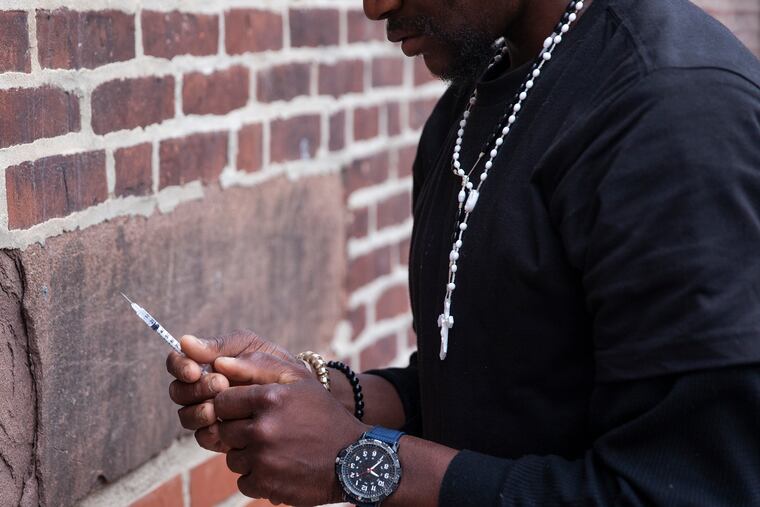

Philadelphia’s drug pandemic, like COVID-19, now puts the heaviest burden on Black residents, data show

Health officials said Wednesday that they are developing an overdose awareness campaign “that considers the diversity of people who use drugs and Philadelphia’s rapidly changing drug market.”

During the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, drug overdoses killed more Black Philadelphians than white ones, a demographic shift that echoes the health disparities made visible during the pandemic.

Overall, overdose death numbers in Philadelphia are about the same as at this time last year, according to data released by the city Public Health Department on Wednesday. But between March 23, the day Philadelphia’s lockdown started, and June 30, 147 Black residents died of overdoses, compared with 119 overdose deaths among white residents and 47 among Hispanic residents.

Non-fatal overdoses have also increased among Black residents, health officials said.

Though overdoses have been increasing among people of color in Philadelphia for some time, the demographic shift that took place during the pandemic is unprecedented, health officials said. Throughout the opioid crisis, most of the city’s fatal overdose victims have been white.

“Since 2010, at least 2010, the majority of people overdosing in a given three-month period have been non-Hispanic white,” said Kendra Viner, the opioid program manager at the city health department. “We certainly have seen, in the last couple years, a trend toward more non-Hispanic Blacks dying of overdose and also non-fatally overdosing. But that trend took a steep incline in the few months after the stay-at-home order.”

The rate at which white Philadelphians die of overdoses has been dropping for two years — even as overdose death rates among Black and Hispanic residents have risen.

Numerous factors could be at play, experts say, ranging from changes in the drug supply to the far-reaching impact of systemic racism. Fentanyl, the powerful synthetic opioid that has tainted much of the city’s heroin supply, is behind most overdose deaths in the city, and in recent years the drug has begun to make its way into stimulants like cocaine. Cocaine-related deaths, health officials say, have historically been more common among Black and Hispanic Philadelphians; now, members of those communities are dying with both fentanyl and cocaine in their systems.

Nationally, Black patients face significant barriers in entering addiction treatment, studies show. Among patients with Medicaid, whites are more likely to receive the popular opioid addiction treatment drug buprenorphine. Black overdose victims are less likely than whites to receive follow-up care from an emergency room, even with private insurance.

Yet national surveys suggest white patients are only slightly more likely than black patients to use heroin, or to take prescription opioid pills without a doctor’s direction.

“For the longest time, even though the numbers showed a predominance in white non-Hispanic people [dying of overdoses], we all knew that vulnerabilities existed among other populations,” said Priya Mammen, an emergency physician and public health advocate who also is co-chair of the community advisory board for the city Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbilities.

Now, she said, COVID-19 is revealing racial inequities in the health-care system and many other aspects of American life more clearly than ever before.

Across the country, Black and Hispanic communities have been hit disproportionately by COVID-19 illnesses and deaths — as well as the unemployment brought on by lockdowns.

Philadelphia health officials say they’re worried about a possible link between unemployment and overdoses, especially among Black Philadelphians. They noted on Wednesday that 48% of Black overdose victims in the second quarter of 2020 — the period when the lockdown began — were unemployed. That’s up from 32% before the pandemic.

By contrast, unemployment rates among white and Hispanic overdose victims were mostly stable before and after the pandemic began.

“The people who are driving that ... demographic change in overdose deaths — it’s associated with their lack of employment,” said James Garrow, a spokesperson for the health department. “The only thing that’s really changed between Quarter 1 and Quarter 2 is the pandemic.”

Health officials said Wednesday that they are developing an overdose awareness campaign “that considers the diversity of people who use drugs and Philadelphia’s rapidly changing drug market.”

“It’s a huge wake-up call to us — what it shows us is that a lot of the education work we’ve done has been focused on the [Philadelphia] population as a whole. Some of the way that we’re messaging, and the way we’re distributing messages, may not be adequately reaching some of these other minority populations,” Viner said.

For example, she said, surveys conducted after the city’s last campaign urging citizens to carry naloxone, the overdose reversing drug, were less likely to be seen by Black Philadelphians — who were also less likely to carry naloxone themselves.

Anecdotally, she said, Black drug users have told the health department in focus groups that they sometimes are afraid to carry naloxone. They worry that if they’re stopped by police, they will be penalized for drug use or mistaken for a drug dealer.

Mammen said it’s key that outreach around drug use, and drug treatment itself, is tailored to specific needs.

“One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to drug treatment, and one size doesn’t fit all when it comes to messages,” she said.

The full picture of how the pandemic has affected drug use and fatal overdose has yet to emerge. But preliminary information indicates overdoses in general have been rising in communities around the country, including some in Pennsylvania.

The data released by the city health department Wednesday shows paramedics responded to more overdoses after the city locked down in March: Weekly average calls for overdoses or drug poisonings increased from 263 to 275.

Yet slightly fewer people visited emergency rooms for overdoses during the pandemic: The city averaged 123 ER visits for overdoses a week before the city’s stay-at-home order went into effect, and 118 visits a week afterward.

ER visits for people seeking help with withdrawal symptoms also decreased. Those visits have since inched back up since the city began to ease lockdown restrictions, health officials said.