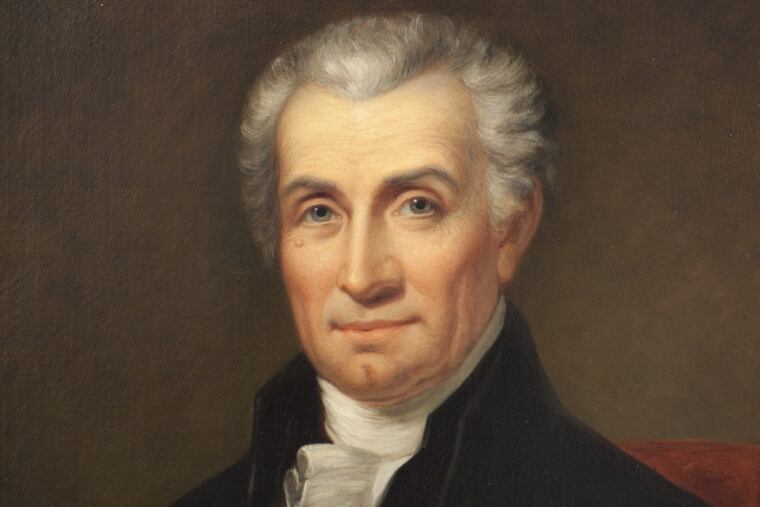

Medical mystery: Was it really malaria that plagued our fifth president?

Despite his many ailments, James Monroe achieved an astonishing amount for the new United States.

In 1785, while traveling through swamps along the Mississippi River, James Monroe, then a U.S. congressman from Virginia, became quite ill with what doctors diagnosed as malaria.

Later in life, Monroe had several episodes of fever, thought to be probable flare-ups of malaria. He spent over 50 years in the service of his country including multiple ambassadorships in Europe before he served as our nation’s fifth president from 1817 to 1825.

Thomas Jefferson sent Monroe to France in 1803 to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase, which nearly doubled the size of the new country. Monroe later became governor of Virginia, and was both secretary of state and secretary of war to President James Madison during the War of 1812. Some historians have held that the stress of his many duties might have contributed to his poor health.

In March 1815 and again in 1818, Monroe was bedridden with fevers of unknown origin. Even so, he won the presidency, and after his 1817 inauguration, he went on a national tour at a time hailed as the “Era of Good Feelings.” The best-known achievement of his presidency is the Monroe Doctrine, stating U.S. opposition to European colonialism in the Americas.

Subsequently, in the late 1820s, Monroe’s fevers and weakness episodes became more severe and were aggravated by a cough that continued to worsen, joined by night sweats. In April 1831 Monroe wrote: "My state of health continues, consisting of a cough which annoys me night and day accompanied by considerable expectoration” not only of mucus but also at times blood. As the disease progressed, his breathing became even more difficult.

No specific diagnosis was made, although his doctor recommended rest at a hospital. Historian James Bumgarner wrote: “It is known that the illness lasted for several months and involved his lungs progressively. He had a harassing, exhausting cough, and suffered from more fever and severe night sweats.”

Was malaria, as physicians suspected, the root cause of this president’s health woes?

Solution

Today, medical historians believe Monroe’s symptoms point to pulmonary tuberculosis, a disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB). These bacteria usually attack the lungs, but they can also damage other parts of the body. TB spreads through the air when people with the condition in their lungs cough, sneeze, or even talk to another person.

Symptoms of TB in the lungs may include a mild to severe cough that lasts a few weeks or longer, complicated by loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, fatigue, persistent fever, and night sweats. Coughing may bring up phlegm, pus from a lung infection, or even blood.

In Monroe’s day, diagnostic tools such as X-rays and sputum lab cultures weren’t available nor was the special sputum chemical stain for AFB (acid-fast bacilli), and there was no tuberculin (PPD) diagnostic immune skin test.

Latent or inactive TB infection without cough can occur when the bacteria remain in the body, causing no symptoms, but can still be contagious to others. An inactive infection also can turn into active TB, which appears to have happened in Monroe’s case as he grew older and burdened with the stress of high office.

Just as there were no diagnostic tools in his day, neither were there effective treatments. The game-changing drug streptomycin was not introduced until 1943, followed by isoniazid (INH) in 1952. Yet the infection remains rampant today, affecting some 1.8 billion people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Most cases are latent, says WHO, which estimates that last year, 10 million became ill with TB and the disease killed 1.6 million.

James Monroe, the fifth U.S. president and the last of the Virginia Dynasty (Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe), died on July 4, 1831, of heart failure and underlying pulmonary tuberculosis, becoming the third president to die on Independence Day.

Allan B. Schwartz, M.D., is a professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology & Hypertension at Drexel University College of Medicine.