New documents show how Penn investigated a scientist found to have faked studies on newborn pigs

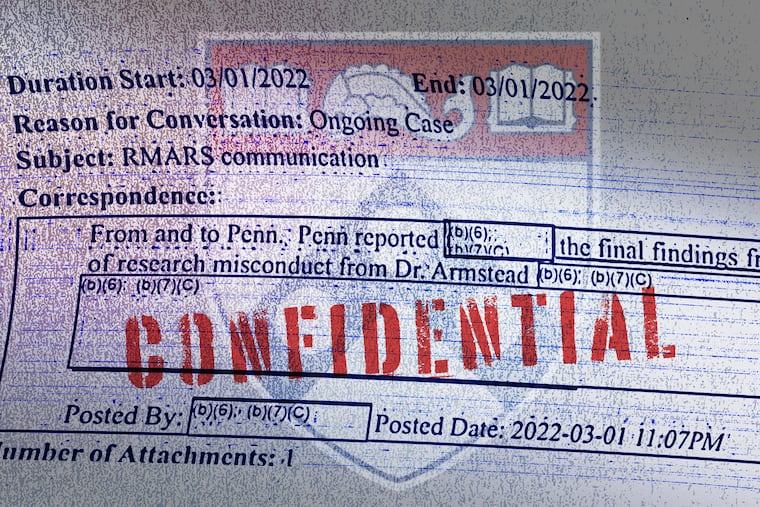

The Inquirer got a copy of Penn's findings through a Freedom of Information Act request.

The questions about the piglets with brain injuries began almost immediately.

William M. Armstead said he had successfully tested a drug on the animals in his lab at the University of Pennsylvania, obtaining results that could guide better treatment of such injuries in people.

But within weeks of his submitting the results for publication in an academic journal, the scientist and his superiors at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine were notified of a serious accusation: The manuscript included data and images that appeared to have been copied from his previous work, yet Armstead was passing them off as the results of new experiments.

That was the beginning of a four-year ordeal that ended with federal officials concluding that Armstead had deliberately falsified or fabricated 51 images, charts, and other data in a series of studies and grant applications. Armstead left his job at Penn and agreed to a seven-year ban on federally funded research.

The Inquirer has now obtained 131 pages of internal documents and emails with previously undisclosed details illustrating how the case unfolded. The records include Penn’s scathing, 23-page report on which the government’s July 2023 findings were based. Members of the school’s investigation committee wrote that Armstead was “reckless” and displayed “a blatant disregard” for accepted research practices. Citing the reused images and discrepancies in his lab records, they concluded that some of the experiments never took place.

Penn ultimately paid the government back nearly $1.7 million in grant funds that Armstead had used in his research, a university spokesperson said, responding to an Inquirer query about the report.

The report and related documents, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, offer rare insight into how universities grapple with allegations that threaten the very essence of the scientific enterprise — the quest for truth.

Research misconduct is under increased scrutiny, with more than 200 new allegations made each year to federal regulators. The advent of fraud-detection software and a growing online community of sharp-eyed sleuths have led to accusations of fakery by scientists at some of the nation’s top universities. Still, formal findings of misconduct are rare, occurring fewer than a dozen times each year.

And despite federal rules that call for prompt action, such cases often remain in limbo for years.

Penn’s lengthy investigation

That’s what happened to Armstead, 66, who was accused of wrongdoing in February 2019.

Federal regulations dictate that universities generally must complete misconduct investigations within half a year, including 60 days for a preliminary inquiry and, when warranted, 120 days for a formal investigation.

Yet the documents show that Armstead’s case dragged on for more than four years after the initial allegation, including nearly three years for the internal inquiry and investigation by Penn.

The scientist did not respond to a request for comment. His lawyer, Sidney Gold, also did not respond to several requests for comment in recent weeks.

Armstead left his job at Penn midway through the 2021-2022 school year, at about the time the investigation was concluding.

University officials declined to discuss details of the investigation or his departure, other than to say in an emailed statement that the “situation was carefully managed in accordance with all applicable university policies and federal regulatory requirements.” Federal officials granted extensions as needed to ensure a thorough investigation, the school’s statement said.

“Conducting investigations is a complex process which often requires reviewing years of publications, data, and lab notes, and interviewing former employees involved with the work in question. Penn and other institutions often find that proceedings that are both fair and complete cannot be accomplished within the target time periods, and the regulations allow for appropriate accommodations,” the school said.

The report from the school’s investigative committee also mentions one scheduling roadblock: Just weeks after the formal phase of the investigation began, the school shut down its campus in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Still, the records show that the school began its initial inquiry more than a year before that, in February 2019.

