in 2014.

Butler eventually pleaded guilty to wire fraud and false representation of a Social Security number. At sentencing, a federal prosecutor noted that Butler had pretended to be one of his own professional references, rerouting a call and telling a prospective employer, “Oh, he was a great employee.”

The prosecutor also said Butler altered a California driver’s license and obtained new identification, with revolving addresses, to make criminal background checks more difficult. Butler later redirected monthly credit card statements to himself to keep his employers from seeing the charges.

At sentencing, Butler’s defense lawyer blamed an insufficient background check that failed to show he had criminal cases across the nation. Federal prosecutors described him as a “con man.”

Judge John deGravelles, of U.S. District Court in Louisiana, sentenced Butler to five years in prison, with three years of supervised release, and ordered him to pay nearly $119,000 in restitution.

“Mr. Butler, you are obviously a very smart guy,” deGravelles told Butler at sentencing. “You have been able to get jobs with a salary that most people would envy, and yet you have abused positions of trust and continued to come back time and again to where you are today.”

Richard M. Upton, then an assistant federal public defender who had represented Butler, recalled having lunch with a state judge who wondered how Butler got hired with fake credentials.

“I’m a judge in this parish and I need three IDs to cash a check,” Upton recounted the judge telling him.

“I said, `Well, Bob, you’re just not as believable as this guy,’” Upton recounted. “He was a very smooth guy.”

A brief stint in Oregon

About a year and a half after Butler left prison in 2019, he got a job at a California hospital, owned by CommonSpirit Health, a Chicago-based nonprofit system with 140 hospitals in 21 states.

His job title was senior director of ancillary services, according to a CommonSpirit Health spokesperson, who confirmed that Butler worked at Mercy San Juan Medical Center near Sacramento from July 2020 until February 2022.

The spokesperson declined to answer questions about his employment. At the time CommonSpirit hired Butler, California law prohibited employers from asking candidates about their conviction history before making a job offer.

Butler said he voluntarily left Mercy San Juan Medical Center on good terms.

“No one would tell you that I wasn’t excellent,” he said. “My job performance was exquisite.”

Butler provided The Inquirer with two documents from his time at CommonSpirit: a commendation recognizing his leadership during the coronavirus pandemic and another announcing his promotion to senior director in spring 2021.

The CommonSpirit spokesperson declined to verify the documents.

Andrew Lacy, an employment lawyer with offices in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, said organizations generally don’t comment about former employees to avoid liability, or if doing so doesn’t serve its interest.

In May 2022, Bay Area Hospital in Oregon hired Butler as its new chief operations officer. The hospital quickly fired him after his criminal record came to light.

“Bay Area Hospital uses a comprehensive background check process to vet all of its hires,” the hospital said in a statement at the time. “Even the best system can be manipulated by an unscrupulous individual.”

Butler told an Inquirer reporter that he never provided “false information” to Bay Area Hospital, as a hospital executive reportedly said in an interview earlier this year with MedPage Today, an online publication covering the health care field.

“Listen, hospital organizations — they have to protect themselves,” Butler said. “They didn’t know if I was up to something nefarious. I wasn’t, but I understand why they would react that way.”

Talking about his criminal cases in Louisiana, he said: “What I did wasn’t ... violent or hurting anybody or anything. It wasn’t anything like that.”

Cutting ties with Penn

Penn’s announcement of Butler’s hiring revealed still more inconsistencies in what his recent employers knew about his background, an Inquirer review found.

Penn told its staff that Butler holds a bachelor’s degree and master’s in business administration from Saint Paul’s College in Virginia. A similar hire announcement, put out by Oregon’s Bay Area Hospital in a news release and detailed in a local news report there last year, made no mention of Saint Paul’s College. The report referenced two different higher-education institutions.

The Inquirer was unable to verify Butler’s educational credentials, as shared by Penn, because Saint Paul’s closed in 2013.

During a January 2015 federal court hearing, Butler told a judge he had attended three colleges, but never finished. St. Paul’s was not among the colleges Butler named.

Penn’s announcement also noted that Butler is a CHFM, or certified health care facility manager.

Ben Teicher, a spokesperson for the American Hospital Association (AHA), which offers the prestigious certification program, told The Inquirer, “No one by the name Larry Butler currently holds a CHFM certification.” Penn’s job posting for the now-vacant position says its ideal candidate should have CHFM certification, or equivalent.

The Inquirer was also unable to confirm what Butler shared with a reporter about how Penn vetted his record. Butler said Penn used a company called GoodHire to research and run a background check on him.

Rachel Bodony, a spokesperson for GoodHire, told a reporter that the company “has no record of a Larry Butler in its system,” and that Penn Medicine has never been one of its clients.

Penn declined a reporter’s request to provide the vendor’s name.

Butler said he had relocated to Philadelphia “on his own dime.” While he earned “more than” $100,000 in annual salary at his previous hospital job in California, Butler said he took the Pennsylvania Hospital job for about $12,000 less. He declined to specify salary amounts.

Butler quickly settled into his second-floor office near the Radiology Department at the hospital at Eighth and Spruce Streets, which has 493 licensed beds. His “immediate priority,” Butler said, was to improve the hospital’s cleanliness.

Butler was three weeks into the job when a colleague alerted him that information about him had surfaced, he said.

“They wanted to check it out, investigate it,” Butler said. “Once they said that, I went home, licked my wounds, and just decided to resign. There was no kerfuffle.”

He said he didn’t want to put Penn Medicine in an uncomfortable spot. Butler now plans to seek employment outside of health care, he said.

“Actions have consequences — sometimes longer than we would like,” Butler said.