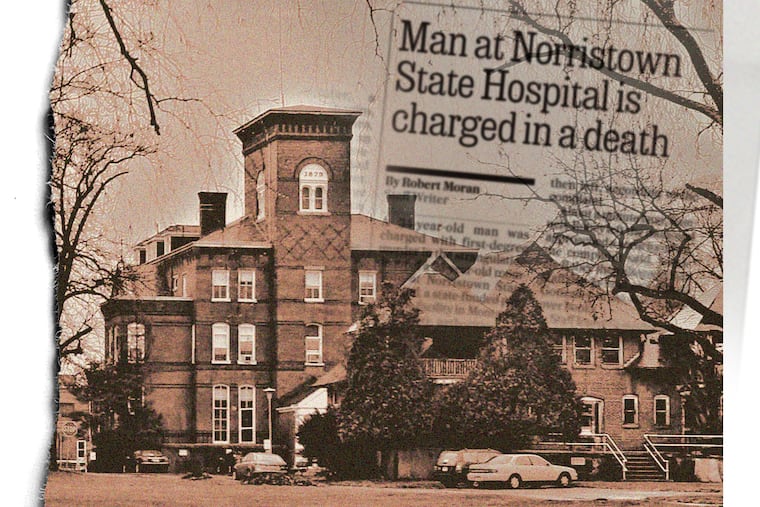

At Norristown State Hospital, police say one roommate murdered another. The facility failed both men, say families and inspectors.

Kyle Samuels-Robey has been charged with murder in the strangulation death of his former roommate, Jacob Gonzalez.

In his last phone call from Norristown State Hospital, Jacob Gonzalez spoke optimistically about his court hearing the next day, hoping a judge would clear him to leave the state-run psychiatric facility.

Before hanging up, he told his mother that he loved her. “I love you too, buddy,” she replied.

It was 6:30 p.m. By 9:30, he had been strangled.

In the hour before, Norristown staff signed off on paperwork indicating that every 15 minutes, they had gone into his room to check on the safety of Gonzalez and his roommate, Kyle Samuels-Robey, both diagnosed with serious mental illnesses.

But the staff had lied. No one visited the room between 8 and 9:15 p.m., video surveillance later revealed. The recording shows only one staffer looking into their room around 9:24.

Moments later, Samuels-Robey walked to the nurses’ station and asked for ice for his swollen hand. He said he had just “choked out” his roommate.

Gonzalez was found slumped over in his bed, unresponsive. Even then, no one immediately rushed to revive him.

» READ MORE: Man charged with killing roommate at Norristown State Hospital

These were among the security lapses identified by Pennsylvania Department of Health hospital inspectors in their investigation into Gonzalez’s July 14 death. Norristown received the state’s most serious safety citation, signaling concern that patients were unsafe.

In response, Norristown has suspended four workers and retrained its entire staff on responding to medical emergencies, state hospital inspection records show. The facility is run by a separate state agency, the Department of Human Services, which said in a statement that it “takes reports and complaints about the safety of individuals in licensed facilities seriously.”

DHS could not comment on specifics about Gonzalez’s and Samuels-Robey’s care because the case had been referred to law enforcement, a department spokesperson, Brandon Cwalina, said in a statement.

The terse hospital inspection report, publicly released in late August, states bluntly that the hospital “failed to maintain a safe setting for a patient.”

It details only the final, tragic ways in which Gonzalez and Samuels-Robey were both failed by a state-run institution charged with keeping them safe after they were found mentally incompetent to stand trial in criminal cases, both roommates’ families say.

A court ordered both men to receive treatment at Norristown, which was supposed to stabilize them enough for their criminal cases to proceed — or, failing that, to prepare them for transfer to another institution for care. But that is not what happened at the Montgomery County facility, where patients and staff have repeatedly reported rampant abuse.

Now, one roommate is dead, and the other is facing life in prison.

Gonzalez, 25, was committed to Norristown after breaking into the vestibule of a doctor’s office to stay warm on a November night. He had been living on the street, diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.

His mother, Tara Gonzalez, is still not sure what happened after her son hung up the phone on his last night. The state has told her only that her son died, and that it would pay for his funeral.

