Penn Medicine wants stroke, heart, and other acute patients transferred to its hospitals as quickly as possible — for their health and its finances

The University of Pennsylvania Health System's Philadelphia hospitals offer specialized, complex services, and the nonprofit's finances depend on them because they bring in more revenue.

The ambulance that rescued Betty Hayes after her March stroke at a Lansdale church took her to Grand View Hospital, a Bucks County community hospital that could only stabilize her and didn’t offer the level of care she needed for full recovery.

At 10:59 a.m., Grand View contacted Penn Medicine about a transfer to Philadelphia. Two hours later, the 71-year-old retired schoolteacher was being operated on at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, whose specialized doctors started a procedure to remove a blood clot from her brain, according to a timeline provided by Penn.

“They did the things they needed to do to get me to where I am today,” the Hatfield resident said several weeks after her stroke, already well along in her recovery.

Hayes was one of more than 5,800 patients transferred to Penn’s three Philadelphia hospitals in the nine months ended March 31, according to Penn. That’s a 16% increase from the same period the year before.

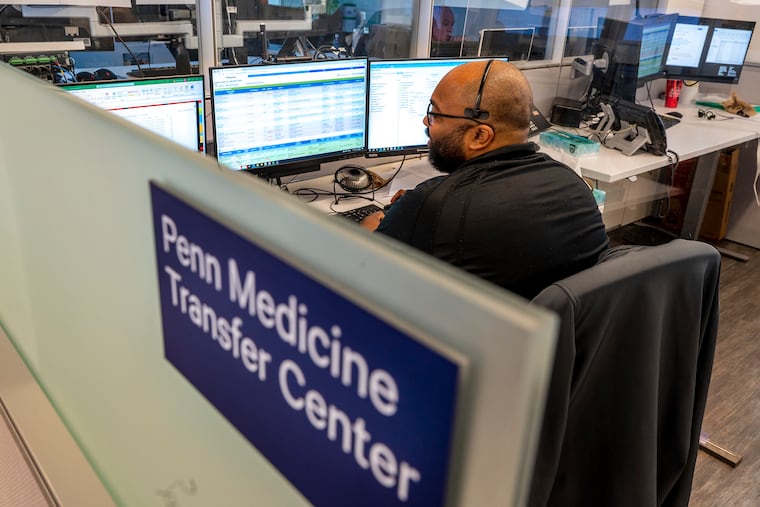

Each of those transfers starts with a call into a hub where a group of Penn managers works to connect patients quickly to Penn’s specialized medical services for strokes, liver and lung transplants, cardiac and respiratory emergencies, and complex blood cancers such as acute leukemias.

Transfer patients tend to involve three medical categories: Clotting, bleeding, and organ failure, said Bill Schweickert, a physician executive who works on patient access and patient flow at HUP.

“We generally are in the business of acute care rescue,” he said. “The faster we move, the better off we are.”

The push for efficient transfers boosts Penn’s entire network by creating a unified health system out of what would otherwise be a collection of six distinct hospitals, Penn officials said.

The flow of high-acuity patients to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, and Pennsylvania Hospital opens up access to care that isn’t available at every hospital. It’s also crucial to Penn’s business model.

That is especially the case at HUP, a national leader in treating patients who require complex and high-cost care. At the University City hospital, 13% of all patients account for more than 60% of the operating margin before overhead expenses, according to Kevin Mahoney, CEO of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

“America pays you more for advanced medicine,” Mahoney said. “Because of our advanced medicine strategy, we can fund research, we fund the work in the community. Without advanced medicine, nothing would hang together.”

The financial difference

For Penn, it makes both medical and financial sense to connect patients to specialized expertise.

Consider the financial calculus of heart surgery. When HUP cardiologists perform a valve replacement by going through a blood vessel, Medicare pays an average of $63,988 and the patient stays in the hospital for less than five days, according 2022 data from American Hospital Directory, which publishes data from Medicare cost reports.

Patients with heart ailments that don’t require surgery are less lucrative. Medicare pays HUP an average of $13,348 for hospitalized heart failure patients, even though the patient stays in the hospital nearly eight days, on average, American Hospital Directory’s 2022 data show.

Those payments, which do not include physician fees, illustrate how surgeries and other complex treatments result in greater reimbursement for hospitals.

Penn isn’t exclusively interested in the most complex and lucrative care, said Larry Kaiser, a managing director in the health care industry group at consulting firm Alvarez & Marsal.

