A dog disease resembling human multiple sclerosis may help treatment for both, Penn Vet study suggests

Similarity to a widely studied disease like MS could open the door to better diagnostic tests and treatments for the less-studied ailment in dogs—and may even yield a new tool to study human MS.

Seizures, vision problems, sluggishness, a strange head tilt — every year, veterinarians at Penn Vet encounter about a dozen dogs with these perplexing symptoms. By the time that owners notice this strange behavior, the dogs have already begun a mental decline, and one third soon die.

“That is in general something that’s frustrating about veterinary medicine,” said Molly Church, an assistant professor of pathobiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. “Dogs can’t tell you when they have a headache. They tend to present once the signs have gotten pretty severe.”

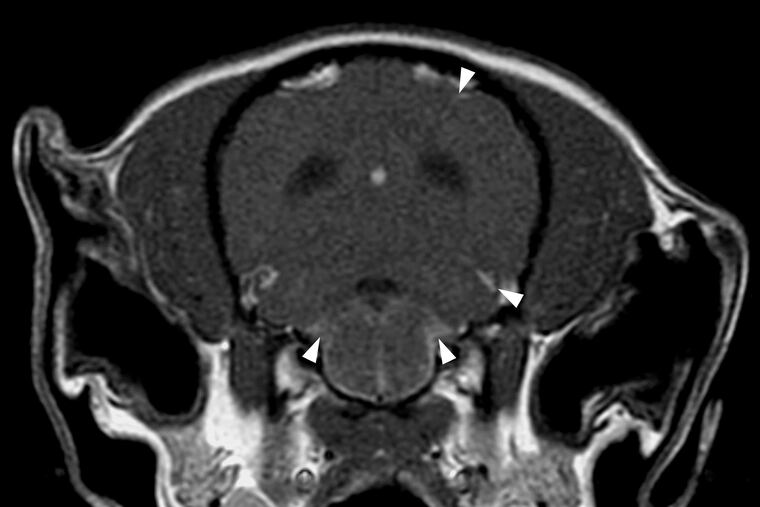

But when pathologists such as Church look at these dogs’ brains after death, they can easily spot the culprit: hordes of immune cells swarming the brain. In a study published this month, Church and collaborators at Penn Vet show that this condition—granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis, or GME—might resemble something more familiar to humans: multiple sclerosis.

Similarity to a widely studied disease such as MS could open the door to better diagnostic tests and treatments for the less-studied ailment in dogs — and may even yield a new tool to study human MS.

“We have this opportunity to not only help dogs and advance the therapeutics for this disease, but we might also learn something that might help humans,” Church said. “It’s one health. It’s helping all species.”

Humans and their canine companions have all kinds of similar diseases, such as cancer and diabetes. So when the Penn Vet researchers noticed that immune cells could attack the brains of both humans and dogs, they decided to take a closer look at MRI images and pieces of brain from 13 dogs that had died of GME to see whether anything resembled MS.

Something was out of place in the leptomeninges, a layer surrounding the brain. Specifically, there were groups of immune cells called B cells, which usually make molecules that sound an alarm to the immune system, or pick up debris from bacteria or fungi to put other immune cells on their scent. Packs of B cells also gather around the edges of the brain in human MS, where they pose a conundrum: No one knows exactly what they’re doing, but treatments that reduce B cells have been effective against some forms of MS.

“It’s something that is quite similar between the two diseases,” Church said. “It’s something that we could probe further in dogs to see if that can lend to finding an underlying process for GME.”

There are also other curious parallels. Both GME and MS tend to affect females, and diagnoses are more common in those who are younger.

But GME is not identical to MS, noted Jorge Alvarez, assistant professor of pathobiology at Penn Vet and senior author of the study.

The main hallmark of MS is the erosion of the protective coating around neurons, and that is only a side effect in GME. It also doesn’t appear to penetrate as deeply into the brain as expected in MS, said Abdolmohamad Rostami, professor and chairman of neurology at Thomas Jefferson University who was not involved in the study. But as in MS, the researchers found that injuries to neurons tended to happen in the parts of the brain underneath the B cell clusters.

No one had previously seen these B cells encircling the brain in GME, Alvarez said, and Church hopes this can improve early diagnosis of GME. Vets currently go down the list of usual suspects — cancer, infection, testable neurological conditions — and rule them out one by one until all that’s left is GME. Inspired by spinal tap tests for MS, Church’s follow-up studies have already shown that there are distinct molecular signatures of B cells in these dogs’ spinal fluid that could be a more accurate sign of GME.

“The ability to diagnose it a little earlier or to identify which dogs may respond better to a different therapeutic would be very advantageous for dogs,” Church said.

It could also inform more targeted treatments than current options, which are effective in only one third of dogs.

GME is typically treated with powerful drugs that dampen the dog’s immune system, such as corticosteroids, also used to treat human conditions with overblown immune responses such as allergies or even COVID-19. Even in humans, this is like “killing a fly with a sledgehammer,” Rostami said.

“If we find ways to target that inflammation in dogs, that could be translatable to humans not only with MS but maybe also other forms of inflammation that localize in these unique areas,” Alvarez said.

Rostami is eager to see what happens when dogs with GME are treated with the B cell-reducing drugs that some MS patients take. Like many MS researchers, he studies the disease in mice — or, at least, mice that have been given MS-like symptoms. B cells aren’t the root cause of this artificial disease, though, which makes it hard to study what B cells are doing in MS and why B cell treatments work so well.

“[GME] gives you a better model to study the B cell aspect of MS,” Rostami said.

Dog brains are bigger than mouse brains, so Rostami thinks it will be easier to see signs of disease. Alvarez also pointed out that because B cells are a sign of long-term disease progression in MS, longer-lived dogs may show signs of human disease better than short-lived mice.

As “man’s best friend,” dogs tend to live in similar environments as humans, unlike lab mice with carefully controlled cages and diets, Church said, so their immune systems interact with the same toxins and pathogens.

“The more you look into it, the more you realize that we really are similar,” Church said.