Fentanyl is soaring in Pennsylvania’s drug market in 2022, AG report finds

The report was released as the state House Judiciary Committee is set to vote on a bill that would legalize the possession of fentanyl testing strips for personal use.

In the first three months of 2022, the Pennsylvania attorney general’s narcotics investigators seized more fentanyl than in the entirety of 2021, an indication of the exploding crisis around the synthetic opioid increasingly fueling overdoses across the state.

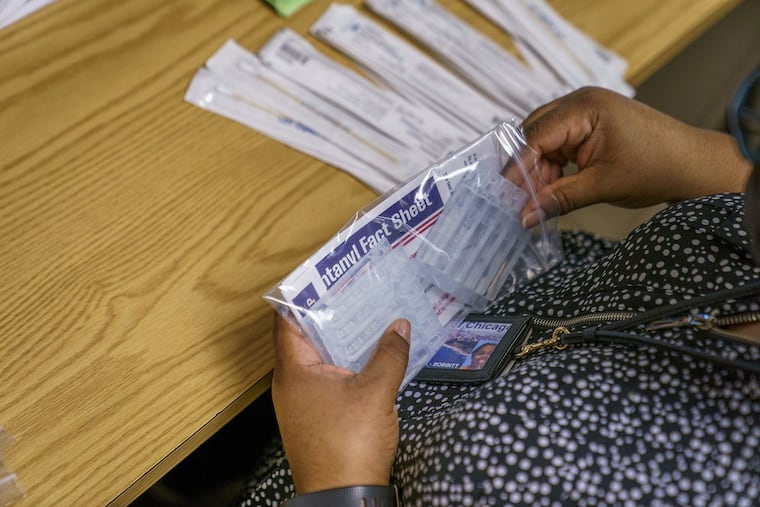

A new agency report detailed the skyrocketing impact of fentanyl ahead of a vote on Tuesday by the state House Judiciary Committee on a bill that would make it legal for individuals to use fentanyl testing strips. These can help drug users determine whether fentanyl is in the drugs they’re about to consume — a crucial overdose prevention tool, especially for people who aren’t used to taking opioids. The bill passed unanimously out of committee; it will now go to the full House for a final vote.

“The longer we delay in legalizing, the more lives will be lost,” said State Rep. Jim Struzzi (R., Indiana).

Though some jurisdictions in Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia, do not arrest people for using fentanyl testing strips, they’re still technically illegal statewide, just like syringe exchange programs that encourage injection drug users to swap out contaminated needles for clean ones as a way to reduce skin infections and the spread of bloodborne diseases.

Fentanyl is significantly more powerful than heroin and can be produced in a lab, which means it’s easier to manufacture and distribute. Its potency also makes it deadlier — especially for people who do not know that it’s present in their drugs.

Thousands of Pennsylvanians died of overdoses in 2021 mostly fueled by fentanyl. Overdose deaths spiked by 16.4% in the state in 2020, and increased again by 6% in 2021, with 5,438 deaths reported that year, according to the report.

The attorney general’s Bureau of Narcotics Investigation seized more than 59,000 grams (or about 130 pounds) in the first three months of 2022, compared with about 56,000 grams (around 123 pounds) in the entire previous year.

And in that same time period, the office seized twice the amount of fentanyl than it did of heroin in 2021, and 40 times the amount of fentanyl vs. heroin in just the first three months of 2022, according to the report.

In Philadelphia, fentanyl has replaced most of the city’s heroin, and many opioid users are used to or even prefer fentanyl. But it’s also contaminated cocaine and methamphetamine, causing overdoses in drug users who have no tolerance for opioids, and is increasingly being sold in counterfeit pharmaceutical pills, which some drug users seek out because they believe, often falsely, that such pills are legitimately manufactured and safer to use.

The report also noted increases in fentanyl seizures among Philadelphia’s Drug Enforcement Authority field division, and increases in the prevalence of fentanyl in drugs tested by the Philadelphia Police Department. Xylazine, an animal tranquilizer that’s increasingly turning up in Philadelphia’s fentanyl supply, is also of concern in the region, the report said.

“Fentanyl is increasingly mixed with other illicit drugs to increase the potency, at a cheaper cost,” the report read.

At the state House Judiciary Committee, Rep. Emily Kincaid (D., Allegheny) voted for the bill but suggested it be amended before the final vote to make it clear that outreach workers who serve people with addiction will also not be prosecuted for distributing fentanyl test strips.

“I’m extremely supportive of this bill,” she said. “My concern is that with the language of the bill — that we may be setting up a scenario where these strips are legal but inaccessible to people because distributor organizations may be unwilling to provide them because they are not using those strips for their own personal use.”