Penn nurse creates app to increase HPV vaccination among teens | 5 Questions

The CDC recommends that the ideal time to receive the vaccine is age 11 to 14, for males and females. Yet only 54% of adolescents between the ages of 13 to 17 have received the full regimen.

The human papillomavirus, the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S., is related to six cancers. It is responsible for 90% of cervical and anal cancers alone.

In 2006, a ray of hope emerged with the introduction of the HPV vaccine. Research has shown that about 90% of related cancer cases could be prevented if there were widespread use of the vaccine.

The fact that many in adolescence — the optimal age group recommended to get the vaccine — remain unvaccinated has troubled medical experts who wish more people could see it as a cancer preventer and not, as some mistakenly believe, a license to have unprotected sex.

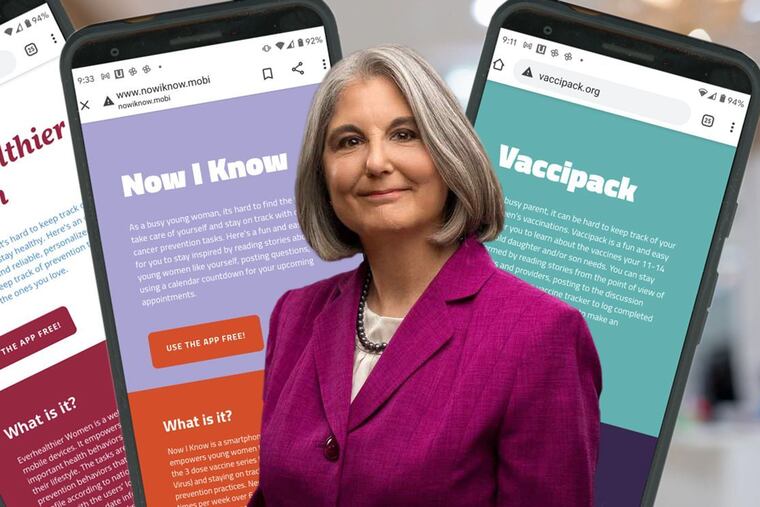

Now, a team led by Anne Teitelman, a nurse-scientist and associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, has come up with an app for that — Vaccipack.

We spoke to her recently about it.

You say the app was born of your frustration with HPV rates.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. Some HPV infections persist and can lead to cancer, including cancers of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, oropharynx, and anus. Notably, cervical cancer rates are highest among women of color in the U.S.

The HPV vaccine is very effective. So it was amazing to me that we have this highly effective biological tool that can prevent a group of cancers, and yet the uptake of this vaccine was much lower than it should be.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that the ideal time to receive the vaccine is between the ages of 11 and 14, for males and females. Yet only 54% of adolescents between the ages of 13 to 17 have received the full regimen. In comparison, that rate is much lower than the other two vaccines recommended for that age group — the meningococcal vaccine and the vaccine for tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis. Those two vaccines have uptakes in the 90th percentile.

So as a family nurse practitioner and a researcher, I wanted to find a way to increase the HPV vaccination rates.

Tell us about Vaccipack.

My research team and I created Vaccipack for parents to use with their adolescents, ages 11 to 14. We targeted parents because at that age they’re still the primary decision-makers about vaccines for their children. But we also wanted to involve the adolescents. They are developing greater knowledge of their own heath and greater interest in taking care of themselves.

Vaccipack provides information about the HPV vaccine, as well as the two other vaccines needed for the age group. An example of the education we might provide is that the HPV vaccine for this age group requires two doses, six to 12 months apart, while the other vaccines require just one dose. Another feature of the app is a vaccine tracker, which allows parents to enter their child’s vaccinations and will tell them which ones are still needed.

There are also 26 stories addressing common misconceptions about the HPV vaccines, from the perspective of parents, teens, and providers. For example, a common misconception is that if teens get the vaccine, it will promote early sexual activity. That has been studied and proved to not be the case.

Finally, there’s a discussion forum where users can post their own experiences or questions, and other users can respond.

The app is free and downloadable on Android and IOS devices.

What’s the next step for Vaccipack?

The study we just completed determined that both parents and teens thought Vaccipack was beneficial and easy to use, and the majority indicated they would be interested in using it. The next step, as far as research, would be to follow a large group of parents and teens to see if using the app actually improved completion of the HPV vaccine two-dose series.

Even if it didn’t, it would still be beneficial as a vaccine-tracker, and as perhaps an exchange of information.

You have developed two other health-related apps, with a fourth in the works.

The first, called Everhealthier Women, was in response to an app challenge from the U.S. Office of Health Information Technology. The goal was reducing cancer among women of color, who generally have higher rates of cervical cancer. This probably has more to do with access to health care for screening than anything else.

It’s a web-based app that allows users to develop a customized health action plan with reminders based on collected, curated health information related to their age and perhaps some of their risk factors, such as whether they smoke, whether they’re pregnant. Based on that, the app might provide information about exercise indicating, “You would benefit from taking a 20-minute walk every day.” So you could select that as part of your health action plan, and if you did that, the app would send you reminders.

You could also put in your action plan, for instance, if you needed a pap smear every year. The app has a tracking feature for routine health maintenance. And it has links to relevant social media posts, such as cancer support groups. It also has a nationwide locator for clinics that provide primary care on a sliding financial scale. We ended up receiving the $85,000 first prize in that challenge.

The next app was NowIKnow, aimed at promoting the HPV vaccine and safer sex among young women, ages 18 to 26. At that age, a three-dose HPV vaccine series is recommended. The features of the NowIKnow app are similar to Vaccipack, but the content is tailored to this target audience.

The most recent app we developed was a text-messaging app to help women remember to take a daily pill to prevent HIV. The target audience was women who had received a prescription for pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, from their provider. In this app, each user creates her own reminder message and selects the time of day she prefers to receive it. It was designed to address the gross underutilization of PrEP among cisgender women, who make up 20% of the HIV epidemic in the U.S. The app, Just4Us, needs further study and is not publicly available yet.

In general, why apps? How can they make a difference in the battle against cancer?

Primary care providers might only see people once a year or when they’re sick. An app is a good way to augment what providers can do between clinic visits. Also, there is so much important information we need to convey, and so little time in the clinical setting to do so. An app provides a way to offer accessible information when people want it, or when they need to use it.

With all of our apps, we solicited user input as an integral part of the development process. One of the most common suggestions for a feature was to include a way to interact not only with providers, but also with other users. So we made sure to include that feature. That’s a bonus. That’s not something you get from a PCP.

What distinguishes our apps from many others is that we build in health behavior science to help motivate people. We have some scientific understanding of how beliefs influence behavior, and if we work with those underlying beliefs, this is a proven way to motivate people and to change behavior. A lot of apps don’t go through that kind of rigorous development and testing.

The other thing that distinguishes our work is that we not only get user feedback, but we also do in-depth qualitative research to understand the context of people’s lives — the challenges they’re dealing with, the barriers, their resources, what they find meaningful, their perceptions, who their support network includes, and we factor that into our apps.

Our hope is that if we can provide people with the knowledge and skills and resources to stay healthy, in a way that they can readily use, we can reduce illness and diseases like cancer and HIV. Apps offer a lot of possibilities.