Political furor over ‘crack pipes’ could harm efforts to stem drug deaths, advocates fear

“They’re hurting their constituents. They’re stigmatizing harm reduction. These are health interventions we know actually save lives and are evidence based,” said one advocate.

A conservative furor over a federal grant to help address the nation’s skyrocketing overdose death toll now has advocates concerned it could harm public health services for people with addiction.

Last week, conservatives seized on a single line in a $30 million package for organizations that help prevent disease, injury, and death in people with addiction.

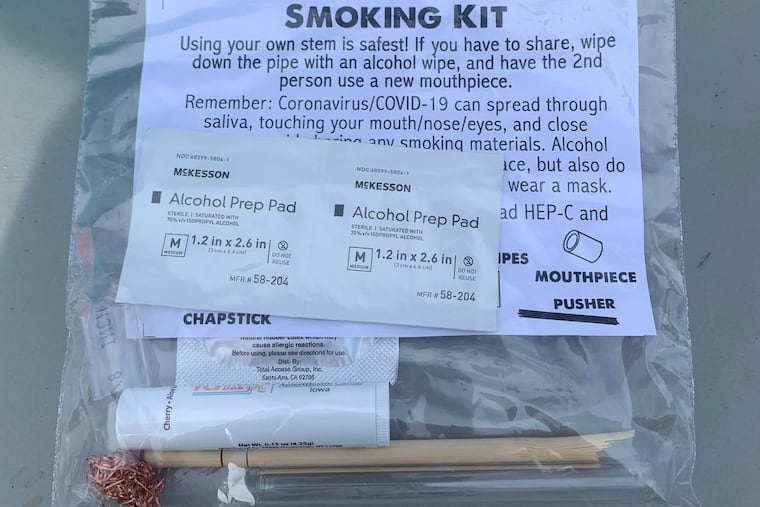

Some of the money was to be available for syringes and “safer smoking kits” for people who smoke illicit drugs such as crack and meth. Contaminated paraphernalia itself can promote disease and injury, so a central tenet of “harm reduction” efforts is to help people who are not ready to stop using drugs at least avoid additional risks. Smoking kits mostly include sanitary tools like alcohol wipes and rubber mouthpieces; sometimes they include a glass pipe itself.

Conservative media outlets had a field day, with headlines both catchy and misleading: “Uncle Sam to Hand Out Crack Pipes,” one Fox News chyron blared. The Biden administration scrambled to assure the public that it wasn’t spending funds on pipes, but the outrage roared on.

This week a Republican senator threatened to force a government shutdown over funding for harm-reduction organizations. Several other Republican lawmakers (and one Democrat, West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin) have introduced bills to ban federal dollars from going toward smoking paraphernalia and sterile syringes.

Meanwhile, harm-reduction advocates point to last year’s record drug toll of more than 100,000 deaths nationally and worry that the misinformation will make it even harder to reach people in addiction with lifesaving services. In 2020, Philadelphia saw 1,214 overdose deaths; the 2021 data are not yet available.

“They’re hurting their constituents. They’re stigmatizing harm reduction. These are health interventions we know actually save lives and are evidence-based,” said Maritza Perez, the director of the office of national affairs for the Drug Policy Alliance, a national harm-reduction nonprofit.

“What’s been most damaging has been the misinformation spread around what harm reduction is, generally. They’re making it seem like giving people drug paraphernalia is using taxpayer dollars to support drug habits, without really engaging in a conversation around the fact that these are evidence-based health services.”

Manchin’s bill, cosponsored by Sen. Marco Rubio (R., Fla.), would ban the federal government from funding any kind of paraphernalia for smoking or snorting drugs. The bill would also restrict the federal government from paying for clean syringes, except in areas experiencing or at risk for increased HIV or hepatitis C outbreaks from injection drugs.

(Typically, federal funds can support the operation of syringe exchanges but cannot pay for syringes themselves. The new harm-reduction funds from the Biden administration were not subject to that ban.)

When the Biden administration first announced the grant funding, harm reductionists were elated.

“Harm-reduction funding at that level is unheard of,” said Jim Duffy, the founder of Smoke Works, a Boston-based company that supplies pipes at reduced costs to harm-reduction organizations. “People in the community did a little jig when that money was announced. They were scrambling to write the grants — and some wrote in plans for safer smoking materials, to widen the audiences their harm-reduction reached.”

Decades of evidence shows that harm-reduction tactics like syringe exchanges can decrease bloodborne infection rates and connect drug users to treatment and other resources. But they’ve long been stereotyped as enabling drug use, and many harm-reduction organizations operate on shoestring budgets, sometimes in states that have explicitly outlawed their work.

Advocates say handing out pipes is a crucial — and often overlooked — tool to reach more drug users.

“People weren’t used to it at first — pretty much all you ever got handed were clean syringes,” said Adrienne Standley, who does outreach work around safer drug use with the Philadelphia advocacy organization SOL Collective.

“People had been using super old, super broken pipes that were being shared around. [Handing out pipes] was a great way to engage people — especially people who were only using crack or meth, who you might not have been able to talk to otherwise. From there, you can get them Narcan, and any other safer use supplies they might need. The conversation opens up so much.”

Narcan, the opioid-overdose-reversal drug, once wasn’t thought of as crucial for cocaine users. But now fentanyl — the powerful synthetic opioid that has replaced most of Philadelphia’s heroin supply — is making its way into other drugs including cocaine, Standley said.

Jenna Mellor, the executive director of the New Jersey Harm Reduction Coalition, sees in the pipe uproar more than stigma against those in addiction.

“The outcry about pipes was clearly rooted in anti-Black racism, and the long history of using moral panic about crack cocaine to target Black people and police Black communities,” she said. “We should have had a harm-reduction approach to crack cocaine since the 1980s.”

Black drug users are slightly more likely than whites or Hispanics to report using crack, a smokable form of cocaine that has the same molecular structure. But sentencing laws for crack dealing and use are significantly higher than for powder cocaine, and Black people have been disproportionately imprisoned on such charges for decades.

SOL Collective hands out about 140 pipes per week as part of safer smoking kits and gets pipes in part from Smoke Works.

Duffy knows well what safer smoking kits could mean to a person who needs help. Now in recovery, he was addicted to meth for years. “I was a meth smoker, and the only time I ever injected was when there was no pipe available,” he said.

“The folks I [used] with would get needles from the exchange — and I was like, ‘I would never go there.’ I didn’t need needles — I needed a pipe. But had the exchange had something to offer a non-injection drug user, who knows what other services I would have taken advantage of.”