An old idea from a German Jewish scientist spared by the Nazis is getting new life: Prevent and treat cancer by cutting out sugar

Cancer is a disease governed by genetic mutations, and fueled by sugar.

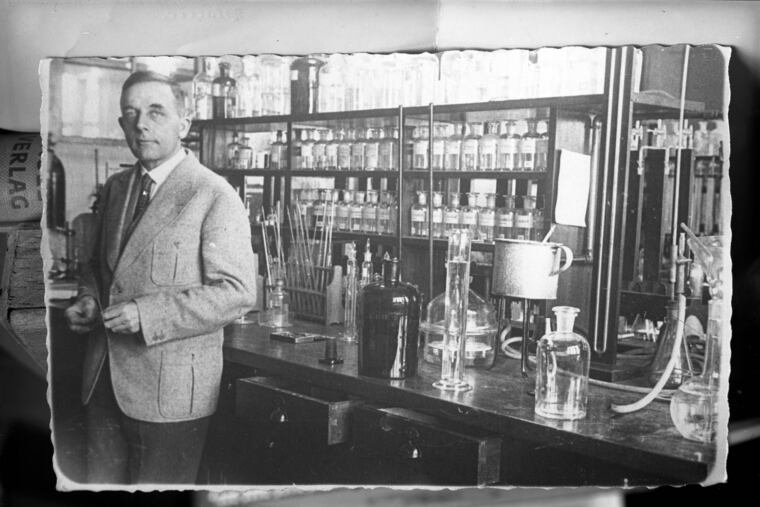

Otto Warburg probably would have been sent to a concentration camp if the Nazis weren’t hoping he could cure cancer.

Warburg was a Jewish gay man living openly in Berlin with his partner as Hitler rose to power. Warburg was also a biochemist, as brilliant as he was arrogant. In the 1920s, he discovered a hallmark of cancer, now called “the Warburg effect.” Malignant cells are ravenous for glucose, or blood sugar, consuming 10 times more than healthy cells. He dedicated his career to studying this strange metabolic anomaly because he believed it was the root cause of cancer.

He won the 1931 Nobel Prize for his work. But it was mostly forgotten by the 1950s, eclipsed by the molecular genetics revolution that set off a search for mutated, cancer-causing genes. He died in 1970 at age 86.

The rise, fall, and recent resurgence of research into cellular metabolism is the subject of Ravenous: Otto Warburg, the Nazis, and the Search for the Cancer-Diet Connection. Author Sam Apple, a journalist based in the Philadelphia suburb of Wyndmoor, weaves together this complex narrative in a way that makes arcane science accessible and fascinating.

The book is also thought-provoking for anyone interested in avoiding cancer — and who isn’t?

“It’s not obvious to me that there would be a breakthrough cancer therapy” if Warburg’s focus on cellular metabolism had not been shunted aside, Apple said in a recent interview. “More likely, there would have been more attention to the relationship between our diets and the metabolism of the whole body and cancer. I think this could have had a dramatic impact on cancer prevention. But the link is still is not widely appreciated.”

A defect, or an edge

Otto Warburg was related to a wealthy German Jewish clan of bankers, scholars, and influencers. He was groomed for scientific greatness by his father, Emil Warburg, a leading physicist of the time.

The pinnacle of Otto Warburg’s career happened to coincide with the rise of the Third Reich. When Warburg refused to sign a “declaration of Aryan descent,” the Nazi customs official tasked with asking Warburg to lie endeavored to get him punished by the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, the parent organization of Warburg’s scientific institute.

Warburg not only managed to get off scot free, but he also asked the Wilhelm Society president to ask the Reich Ministry of Finance to rewrite racial decrees so that non-Aryan institute directors would be “treated like Aryan directors.”

“In 1934, at a moment when Hitler had already begun sending Germans to concentration camps, Otto Warburg, a gay man of Jewish descent, wanted Nazi laws rewritten according to his personal needs,” Apple writes in the book.

As the author explains, cancer rates were inexplicably rising in Germany and other developed countries, and the Nazis’ fear of the disease ran almost as deep as their anti-Semitism and homophobia They despised Warburg, but needed his scientific genius.

Warburg invented several new tools to study the metabolism of cells, including the manometer, an instrument used to measure the force exerted by a gas or liquid.

He knew that in a healthy cell, blood glucose was normally converted to energy in a process using oxygen. This process, which involves enzymes that Warburg spent years identifying, occurs in the cells’ power stations, now known as mitochondria.