“But Penn is the place where those kinds of cases get sent, where you have tremendous expertise in complex cardiac surgery, where you have tremendous expertise in complex neurosurgery,” said Kaiser, who was CEO of Temple University Health System from 2012 to 2020.

A measure called case-mix index is used to describe the severity of patients and the complexity of treating them. HUP’s most recent overall inpatient case mix index was 2.92, the highest in the Philadelphia region, according to Medicare.

For transfer patients, the number was even higher. It was 3.7, on average, with a range of 2.94 to 5.68 for the year ended June 30, Penn said.

Penn’s strategy is to offer “advanced medicine not just in the hospital, but across our continuum,” Mahoney said.

That includes less lucrative services and community outreach. “It’s not that we don’t do primary care. Who keeps the Mercy hospital open if you don’t believe in primary care,” Mahoney said, referring to the former Mercy Philadelphia hospital in West Philadelphia.

The proton beam therapy center Penn built in Lancaster is an example of outpatient care that isn’t available everywhere, Mahoney said.

Cancer patients were traveling 11 miles, on average, for radiation treatments at Lancaster General, he said. Adding proton beam therapy has made Lancaster a destination. “The average people travel now is 40 miles. Some of them over 100 miles.”

How transfers happen

The transfer decision starts with the attending physician.

It was a straightforward call to transfer Hayes. An ambulance crew had taken Hayes to Grand View Hospital’s emergency department after her stroke at Christ United Methodist Church in Lansdale on March 10.

Grand View has the expertise to administer drugs known as clot-busters, but Hayes still needed a surgical procedure to remove the clot.

So Grand View called the Penn transfer center. In less than two hours, Hayes arrived at HUP by helicopter. The thrombectomy to remove the clot started 10 minutes later.

An independent nonprofit, Grand View has an affiliation with Penn for specialized services in orthopedic surgery, trauma surgery, stroke care, and radiation oncology.

Penn considers stroke patients, such as Hayes, among the most critical of three groups of patients the transfer team at Penn works with. That group also includes patients who had severe heart attacks (a “stemi”) and patients with aortic dissections, a tear in the inner lining of the body’s main artery.

“The goal is to get those patients in within a two-hour time frame, whether it’s into a bed or into a procedural area,” said Amanda Whartenby, a nurse who is associate clinical director of Penn’s transfer center.

Less urgent transfers can arrive within eight to 12 hours, Whartenby said: “They are stable. The outside hospital is doing a good job managing them, but we’re able to offer something that they need that the outside hospital cannot.”

Examples of conditions requiring a transfer in that time frame are chronic liver disease, certain cancer cases, evaluations for a type of heart valve replacement, and a treatment for atrial fibrillation.

The changing marketplace

Penn’s transfer center draws from a diverse and changing network of hospitals.

Penn-owned hospitals outside the city send a little more than a quarter of the acute-care transfers arriving at its Philadelphia hospitals. Those are Princeton Medical Center, Chester County Hospital, and Lancaster General Hospital.

The biggest share of its transfers, close to 40%, come from affiliates Grand View, Virtua, Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, Shore Memorial Hospital in Somers Point, and Bayhealth hospitals in Delaware.

The remainder come from unrelated hospitals, Penn said.

The transfer center’s recent efforts to refine its procedures are part of Penn’s bid to operate as what the organization calls “one Penn Medicine.”

Lancaster General is the only one of Penn’s six hospitals still getting integrated into the transfer center’s work and is being eyed as more of a destination for transfers rather than a source, said Robin Wood, senior clinical director for HUP capacity management and the Penn Medicine transfer center.

“Lancaster General has almost every service that the downtown hospitals do,” she said.

Health system consolidation also impacts Penn’s transfer business.

Before Temple University Health System acquired Chestnut Hill Hospital, Temple University Hospital was typically getting one transfer a day from Chestnut Hill. More went to Penn and Thomas Jefferson University Hospital. After the merger, the volume of transfers to Temple increased to an average of 2.5 transfers a day, Temple CEO Mike Young said last year.

Similarly, Cooper Health’s pending acquisition of Cape Regional Health System in Cape May County may redirect the 170 or so referrals each year that Penn received from Cape Regional. In the future, they will mostly go to Cooper, Mahoney told the University of Pennsylvania board of trustees last May.

However, Penn’s proposed acquisition of Doylestown Health will protect its referrals from the Bucks County system, historically a strong source of transfers, Mahoney said in December.

In a recent interview, Mahoney acknowledged the pressure from the changing market, calling it key for Penn is to keep offering new services. “If you have a service that nobody else can put together, the patients are going to come regardless of affiliation,” he said.