Could mRNA vaccines conquer another deadly infection? Penn researchers say yes.

Working with animals, Penn researchers modified the mRNA vaccine to target C. difficile, an infection that kills 30,000 in the U.S. each year.

The same technology that saved millions of lives during the COVID-19 pandemic appears to hold promise against another scourge of infectious disease, according to new research from the University of Pennsylvania.

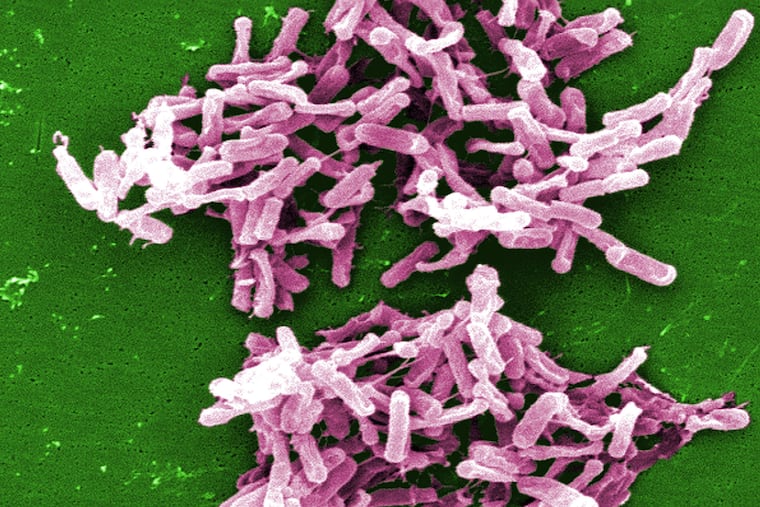

Working with mice, hamsters, and nonhuman primates, Penn researchers found that a modified version of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine — based on technology also pioneered at Penn — appeared to prevent and fight infections by Clostridioides difficile. This bacteria, also known as C. difficile or C. diff, causes half a million infections and kills roughly 30,000 people in the U.S. each year.

“C. diff is a really challenging pathogen,” said lead author Joseph Zackular, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Penn. “This vaccine is kind of a really nice proof of principle” that the mRNA technology can tackle another major public health threat, he added.

C. diff exacts damage on several fronts. It hangs out in our gut, where it can produce toxins that cause problems such as diarrhea. But it also exists as spores that live outside the body, which survive for long periods of time in soil or on surfaces, and serve as a major source of infections.

Most of the time, our bodies are able to keep C. diff at bay, but become less so as we age, and after a round of antibiotics, which can wipe out the “good” bacteria that keep C. diff in check. In a troubling trend, an increasing number of young people are getting C. diff, even without taking antibiotics.

Once someone has C. diff, it can be really hard to shake: Roughly 1 in 6 people who get C. diff will get it again within the next several weeks.

In a study published earlier this month in the journal Science, Zackular and his team modified the mRNA vaccines that targeted the COVID-19 virus to instead attack all fronts of the C. diff bacteria.

They found that mRNA vaccines that target C. diff cells and the toxins they produce generated a lasting immune response in mice and hamsters.

After giving mice 20 times the lethal dose of C. diff, all unvaccinated mice died within two days, while all vaccinated mice survived, remained alert and active, and exhibited only mild symptoms. Vaccinated mice even survived a second infection six months later. A version of the vaccine that also targeted its spores appeared to prime mice and nonhuman primates to fight off C. diff infections.

Other mRNA applications

Researchers’ next steps include continuing to test the vaccine in animal models, and eventually humans. As with any animal studies, there is no guarantee that what works in mice will also work in humans. What’s more, C. diff is not an easy pathogen to target: Sanofi discontinued its C. diff vaccine candidate in 2017, and a 2024 report showed a Pfizer C. diff vaccine failed to prevent infections in a Phase 3 clinical trial.

That said, the mRNA vaccine is an established platform, which Penn researchers are using to also target Lyme disease, norovirus, and a herpes virus, and are working on other targets such as cancer. In the future, it may be possible to develop mRNA vaccines against a number of other bacterial infections, such as salmonella, Zackular said. “There’s a lot of really, really tricky bugs that are multidrug resistant that we’re really concerned about.”

The C. diff study was funded in part by BioNTech, which made some of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines with Pfizer. In addition, Penn has optioned and licensed some intellectual property to BioNTech related to the project to develop an mRNA vaccine for C. diff, and, as such, “may receive additional financial benefits under the option and license in the future,” according to a Penn news release about the study.