He discovered, to his amazement, that cancer cells broke all the metabolic norms. In addition to overconsuming glucose, the cells turned it into energy using an inefficient process that did not require oxygen — even though plenty of oxygen was available.

“The cancer cells were chopping glucose molecules in half and spitting the fragments right back out of the cell,” Apple writes in an elegantly simple description of anaerobic glycolysis, or fermentation, the biochemical process that also gives us beer and wine. “Cancer cells, Warburg realized, were fermenting glucose just as simple organisms like yeast and bacteria do.”

But why? Warburg hypothesized — more like proclaimed — that cancer cells’ mitochondria were somehow defective, so the cells had to resort to a backup power generator, namely fermentation.

Today, while the search for answers continues, the evidence suggests that fermentation is not a response to a defect. Rather, it gives malignant cells an advantage as they turn into uncontrollable, immortal renegades.

“Glucose molecules are the building blocks that cancer needs to create daughter cells,” Apple boiled it down during the interview. “The most influential scientists now think it’s about the cancer cells’ bioenergetic needs.”

A concept comes of age

Following the 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA — the genetic instructions for everything cells do — oncology researchers became focused on finding and fixing the defective genes that give rise to cancer.

In that postwar era, Warburg’s focus on cell metabolism was seen as outmoded, like studying the fuel line in hopes of understanding a high-tech engine.

Beginning in the 1990s, however, some leading researchers realized that certain cancer-causing genes known for their role in cell division also regulated cells’ glucose consumption. One of those scientists, Chi Van Dang, former director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Abramson Cancer Center and now scientific director at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, showed that MYC, a family of genes regulating cell proliferation, also targets an enzyme that can turn on the Warburg effect.

Metabolism-centered cancer therapies that effectively starve tumors are no longer just a concept. Two drugs, ivosidenib and vorasidenib, have already been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for a form of leukemia and are now being tested in brain cancer patients. Rafael Pharmaceuticals’ experimental therapy, devimistat, has had impressive early results in bile duct cancer trials.

But as Apple points out, cancer is an incredibly persistent foe. It can mutate to evade chemotherapy, molecularly targeted therapies, and even newer immune-boosting therapies. The same thing may happen with metabolic therapies. What’s more, virtually all cancer treatments come with significant side effects.

That’s why the implications for preventing cancer in the first place are so important.

Population-wide studies have directly linked 13 cancers — including breast, bladder, lung, colon, liver, and gynecological cancers — to the same metabolic abnormalities that are driving the twin worldwide epidemics of obesity and diabetes. The most striking thing that the cancers, obesity and diabetes have in common is resistance to insulin, the vital hormone that enables cells to absorb blood glucose and turn it into energy. To compensate for this resistance, the pancreas pumps out more and more glucose.

The hypothesis is that patients’ high blood sugar impacts tumor growth by providing cancer cells with an abundance of the fuel they thrive on.

Apple spends almost half his book taking deep, incisive dives into research on the insulin connection. Refined sugar, which is a combination of glucose and fructose called sucrose, contributes to insulin resistance, So does fructose, or fruit sugar ― especially when it is concentrated in high-fructose corn syrup, the ubiquitous processed-food additive. Consuming fructose, a carbohydrate, also appears to make people add fat tissue more readily than actual fats, such as butter.

“Precisely how much sugar is too much may be different for each person, depending on genes and age and exercise habits and capacity to store fat safely,” he writes. “But the path from refined sugar added to our diets to insulin resistance ... to cancer is now well-understood and based on widely accepted science.”

He touches only glancingly on a fundamental problem: Even if sugar’s role as a cancer-promoter becomes an article of faith, cutting back on it is tough. And controversy, not to mention quackery, abounds in the field of nutrition. The ketogenic diet, for example, restricts carbohydrates, which are converted to glucose in the body. The diet has shown promise in weight loss studies, as well as in relieving neurological disorders such as epilepsy. But the esteemed Mayo Clinic says the diet’s high level of saturated fats, combined with limits on nutrient-rich fruits, veggies and grains, “is a concern for long-term heart health.”

In the final chapter, Apple weaves in a chilling anecdote:

“Sugar, of course, cannot be blamed for Nazism or for turning Hitler into a madman. But as his madness grew, so, too, did his taste for sweets. It wasn’t only his cherished Viennese pastries. On any given day, Hitler might consume two full pounds of chocolates. He even added sugar to his wine.”