“This never should have happened,” she said. “These were people’s lives.”

At Norristown, Gonzalez was assigned to share a room with Samuels-Robey, 34, who had languished in state-run mental institutions for nearly a decade, diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Samuels-Robey’s track record of fighting with other patients had previously made him ineligible to have a roommate, his family told The Inquirer.

Samuels-Robey’s mother learned about the killing three days later, when television news reported that her son had been charged with murdering his roommate. Like Gonzalez’s mother, she was not informed by authorities of the hospital’s safety failings.

“This should never have happened,” said Samuels-Robey’s mother, Lenez O. Ward.

“I’m praying for whatever needs to be done to bring justice to this situation, for my son, for Jacob Gonzalez, and for every other person in the Norristown State Hospital.”

Troubles at a state-run hospital

Gonzalez’s death was not the first time that concerns have been raised about conditions at the 375-bed hospital, one of two in the state that accept people whom courts have deemed incompetent to stand trial.

The 144-year-old institution received a severe warning from the health department in 2018 after inspectors found that beds, doorknobs, shower grab bars, and other furnishings were not designed to prevent suicides by hanging, a serious safety issue in a psychiatric facility.

As part of the hospital’s correction plan, the fixtures were updated. During this time, nurses were required to check on patients every seven and a half minutes. Inspectors found the hospital had permitted checks to be made just twice or even only once an hour.

Two years ago, several current and former Norristown employees told The Inquirer that security staff frequently abused patients, egged them into outbursts and violent episodes, and engaged in cover-ups to protect themselves from retribution.

» READ MORE: They accused staff at a state mental hospital of abuse. But who would believe them?

More recently, state records show a high number of patient assaults in the forensic unit at Norristown, where Gonzalez and Samuels-Robey roomed together. It is designed to help patients recover from their mental illnesses so they can stand trial.

Norristown’s forensic unit filed 53 reports of patients assaulting other patients between November 2023 and April 2024, according to the most recent available state data. (State hospitals file a separate report for each patient involved in an assault, which means there are at least two reports for every incident.)

By comparison, the only other forensic unit in the state, at Torrance State Hospital outside Pittsburgh, reported one altercation in the same time period.

Gonzalez’s death triggered another state investigation at Norristown. This time, four staff members involved in the incident were suspended: two registered nurses and two security employees who perform basic nursing tasks and supervise patients.

Cwalina, the Department of Human Services spokesperson, declined to say whether the suspended staffers were disciplined or fired. He said he could not comment on specifics of Department of Health inspection reports.

“We work to ensure that any allegations and potential violations that put people at risk are investigated and handled urgently,” he said in a statement.

Gonzalez’s death was “a senseless tragedy,” said Brynne Madway, a staff attorney at Disability Rights Pennsylvania, which monitors violations of the rights of disabled people at state hospitals.

“It’s a failure of the state hospital’s most basic obligation, to provide care and treatment for patients in a safe environment,” she said.

Falsified paperwork and inadequate monitoring

State regulations detail exactly how Norristown patients should be watched: They must check on patients and complete a “patient accountability checklist” in black ink every 15 minutes.

State inspectors found that Norristown staff falsified the paperwork, claiming they had checked on Samuels-Robey and Gonzalez every 15 minutes between 8 and 9:15 p.m. on July 14.

Video surveillance showed no one had visited the room during that time.

Security footage showed that a staffer looked into the room at about 9:24 p.m. and left. Shortly after that, Samuels-Robey left the room, heading for the unit’s security desk.

Meanwhile, a forensic security employee walked into the room, turned the light on and off, and left again. The report does not say whether the employee saw Gonzalez in distress.

When Samuels-Robey told nurses he had hurt his roommate, the hospital’s staff did not respond urgently, video footage showed.

Workers came in and out of the room, at one point bringing a basket of medical supplies — but, crucially, not a crash cart with the lifesaving equipment used in medical emergencies, according to the inspection report.

Eventually, staffers did bring in a crash cart, which state policies require staff to do immediately when they find a patient unresponsive.

Even if the hospital’s workers could not have prevented Gonzalez’s death, they should have kept a closer watch on their patients, said Witold Walczak, the legal director of the ACLU of Pennsylvania.

