What to know about mifepristone in Pa. following Supreme Court ruling that preserves access for now

What to know about the abortion pill mifepristol following the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in an ongoing case.

Philadelphia-area providers were preparing for the next front in the ongoing legal battles over abortion long as the U.S. Supreme Court on Friday weighed in on the abortion pill mifepristone, the first of a two-drug regimen used in more than half of abortions in Pennsylvania and nationally.

The high court ruled that mifepristone should remain available while dueling lawsuits play out.

Medication such as mifepristone was used in 18,370 abortions in Pennsylvania in 2021, about 55% of all abortions in the commonwealth that year.

Local abortion-rights advocates anticipated efforts by opponents to reduce access to the drug — which has been on the market for more than 20 years — after last summer’s U.S. Supreme Court decision to overturn its landmark 1973 abortion rights decision, Roe v. Wade. Since then, at least a half dozen states have banned abortion, which is no longer considered a national constitutional right.

“Just as we knew Roe was going to be overturned and prepared for it, we knew antiabortion activists and politicians weren’t happy with just Roe being overturned,” said Dayle Steinberg, CEO of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania, which operates clinics in Philadelphia and the surrounding counties.

Following the Supreme Court stay Friday evening, Steinberg said in a statement that she was “relieved.”

“Our health centers will operate as we always have — with doors open to the patients who need us,” she said.

The Biden administration called on the Supreme Court to protect access after a federal judge in Texas ruled that the Food and Drug Administration should never have approved the pill and sought to ban access to it nationwide. A circuit court subsequently ruled that the drug should remain available while the case advances, but with significant restrictions, including a ban on it being mailed to patients who are unable to pick it up in-person from a doctor.

In a separate case, a federal judge in Washington state ruled that federal authorities should not make any changes to restrict access to the medication in 17 Democratic-led states and the District of Columbia that are suing to expand access to the drug. Pennsylvania and Delaware are among the states involved in the lawsuit.

Adding to the confusion, the manufacturer of a generic version of mifepristone has sued to prevent the FDA from restricting access to the drug.

Here’s what to know about mifepristone:

What is mifepristone?

Mifepristone is a prescription medication used to end a pregnancy. It is typically used in combination with another medication, misoprostol. The FDA approved mifepristone in 2000 to terminate a pregnancy up to seven weeks gestation and in 2016 expanded use to 10 weeks.

Mifepristone is highly regulated and only available from a doctor who is specially licensed to dispense it, meaning it can’t be prescribed for pickup at a local pharmacy.

What happens if mifepristone is taken off the market?

There are other options for medication abortion. Misoprostol, the drug that is typically used in combination with mifepristone can be used alone, at a higher dose.

Misoprostol is safe and effective for abortion, but has more side effects — such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea — when used alone.

Some people may instead opt for an abortion procedure.

What are Philadelphia-area providers doing?

Planned Parenthood Keystone, which operates clinics in central and Southeastern Pennsylvania, have been training staff how to counsel patients about misoprostol-only abortion and providing training updates for doctors on how to provide medication abortion without mifepristone, said Melissa Reed, CEO of Planned Parenthood Keystone.

“Because of the political climate and the ongoing attacks on reproductive health care, we are having to be very nimble,” she said. “We have prepared.”

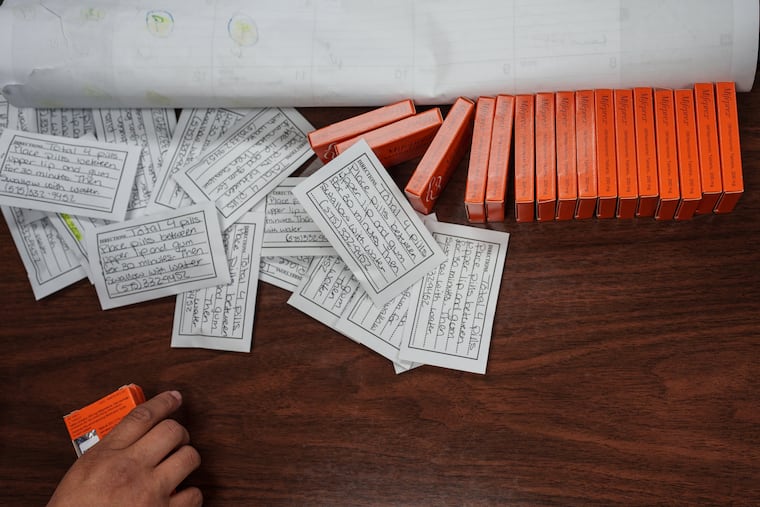

Clinics also were stocking up on mifepristone and preparing for the possibility of an increase in demand for procedure abortions, Perriera said.

An increase in procedure abortions would strain clinics already seeing more patients since the U.S. Supreme Court decision last summer, said Steinberg, CEO of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania, which operates clinics in Philadelphia and the surrounding counties.

Removing mifepristone from the market would create “unnecessary delays” to care for patients, if it takes longer for them to be seen by a doctor in person, she said.