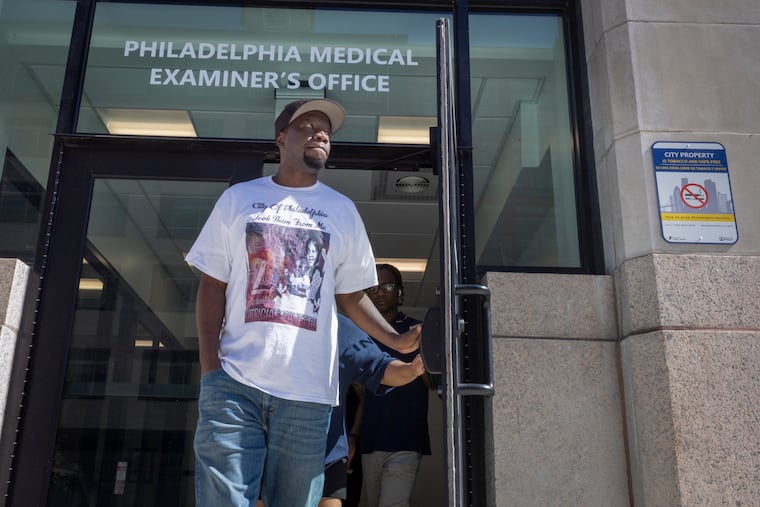

The brother of two MOVE victims finally got their remains back from the Medical Examiner’s Office

Katricia and Zanetta were 12 and 14 when police dropped a bomb on the Osage Avenue home, killing them along with nine others in the ensuing fire.

On Wednesday afternoon, in the quiet of a crematory chapel, Lionell Dotson clutched two tiny white boxes to his chest and wept.

Katricia Dotson, read the label on one. Zanetta Dotson, the other.

Inside were the remains of his sisters, who were 14 and 12 years old when both were killed in the MOVE bombing 37 years ago. For decades, Dotson, who was then 13, thought his family had laid them to rest. But a year ago, he learned that portions of the girls’ remains had never been buried — languishing in a box in the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office, forgotten on a shelf in a basement.

Dotson and his family wanted answers — only some of which they have gotten in the fallout over the scandal. But what they wanted most of all was to get his sisters home.

How his sisters’ bones ended up in a forgotten box — and how they were almost cremated at the order of former Health Commissioner Thomas Farley — has led to resignations, widespread outrage, and the city’s commissioning of a special independent investigation that issued a 257-page report in June chronicling failure after failure.

» READ MORE: Six key takeaways from the report on the mishandling of MOVE victims’ remains

On Wednesday, after a year of negotiation with the city, the Medical Examiner’s Office released the remains of Katricia and Zanetta to Dotson, who traveled with his family from North Carolina to receive the remains in person at the office. Afterward, they drove to a Mount Airy cemetery to cremate the remains, then flew home.

“Thirty-seven years in the making, and I got them,” Dotson said. “We’re going to leave behind the city that murdered them.”

The remains of Philadelphia’s deadly MOVE bombing

Lionell came to Philadelphia to claim what remains of his sisters with his wife, Tenee Dotson, three of their four children, and their 2-month-old grandson.

At the crematorium Wednesday, holding her grandson, Tenee, a Baltimore native, recalled her shock when Lionell first told her about his family.

“He said, ‘I had two sisters that died in a fire.’ And then he said it was a bomb,” she said. “I had never heard of [the MOVE bombing]. When he showed me, I thought: What happened? Who could do this?”

Dotson’s mother, Consuewella Dotson Africa, was a prominent member of MOVE, a Black liberation group with a back-to-nature message that squared off with police repeatedly.

Consuewella was imprisoned with eight other MOVE members in connection with a 1978 shootout that killed a Philadelphia police officer. Lionell’s grandmother took custody of him at 2 years old; the family tried to get custody of Katricia and Zanetta, but they stayed in the MOVE house in West Philadelphia, where Lionell said he often visited them.

