These obese mice lost weight by ‘sweating’ their fat, Penn team finds

The animals lost weight despite eating more. But would it work in humans?

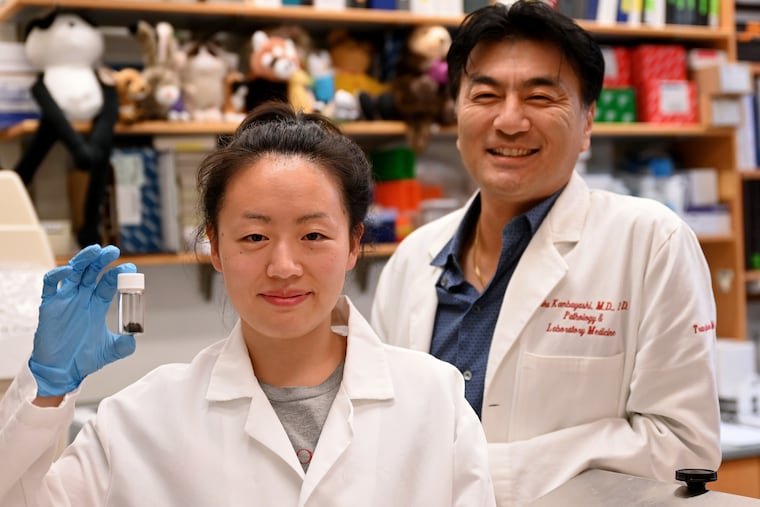

In search of better treatments for type 2 diabetes and other consequences of obesity, Taku Kambayashi has long wondered if he could harness a bodily function that most people think about in a very different context: the immune system. There was evidence to suggest this approach might work, as certain types of immune cells were known to play a role in metabolism.

But when he and University of Pennsylvania colleagues stimulated these cells in a series of experiments on obese mice, they got a surprise. Not only did the animals become healthier in terms of their blood-glucose levels and other metabolic “markers,” they also lost dramatic amounts of weight.

Within four weeks of triggering the animals’ immune response, Kambayashi and graduate student Ruth Choa found the mice had lost 40% of their body weight, on average. All of it was in the form of fat.

What’s more, careful measurements revealed that the animals’ weight loss was not the result of burning calories any faster or eating less food. They actually were eating even more than before. The real answer, the scientists reported Thursday in Science after many months of detective work, was that the mice were “sweating” out fatty molecules through their skin.

“It’s wild,” said Kambayashi, an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

The zillion-dollar question is, of course, whether this phenomenon could be exploited in humans. For the moment, the answer is unclear, and all the usual caveats apply. Mice are not humans. All sorts of cures for cancer and other ills have seemed promising in lab animals, only to wash out when tried in people.

Still, humans are known to secrete fatty molecules through the skin, just like the mice — though at low levels. The oily substance is called sebum, produced by the sebaceous glands and found on the skin and hair. (It’s separate from sweat; Kambayashi used that term in his paper just to get the idea across for a general audience.)

» READ MORE: Meet the Philly kid who helped solve the strange case of a missing bee and a rare Pa. plant

A typical person secretes 130 calories worth of sebum per day — not enough to have an impact on body weight. But if that process could be accelerated, say, fourfold, Kambayashi thinks he would be onto something.

“You’d lose a pound of fat per week,” he said.

Some others in the field are taking a wait-and-see stance, as obesity is a complex disorder. Among them is Richard Locksley, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies the same kinds of immune cells.

“It’s early days, but it’s interesting and plausible,” he said.

The Penn scientists stimulated the mouse immune cells by treating them with a type of cytokine — from the same family of proteins involved in a harmful inflammatory overreaction to COVID-19, called a “cytokine storm.” The scientists coaxed the animals to produce the cytokine by injecting them with a viral vector, loaded with genetic instructions to make the protein — much like the COVID-19 vaccine made by Johnson & Johnson.

If the concept were to be explored in people, researchers likely would try to achieve the same goal — ramping up production of this cytokine, called TSLP — by administering a drug instead of genetic instructions, he said.

Researchers already are testing drugs that accomplish the opposite objective, interfering with TSLP, as a possible treatment for atopic dermatitis. Commonly called eczema, the skin condition is triggered by an overreaction by the immune system.

Ramping up TSLP, on the other hand, would have to be done carefully, lest it result in an inappropriate immune response. Kambayashi already is laying the groundwork for follow-up studies in people.

» READ MORE: Temple research finds that tweaking CBD may help it curb pain and opioid use in mice

For the findings published Thursday, the bulk of the lab work was performed by Choa, who earned her Ph.D. in 2020 and is now in the midst of finishing her M.D. at Perelman, Kambayashi said.

“She did easily the work of three people in a year and a half,” he said. “She was on a mission.”

Among the remaining questions is just how the cytokine results in excess secretion of sebum. The researchers found that TSLP causes certain kinds of immune T-cells to migrate to the sebaceous glands, which in turn somehow results in more secretions.

No matter the outcome of these studies, Kambayashi said that in hindsight, it makes sense that obesity might be addressed via the immune system.

As physicians have reminded us during the COVID-19 pandemic, obesity often is accompanied by a chronic level of immune-related inflammation. Excess adipose tissue acts as a type of “organ,” releasing hormones and other chemicals that place the body in a chronic state of low-level stress, placing the person at higher risk in the event of infection.

Still, the weight loss in the mice was a surprise, to the point Kambayashi thought something must have gone wrong.

“I thought they were sick, that they just weren’t eating,” he said.

But in fact, they were eating more than mice in a control group, which had not been been treated with the cytokine.

The key clue came with a curious phenomenon that Kambayashi and others had ignored in the past: Mice treated with TSLP were known to develop a shiny coat of fur.

He and Choa noticed that the same was true with these mice. So they shaved the animals’ fur, analyzed it, and discovered it was rich in calorie-dense, fatty molecules called wax esters.

Would humans sign up for that kind of treatment, knowing it would increase the secretion of oily fats through the skin? Among possible drawbacks: Excess sebum is associated with the teenage scourge of acne.

Still, with obesity among the leading health problems in the United States, millions remain eager to try new solutions. Kambayashi says he’s determined to give them the chance.