Overdose deaths by zip code: Philly’s crisis expands outside of Kensington with rising deaths in North and Southwest neighborhoods

An Inquirer analysis of overdose deaths by zip code shows how the crisis has shifted between neighborhoods over the last five years.

Fatimah Hatton last saw her mother in early March 2021, when she left her home in North Philadelphia to stay with friends. For five days, her mother sent text messages begging her to return, but the 16-year-old with a bright smile and quirky fashion sense responded that she just wanted to have fun.

She never came home. In the early hours of the morning on March 9, Fatimah overdosed on a fake pharmaceutical painkiller laced with the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl. She was one of 1,276 people who died after overdosing in Philadelphia in 2021.

She had never used drugs before, according to her mother, Nafeesah Sawyer. Neither she nor her daughter, Sawyer said, had known much about the dangers of fentanyl — like many of their neighbors in the 19132 zip code that includes neighborhoods such as Strawberry Mansion and Swampoodle.

The city’s overdose crisis is now at their doorsteps. Drug-related deaths in these communities have risen by 48% in five years, reflecting how the toll has shifted between neighborhoods.

An Inquirer analysis of overdose deaths by zip code shows deaths increasing in North Philadelphia and Southwest Philadelphia in response to changing demographics. Overdose deaths among Black and Hispanic people in the city have steadily risen over the last several years, as deaths among white residents have dropped.

“It may be less of a question about what’s going on with those neighborhoods in particular, and more of the demographic that live in these zip codes, which are mostly African American or people of color,” Deputy Commissioner of Health Frank Franklin said.

Kensington, where public dealing and open injection of opioids are common, still sees the highest numbers of overdose deaths in the city: 209 people died there in 2017. The scope of its crisis has fluctuated from year to year. In 2021, the last year for which complete data are available,169 people died in the neighborhood, a 19% drop from 2017.

In the same time frame, deaths increased steadily in several other neighborhoods that previously saw few overdoses.

In Southwest Philadelphia’s 19143 zip code, which includes Kingsessing, fatal overdoses nearly doubled in five years, from 22 to 42.

In North Philadelphia, deaths increased by 48% in the 19132 zip code between 2017 and 2021, from 35 to 52 deaths. Overdose deaths increased by 61% in neighboring 19140, an area including neighborhoods like Hunting Park, Tioga, and Nicetown, where 84 people died in 2021.

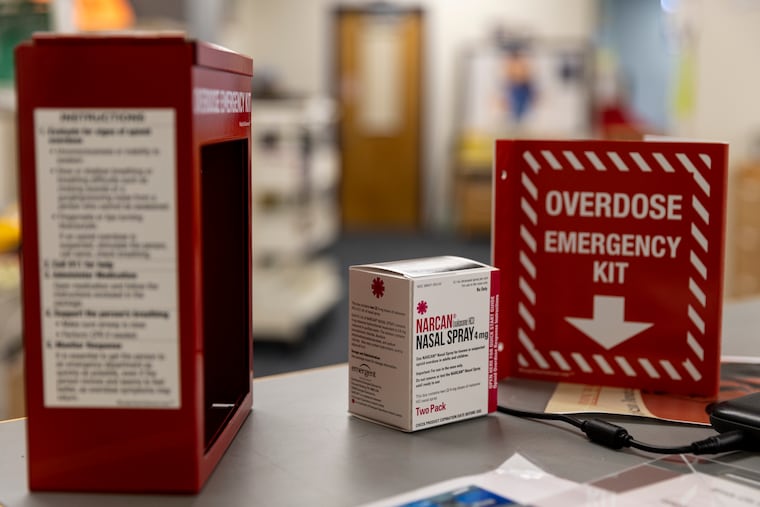

Dominique McQuade is part of a city health outreach team that conducts weekly outreach in 19140, passing out the overdose-reversing drug naloxone and street tests that allow people to check their drugs for fentanyl.

Recently, McQuade said, two people the team worked with regularly died from drug use. “It’s hard. It feels like you’re not doing enough,” she said.

Many of the people she works with typically use stimulants — and tend to believe they’re not at risk for an overdose because they don’t use opioids. But because their tolerance for opioids is low, if their drugs are unknowingly laced with fentanyl, their likelihood of dying is even higher.

“People are dying in their homes,” she said. “They don’t know how to react.”

Some of the neighbors McQuade talks with feel numb in the wake of a friend or family member’s overdose death, she said. She and her colleagues try to give them space to grieve. “It’s about making people feel seen, letting them feel the grief, just giving them someone to cry with,” she said.

Raising awareness

Fatimah’s mother said her daughter died at a time when the teenager was carrying a heavy emotional load: caring for an infant, while also grieving the death of her father a year before. Though she doted on her 10-month-old son, Zaid, she was battling postpartum depression and felt isolated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Sawyer recalls the five days of panic when her daughter did not come home, and the shock and grief that followed. It’s a story that she now shares to bring awareness to her neighbors and friends.

Since her daughter’s death, Sawyer regularly posts on social media about the dangers of fentanyl, and has attended rallies in Washington to raise awareness about the contamination of the drug supply.

She clings to good memories of her daughter. How Fatimah held her mother’s hand crossing the road until she was 12. How she loved animals and dreamed of being a veterinarian. How much she loved her son, now 3 and being raised by Sawyer: “She was taking parenting classes on her own, she wanted to get a job — everything was about him.”

More days than not, Sawyer posts a photo of her daughter on her social media. She always includes the same caption.

“She was a mother. She was a daughter. She was an aunt. She was a cousin. She is missed. She is deeply loved.”