Penn doctors are testing whether this new technology can diagnose cardiac arrest faster

The device, called Rescue TEE, uses a tiny camera at the end of a thin, flexible tube inserted through a patient’s throat to take ultrasound pictures of the heart during resuscitation.

Anthony Scalies was in cardiac arrest. He’d been admitted to Chester County Hospital 10 days earlier with COVID, and his health had rapidly declined.

Cardiac arrest is common among patients when they become critically ill with COVID, but it was unclear to doctors what underlying problem had caused the Collegeville resident’s heart to suddenly stop beating that day in April 2021.

Doctors face a dual challenge when patients go into cardiac arrest: Their immediate focus must be restarting the heart with CPR. But they also must quickly figure out what caused the heart to fail in the first place — and any delay can compromise the patient’s ability to recover.

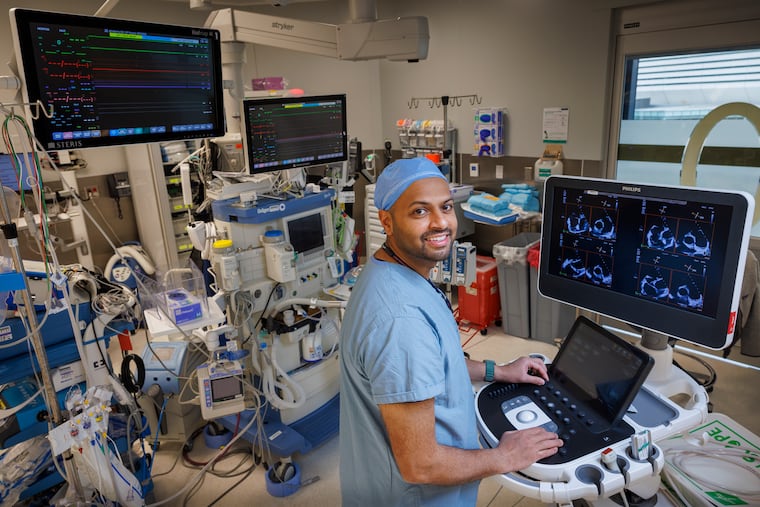

A Penn Medicine team is testing whether a new technology that gives live ultrasound images from inside a patient during CPR can help doctors get those answers faster. The device, called Rescue TEE, uses a tiny camera at the end of a thin, flexible tube inserted through a patient’s throat to take ultrasound pictures of the heart during resuscitation.

“Instead of working in the dark,” said Asad Usman, assistant professor in the department of anesthesiology and critical care at Penn Medicine, who used Rescue TEE to help determine why Scalies went into cardiac arrest.

Nationally, about 23% of patients who experience in-hospital cardiac arrest survive, said Usman.

Those who are resuscitated undergo invasive testing in the hours and days after being stabilized to figure out what’s wrong.

The Rescue Transesophageal Echocardiography for In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (ReTEECA) trial, led by Jacob Gutsche, associate chief medical officer of critical care, will compare the outcomes of patients treated with Rescue TEE during cardiac arrest to those who receive the standard CPR treatment.

» READ MORE: Penn Medicine is going all in on proton therapy, a costly treatment that is unproven for most common cancers

The trial is being conducted under the FDA’s Exception for Informed Consent for Emergency Research, a class of research that requires special approval to involve patients that are not able to consent to participating. Technology or treatments tested through this type of research must address a life-threatening medical issue for which current treatment is inadequate or unsatisfactory, according to the FDA.

Between one and five Penn Medicine patients experience cardiac arrest each week. The trial will compare treating these patients the conventional way, by administering CPR without imaging, compared to using Rescue TEE, to learn which one leads to better survival.

So far, Penn has used Rescue TEE in 100 cardiac arrest cases. Among their findings is that CPR compressions are often being done in the wrong spot, Usman said. The ultrasound images show doctors exactly where the heart is — the exact location within the chest cavity can vary slightly — allowing their chest compressions to be more precise. Everybody’s heart is in a slightly different place so when taking a picture of the heart, they learned that if a particular patient’s heart is in a slightly different spot, by simply moving their hands they can do the chest compressions precisely over the heart.

Risks of the procedure include potential injury to the esophagus from the probe or misinterpretation of image findings, which could lead to a misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis.

Usman had already been dispatched to Chester County Hospital, which is part of Penn Medicine, to help doctors develop a treatment plan for Scalies, when Scalies went into cardiac arrest. While reviving him with CPR, the team used the Rescue TEE device to determine that the right ventricle of his heart had failed, which was affecting his lungs.

Scalies had no idea he was going to be part of the trial but says it saved his life.

Two years later, he is coping with permanent lung damage and mental health issues that stemmed from his hospitalization, but he’s grateful to be alive.

The trial’s approved rules assume that patients will participate in the trial, unless they opt out in advance of being hospitalized. To opt out, you must contact the study team via phone (267-602-7025 or 610-389-6605), email (asad.usman@pennmedicine.upenn.edu or Jacob.gutsche@pennmedicine.upenn.edu), or postal mail (3400 Spruce St., Dulles Building Suite 778, Philadelphia, Pa. 19104).