Medical dye used to diagnose tumors and blood clots in short supply at some Philly-area hospitals

Another shortage of a critical medical supply is highlighting the fragility of America's supply chains.

China’s COVID-19 lockdowns have created shortages in the United States of an injectable dye critical for some medical scans, forcing some hospitals to conserve their supplies and put off procedures.

“We may have to triage more elective procedures,” said Chun “Dan” Choi, vice president of clinical operations for the cardiovascular service line at the New Jersey-based Virtua Health. “We need to be a little more creative and sensitive and diligent in how we continue conducting business as usual.”

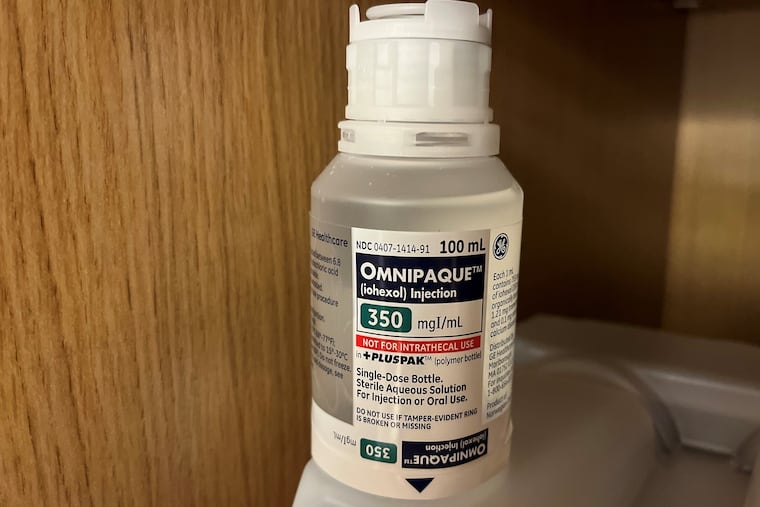

The scarcity of iodinated contrast media, used to make tumors, vascular blockages, and other issues visible in CT scans, joins the nationwide shortage of baby formula as the latest example of the pandemic’s health fallout. Both are caused by disruptions at central production facilities made especially painful because so few companies produce these items. In the case of the contrast dye, the disruption was a COVID lockdown in Shanghai that temporarily closed a GE Healthcare plant that’s the primary supplier of the dye to the United States, the American Hospital Association said.

“We need to find effective strategies for what I would call fattening the supply chain,” said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality and patient safety quality at the association. “One plant going down should not cause a crisis in the American health-care delivery system.”

GE is one of the biggest suppliers among the small number of companies that produce the dye used in about 50 million medical scans a year nationally, said Matthew Davenport, a radiologist and vice chair of the American College of Radiology’s commission on quality and safety.

GE alerted hospitals that it would be rationing orders on April 19, according to the AHA. The company called the speed and scale of the lockdown “unprecedented,” closing the plant for several weeks. The plant is open again, though not producing at its full capacity.

“We are working to return to full capacity as soon as local authorities allow,” a statement from the company said.

GE has also begun shipping from both Cork, Ireland, and Shanghai by air rather than sea, the company reported, to speed delivery of the dye.

Complicating matters, Davenport said, are contracts that give hospitals a better price if they commit to only one company as their provider of contrast dye.

The shortage prompted the Pennsylvania Health Department to issue a health advisory May 16 stating that supply problems are expected to last through June, and emphasized that no state or federal stockpile of the contrast dye exists. Deliveries are shipping at 15% to 25% their normal volumes, the advisory stated, and hospitals may not be able to switch to another supplier, as some are not accepting new customers.

GE said that the company has shifted production to its Irish plant, and that the situation had improved since the health department released its advisory. The company reached this weekend 60% of its normal production at the Shanghai plant and expected supplies to improve in the coming weeks.

» READ MORE: WHY WE STAY: As hospitals hemorrhage staff, healthcare professionals share stories of caring and perseverance.

Several Philadelphia-area hospitals have said they either do not rely on GE for their dye supply or have enough to manage urgent and emergency conditions.

“It has made life more difficult, but I think that there are often alternatives to this,” said Saurabh Jha, a radiologist and associate professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Hospitals use enormous amounts of the contrast dye, said Choi, who noted that a single facility can receive a truckload or more monthly. In some cases, an MRI, CAT, or VQ lung scan — which does not require contrast dyes — can be used instead of a CT scan, physicians said. Other procedures that require CT technology, such as scans to determine the effect of cancer treatments on tumors, can be delayed without hurting a patient’s care.

Temple University Hospital reported that it may turn to other types of scans to manage the shortage, and Main Line Health said it would do the same and would delay some nonemergency studies. In a few cases, Virtua was delaying tests that weren’t for emergency or urgent care.

“Our planning is such that at no point should any emergent or urgent case be impacted,” Choi said.

Penn hospitals buy dye from a different supplier, Jha said, and have not been affected.

Some procedures, though, can’t be done without the iodine-based contrast dye. The material absorbs more X-rays than the surrounding tissue, Davenport explained, causing it to show up brightly in a CT scan or X-ray based study. Mapping the interior of the vascular system requires the dye, said Choi, which allows doctors to identify clots or blockages and helps them insert stents without an invasive procedure.

“Without the anatomy of the coronary arteries, we’re not going to be able to know whether we’re in the right vessel, whether we’re in the right region, whether we’re successful,” Choi said.

Spotting signs of a stroke in a brain, identifying heart malfunctions, even identifying internal bleeding in victims of traumatic injury all can be done most effectively with the dye, health experts said.

To make supplies last longer, Jha said, doctors can use as little as half the normal dosage and still get effective views of a body’s insides while being less wasteful.

» READ MORE: Medical PPE is still so scarce after months of COVID-19, volunteers keep hunting for lifesaving supplies

While there are ways hospitals can adapt to the shortage, Davenport said, those adjustments may mean some scans will be slightly less precise or less detailed.

“What’s being missed or underrepresented is not totally clear,” he said. “I’m hopeful that the harm is small but we just don’t have a good grasp on what that’s going to look like.

If the shortage ends by July, as anticipated, most hospitals should be able to manage, Foster said. If the current production problems linger, or if another lockdown or a natural disaster creates a new disruption, patients could be seriously affected. Scans considered nonurgent at one point can be put off for only so long before they become necessary, she said, and if the supply issues aren’t resolved, hospitals “could reach a crisis with emergent cases colliding with these delayed procedures.”

The dye shortage is just the most recent to afflict health care over the last two years, exposing a surprisingly vulnerable supply chain for critical items. Shortages of masks and personal protective gear were well-publicized at the beginning of the pandemic, but since then there have been shortages of some medicines, Foster said, and even oxygen supplies were limited in the southern United States after an ice storm cut power to a production facility in Texas.

They are all rooted in an overly centralized supply chain, she said, that relies on few production sites to manufacture essential products. As with the contrast dye, many of these products are also manufactured overseas, she said, making them potentially vulnerable.

Lean supply chains, she said, keep products affordable, but at the expense of flexibility.

“The question to really ask GE and a lot of these organizations is why are they putting all their eggs in one basket?” Jha said. “These are the sort of issues that don’t get tackled because nobody really cares until you have a crisis, until all hell breaks loose.”