Over the years, he has tried to piece together his sisters’ story, through his own vague memories and the stories his family told him. He knows Katricia was outspoken like him, determined and protective. “If you tried to bully someone, she’d say, ‘No, stop that, it’s wrong,’” Dotson said. “I mirror her in so many ways, but we never got to cross paths.”

On May 13,1985, after an hours-long standoff, police bombed the heavily fortified Osage Avenue house where MOVE was headquartered. Katricia, Zanetta, three other children, and six adults were killed. After police dropped the bomb, city officials let the fire burn, destroying blocks of rowhouses and displacing dozens of neighbors. No city official was ever criminally charged in the bombing.

» READ MORE: His sisters died in the MOVE bombing. Now, 37 years later, he’s still waiting to lay them to rest

Tenee had supported her husband as he reconnected with his mother and worked through feelings of abandonment he’d dealt with since childhood. Marrying and having his own children made him feel as if he was part of “a complete family,” she said. In the summers, they visited Consuewella in Philadelphia.

The tragedy of their past was always present — but the family believed the Dotson sisters had long since been laid to rest.

Then, last spring, the Dotsons learned that skeletal remains, likely Katricia’s, had been kept by University of Pennsylvania anthropologists since the investigation into the bombing and had even been used in online anthropology courses and seen by thousands of students without their consent.

A few weeks after the discovery, Farley, the city’s health commissioner, resigned after admitting that the city Medical Examiner’s Office also had a box of remains of MOVE victims — and that he had ordered them cremated when they were rediscovered in 2017. But a staffer at the office disobeyed the cremation order, and the box stayed there an additional five years, abandoned in a cold storage unit.

Just weeks after those revelations, Consuewella Dotson Africa died suddenly. Lionell Dotson has been fighting to regain his sisters’ remains ever since.

“[My mother] never got to see this come to an end,” he said Wednesday. “But I did. God kept me here for a reason.”

Identifying the remains

Daniel Hartstein, a lawyer representing the Dotson family, said that the Medical Examiner’s Office had reviewed records associated with the remains in the box as part of the city-commissioned investigation and identified them “as accurately as they could.” A spokesperson for the Philadelphia health department, which oversees the office, did not return a call for comment.

On Wednesday, the Dotsons met with the medical examiner and received a box containing his sisters’ remains. Dotson said an assistant medical examiner had apologized to him and his family before they left to take the remains to be cremated at Ivy Hill Cemetery in Mount Airy.

At Ivy Hill, the family briefly viewed the remains themselves. When the box was opened, Dotson fell to his knees.

Lionell has struggled, over the last year, imagining what remains had been kept at the Medical Examiner’s Office, and with his distrust of the city for what it had kept from him. “Now, that part is behind me. I physically saw it,” he said.

“[The remains] were small, small,” he said. “Things that shouldn’t have happened to a human.”

He said he was glad he’d seen them, though. Now, he could better understand what his sisters had gone through.

Afterward, Lionell and Tenee waited in another chapel as cemetery staffers cremated the remains. Lionell said he hoped that his mother and sisters would be proud of his efforts over the last year — and that Philadelphians remember the pain he has endured.

“Now [my sisters] can be out of the city of Philadelphia forever,” he said. What happened to them, though, “should resonate with the city of Philadelphia forever.”

» READ MORE: Philly’s medical examiner’s office is understaffed and struggling to investigate deaths. Fixing it might take years.

After an hour, a crematory staffer walked into the room with two white boxes. Lionell and his family got to their feet. As he signed a release form, he turned to his wife.

“Tenee, I’m doing it,” he said, almost in disbelief.

He turned to his children and thanked each one personally. He kissed his grandson’s head.

Then he looked down at the little white boxes.

“I got y’all. I’m gonna take care of y’all,” he said, tearing up. “Your little brother loves you.”