The gravity of the allegations demanded prompt resolution, said scientific integrity consultant Elisabeth Bik, a former Stanford University microbiologist who reviewed the records at The Inquirer’s request.

“Everyone had more than a full year before COVID restrictions hit, so that should not be an excuse,” she said.

Calls for faster action in such cases also have come from lawyers who represent the researchers accused of misconduct. Some investigations drag on for five years, said Christopher Ezold, who has defended scientists at several Philadelphia universities.

“They are supposed to be confidential, but confidentiality in higher education is a difficult thing to accomplish,” he said. “While these investigations are pending, regardless of what the final outcome is, they create years’ worth of mud through which research scientists or professors are dragged. Curing that reputational and career harm is almost impossible.”

The initial allegation

The case against Armstead began on Feb. 14, 2019, according to a timeline in the 23-page report from Penn’s investigation committee. That’s when a school official received an email alleging that the scientist had engaged in “possible duplicative use of data and images.”

The tipster, whose name was redacted in the copy of the report obtained by The Inquirer, had first gone to Armstead with those concerns two weeks earlier, according to the committee report. On March 4, school officials notified J. Larry Jameson, who was then the dean of the medical school (now interim university president).

The school formed a committee to conduct a preliminary inquiry, and by Aug. 30, it determined there was sufficient evidence to appoint a second committee for a formal investigation.

With Jameson’s approval, that committee went on to hold 10 meetings between Feb. 18, 2020, and July 14, 2021, during which members reviewed boxes of records, scrutinized images from tests on pig brains, and interviewed Armstead and other parties involved.

In their final report, dated Oct. 5, 2021, committee members found that Armstead:

Reused or falsified graphs and images on numerous occasions.

Conducted certain experiments with methods that differed from how they were described in published studies.

When some of his published results were called into question, could not produce original data to show where his calculations had come from.

“There was a blatant disregard for scientific record-keeping, such that published data could not be reproduced due to the vast absence of the original data,” committee members wrote.

When asked about reusing images from previous studies, Armstead explained that, in some cases, the images were from “control” animals with brain injury, not animals on which he was testing drugs. Because these control images would have looked the same from one experiment to the next, it was OK to reuse them, he said, according to the report.

Committee members wrote that this would be allowed only if Armstead had cited his earlier research as the original source, but that he did not. And in other cases, the scientist reused images from old experiments in which he was actually testing drugs, calling into question whether some of the new experiments ever happened, the committee wrote.

The committee wrote that the scientist’s failure to follow accepted research practices was “reckless” and “defies credulity.” They described his recordkeeping as “chaotic,” finding that in some cases, the number of animals he reported testing in experiments did not match what was recorded in his lab records.

Misuse of public funds

Accompanying the committee’s final report is a Jan. 12, 2022, letter of acknowledgment from Jameson, the dean. “After carefully reviewing the full report and exhibits, I accept the findings of the Formal Investigation Committee in full,” he wrote.

Two months after that, Penn paid back nearly $1.7 million to the NIH, a school spokesperson said in response to an Inquirer query. That was the total Armstead had received from the agency over five years, during four of which he was found to have submitted “falsified” progress reports to the government.

Legally, the government is entitled to recover up to three times the total of any grant monies awarded under false pretenses, said Eugenie Reich, a Boston-based lawyer who specializes in such cases. In this case, that amount would be three times the $1.4 million total Armstead received during those four years with falsified reports — nearly $4.2 million, she said.

But when universities initiate such investigations and work with the government, the cases typically are resolved for much less.

“They’re always going to get a cooperation bonus from the government if they present it,” she said.

A seven-year ban

In addition to the committee report and Jameson’s letter, the 131 pages of documents include letters and emails between Armstead, his lawyer, journal editors, and school and federal officials, in many cases heavily redacted.

They show how Armstead eventually agreed to a seven-year ban on conducting federally funded research, in a settlement announced July 3 by the Office of Research Integrity in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

At that time, four Armstead studies cited in the investigation had been retracted — meaning formally withdrawn by the journals in which they were published. A fifth, published in the journal Brain Research, is in the process of being retracted in response to a query from The Inquirer, according to a spokesperson for the publisher, Elsevier.

Armstead also withdrew the manuscript that originally prompted the call for an investigation, in which he reported treating brain injury in newborn pigs with a drug called phenylephrine.

Physicians already had been treating traumatic brain injury in humans with that drug and another one in the same class. Called vasopressors, they work by raising the blood pressure. But the evidence was unclear on which one worked best.

Had Armstead’s work not come under suspicion, he might have been onto something. Other researchers have since found that phenylephrine, the drug he said he was testing in the pigs, may indeed be the best option.