“When you’re dealing with a high-risk population, you should not shirk your duties around status checks,” he said. “And you should never be falsifying records.”

In response to the health department citation, Norristown established a plan of correction that included retraining staff on emergency response protocol and conflict resolution, and agreed to have nurse managers monitor rounds to ensure patient checks were being done correctly, according to the inspection report.

The Department of Health continues to monitor the hospital’s efforts, said Cwalina, the DHS spokesperson.

‘A good-hearted person to his soul’

The Gonzalezes had hoped their son would receive care at Norristown.

Gonzalez had waited in jail for nearly a year for a bed to open up at Norristown after he was found incompetent in 2022 to stand trial for trespassing, his mother said.

» READ MORE: Determining whether people are mentally fit for trial in Pa. often traps them in the place making them worse: Jail

Gonzalez’s family had tried to get help for the former Scranton High School football player, who was diagnosed at age 21 with schizoaffective bipolar disorder, a condition marked by manic episodes, psychosis, and depression. But they struggled to find a program that accepted the family’s insurance.

“He was a good-hearted person to his soul,” said Tara Gonzalez, recalling how her son helped her take care of his five younger sisters and loved dancing and listening to music.

In the months he spent in jail waiting for a space to open at Norristown, Jacob Gonzalez refused medications. His mother could tell that his mental health was deteriorating.

When he finally began receiving treatment at Norristown, “he was back to looking like Jacob” on video calls with his parents, Tara Gonzalez said.

A long stint in psychiatric care

Samuels-Robey had been at Norristown for at least six years, having failed to convince the court of his competency at least 17 times, when he was assigned to room with Gonzalez.

Such a long stay at Norristown is unusual, said Walczak, the ACLU lawyer. Typically, a court will only spend a year deciding whether a patient is mentally competent to stand trial, he said.

Samuels-Robey’s family remembers him as a playful child with a bright smile and friends up and down his West Philadelphia block. At around 19 years old, his mental health declined, and he was eventually diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.

A string of arrests, beginning at age 20, led Samuels-Robey to Norristown. There was an assault charge for punching a police officer, and another charge of lying on a background check to buy a gun in 2011. He had written on the form that he had never been in a psychiatric hospital, according to police reports, when in fact he had spent time in a hospital ward for psychosis just a year before.

Samuels-Robey was eventually committed to Norristown’s forensic unit for treatment after being declared incompetent to stand trial on the gun charge.

For years, staff at Norristown had deemed him unable to live with roommates, relatives told The Inquirer, because he had been in several fights with patients and staffers. “He didn’t need to be with nobody the way he was coming at folks,” Ward said.

By 2024, Samuels-Robey was nearing the maximum number of years that, by law, he could have spent in the facility. In April, a judge ruled that it was unlikely he would recover sufficiently to stand trial.

He found the concept difficult to comprehend, his family said. He still spoke regularly about returning to his old block in West Philly, reconnecting with friends who had long since moved away, and going back to working at Walmart, as he had before his mental health and legal troubles began.

‘God, it hurts’

After the judge’s April ruling, the hospital had planned to release Samuels-Robey by October, his mother said. The man had been regularly taking his medications and cooperating with staff, his caretakers told his family.

His mother spoke with staff about transitioning him to a residential facility in Philadelphia, where he would live with a roommate.

The staff at Norristown felt Samuels-Robey was stable enough to live with another patient at the hospital until then, she said.

Still, she believed staff would monitor him closely and intervene if he became aggressive.

He had one other roommate before Gonzalez without problems, she was told.

After the July 14 killing, Samuels-Robey’s mother said, hospital staff told her family only that her son had been moved to a jail in Montgomery County after an incident occurred.

When she called Samuels-Robey’s father, he told her he had just seen a news report that their son had been charged with murder. “It hurts,” Ward said of thinking he was accused of killing another mother’s son. “God, it hurts.”

The family of his slain roommate is angry that Norristown failed to protect their child.

“I’m just furious, and I’m even more mad knowing the hospital lied,” Tara Gonzalez said. “I wanted Jacob to get through this, to be on the other side. I’m so mad he never got to.”