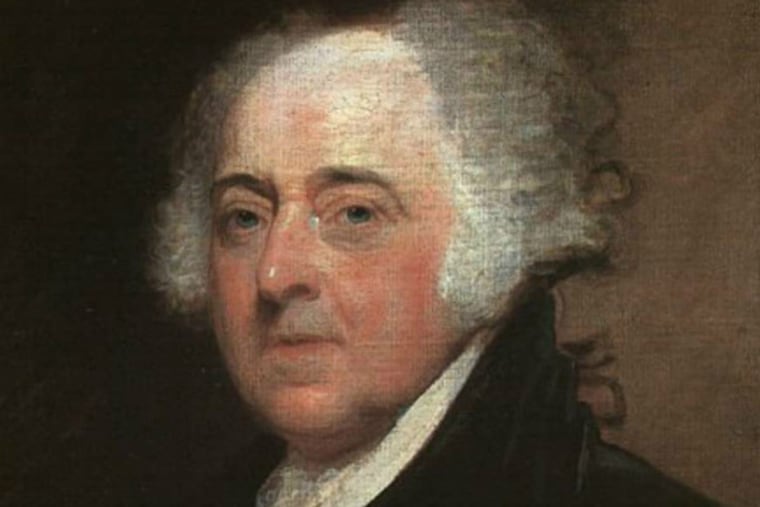

Medical Mystery: What made John Adams lose his temper?

The second president of the United States had to be kept in line by none other than Benjamin Franklin.

John Adams, the second U.S. president, was born with a proverbial chip on his shoulder. Contemporaries noted his frequent mood swings and behavior shifts. As a student, he suffered depressive episodes attributed to overwork. He abandoned early plans to study medicine, and instead went into law, disappointing his father, a Congregationalist deacon who wanted his son and namesake to enter the clergy.

People-pleasing seemed not to be one of his priorities. As a young, ambitious lawyer, he took on the task of representing British Redcoats accused of murdering five Bostonians. His neighbors were furious with him, but Adams insisted everyone deserved a fair trial. He won his clients’ acquittal.

In Philadelphia as a member of the Continental Congress, Adams argued passionately for independence from Britain. He was chastised by Benjamin Franklin for his bluntness, insulting other members for what he saw as their loyalty to the British crown. His temper alienated even those whose politics he admired.

He took his attitude with him to France in November 1779, when he was sent to negotiate an alliance at the court of Louis XVI. He behaved so undiplomatically, Franklin had him removed from the mission. From there, he became commissioner to the Netherlands to plead for financial aid to help his new nation. With his efforts meeting firm resistance, he became so unwell and withdrawn, he was said to be in a “coma” for five days.

He recovered after George Washington’s troops defeated the British at the battle of Yorktown in September 1781, and went on to greater diplomatic success in France and England. He was sent to negotiate the Treaty of Paris with the British, ending the Revolutionary War and later was appointed the first American ambassador to Great Britain.

On return to the United States, Adams was bitterly disappointed to come in second behind George Washington for President, although Adams served two terms as vice president. He won the top job in 1797 and moved into the presidential mansion, which back then was in the 400 block of Market Street, in Philadelphia.

Since age 25, Adams had suffered from a hand tremor which he called "quiveration." He passed this familial "essential tremor", a genetic disorder, along to his son, John Quincy Adams, who grew up to become the nation’s sixth president. Adam's tremor worsened under the stress of his new government responsibilities. For both father and son, this condition grew worse with age. As the newly inaugurated vice president, John Adams had trouble holding his speech steady so he could deliver it to the U.S. Senate.

What was the cause of John Adams’ varying temperament and other problems?

Solution

Modern historians have labeled founding father John Adams as manic-depressive, a condition more recently called bipolar disorder. This is a mental health condition characterized by extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Mental stress was clearly associated with the waxing and waning of Adams' bipolar episodes. Bipolar disorder most likely stems from a combination of genetic, environmental, and situational factors. John Adams' son, John Quincy Adams, also exhibited signs of depression. He did not, however, exhibit his father’s manic tendencies.

Between the highs and lows, periods of normal mood and energy are the rule. Mood changes can range from very mild to extreme, occurring gradually or suddenly within days to weeks.

Mania can involve sleeplessness, sometimes for days, along with hallucinations, grandiose delusions, or paranoid rage. Depressive episodes can be more devastating and harder to treat than in people who have depression, but do not suffer through manias. John Adams’ five days of supposed coma in the Netherlands may have been extreme depression and withdrawal.

There are two types of bipolar disorder: Bipolar I disorder involves severe episodes of mania and often depression. Manic episodes are at least seven days long, consisting of euphoria, increased libido, hallucinations, increased energy and less need for sleep. Bipolar II disorder, often called hypomania, is a less severe back and forth form that may involve: insomnia, hypersomnia, unexplained crying, fatigue, recurring thoughts of death or suicide.

Patients with bipolar disorder may also have disturbances in thinking, distortions of perception and social impairment. Some have few and only mild episodes; others have incapacitating symptoms that may impair their quality of life.

John Adams is considered to have been a bipolar II type, who without psychotherapy and modern medicines, overcame his symptoms to become the nation’s second president.

Allan B. Schwartz is a professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology & Hypertension at Drexel University College of Medicine.