The opioid crisis has tripled deaths among Philly’s homeless population in the last decade

Most deaths in the city’s homeless population were due to overdoses, a sea change from just a few years ago.

Philadelphia’s opioid overdose crisis — the worst of any big city in the nation — is contributing to skyrocketing death rates among people experiencing homelessness, new data released Wednesday show.

Such deaths tripled in the last nine years, the Office of Homeless Services wrote in a news release, from 43 in 2009 to 132 in 2018.

The number of deaths in the homeless population in 2019 hasn’t yet been confirmed, but will likely be only slightly less than in 2018, said Liz Hersh, director of the Office of Homeless Services.

And most deaths in the city’s homeless population were due to overdoses, Hersh said. That’s a sea change from just a few years ago. Between 2009 and 2015, about 37% of deaths among the homeless population were from overdoses. Between 2016 and 2018, overdoses accounted for 59% of such deaths.

Nearly all of the fatal overdoses among homeless people in 2018 involved opioids, with the deadly synthetic opioid fentanyl present in nearly three-quarters of the deaths.

In general, officials said, people experiencing homelessness are far more likely than others to die of overdoses.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s annual homeless count reveals new realities about the opioid crisis

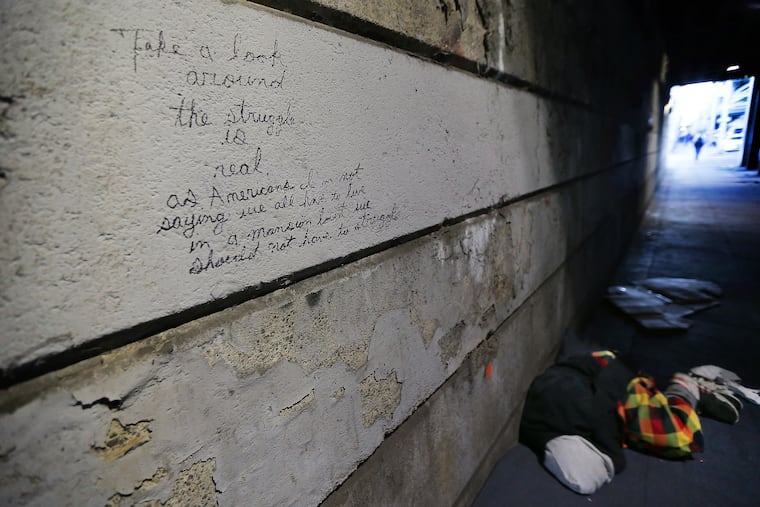

“I think we knew it was bad, but seeing the numbers in such stark relief, it took my breath away,” Hersh said. “It’s really been this perfect storm of the increased homelessness with the opioid crisis. And the people who are really suffering the most and have been hardest hit are the people who started out with the least.”

As the region’s opioid crisis has worsened, more people have begun to live on the streets of Philadelphia. In the summer of 2018, a citywide count revealed that the homeless population in Kensington, the heart of Philadelphia’s opioid epidemic, had more than doubled. More than half the city’s homeless population was concentrated in the neighborhood.

In January 2019, another count showed that the city’s homeless population had increased by about 5% from the year before, which officials took as an encouraging sign that efforts to get people inside were working. Opening low-barrier shelters that don’t require sobriety and making it easier to access addiction treatment and permanent housing have helped, Hersh said.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia’s Kensington ‘under siege’ as opioid-linked homelessness soars

“But we have to be even more aggressive, diligent, and vigilant in those efforts,” she said. “These are people. They’re not less than anyone else. They’re just people in an unfortunate situation, and it’s not right to write them off.”