Giving birth at a young age helps protect women from breast cancer. Could a drug mimic that effect?

What if young women could take a drug that that would mimic the cancer-preventing effect of full-term pregnancy?

Having a baby before age 20 markedly cuts a woman’s lifetime chance of developing breast cancer, studies show.

What if young women could take a drug that would mimic that cancer-preventing effect of full-term pregnancy?

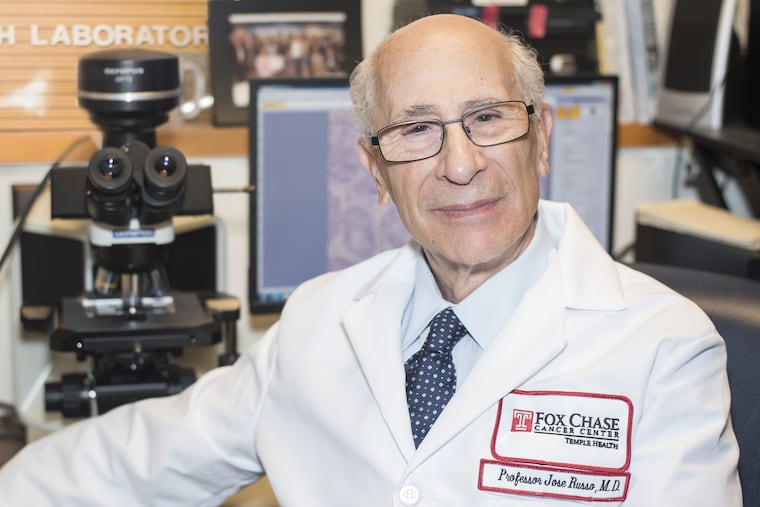

Fox Chase Cancer Center researcher Jose Russo, 77, is inspired and driven by that audacious idea.

Beginning in the 1970s, Russo and his closest collaborator — his late wife, Irma — worked to decipher the biological basis for the natural protection provided by having a baby at a young age. In March, he and an international team published the culmination of that work, defining the molecular changes, or “genomic signature,” of breasts matured by childbirth.

Russo’s team also recently completed a clinical trial in which young women with a genetic predisposition to breast cancer took a fertility drug that, in rat experiments, prevented the disease. The team is now analyzing samples of the women’s breast tissue in hopes of finding the protective genomic signature.

Russo was circumspect as he discussed the study, which enrolled 35 women in Belgium who carry BRCA1/2 gene defects.

“We are very near to having the final answer and we worry that if we talk too much, it could fall apart,” he said. “But the idea is to produce the same changes as pregnancy — without pregnancy.”

A clue from nuns

More than 300 years ago, in his famous book Diseases of Workers, Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini noted that breast cancer was unusually common among nuns. He speculated that their childlessness was a big factor.

Flash forward to the 1960s, when Harvard University epidemiologist Brian MacMahon led a study of more than 17,000 women from countries with high, intermediate, and low breast cancer rates. The results clearly showed the importance of age at first birth. Women who delivered before age 18 slashed their breast cancer risk by 60 percent compared with women with a first baby after age 35.

This reproduction-breast cancer link is complex, and it is interwoven with other factors — such as age at first menstruation and at menopause — that shape a woman’s lifetime exposure to estrogen, a hormone that fuels breast cancer.

Changing childbearing patterns are reflected in rising rates of breast cancer over the last century. In Western countries, women are increasingly having children later — or not at all. From the 1930s through the end of the 20th century, the lifetime breast cancer risk increased steadily and dramatically to one in eight women. Although incidence has leveled off, it rose by more than 40 percent between 1973 and 1998.

In the U.S., tamoxifen and raloxifene have been approved to lower breast cancer risk, but these drugs work by interfering with estrogen — not by maturing the breast tissue — and come with unpleasant, occasionally dangerous, side effects.

A legacy

Russo and his wife, who were born in Argentina, immigrated to the United States in 1971 and launched their breast cancer research lab. By studying cells and experimental animals, they provided direct evidence of what other researchers theorized: Full-term pregnancy triggers the sudden growth of milk ducts, leading to maturation of the mammary gland. When this maturation happens at a young age, it reduces the chance that genetic damage will accumulate in the cells and be copied when they divide, seeding a malignancy.

Russo’s team identified 43 genes that drive breast maturation, including genes that make the cells’ nuclear DNA go from being loosely coiled to being tightly coiled in structures called chromatin. This “chromatin remodeling” shields the DNA from genetic damage.

“What pregnancy does is make the coiling more compact,” Russo said.

Even before these molecular mechanisms became completely clear, the Russo lab published studies showing that human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) — a hormone made by the placenta to maintain a pregnancy — could be used to prevent breast cancer in rats later exposed to a cancer-causing agent.

After Irma Russo died of ovarian cancer in 2013, her husband lost hope of translating the animal findings to women. Finding funding for a clinical study, overcoming ethical concerns, and recruiting healthy women willing to undergo breast biopsies before and after treatment seemed too daunting.

Then, in 2014, Russo gave a lecture at a scientific conference in Belgium. He was approached by Herman Depypere, an obstetrician-gynecologist at Ghent University Hospital.

“He said to me, ‘I would like to try to do the trial because I have the population'” of young women at high risk of breast cancer, Russo recalled.

The 35 participants, childless women ages 18 to 30 who carry BRCA1/2 mutations, received injections of Ovitrelle — a synthetic hCG used in fertility treatment to induce ovulation — three times a week for three months. They were closely monitored for pregnancy symptoms, ovarian overstimulation, and other potential problems, but none developed, Depypere said in a presentation.

The trial is only a step toward proving that pregnancy-like protection can be artificially triggered, Russo said. Even if hCG changes the women’s genomic profiles, they would have to be followed for years to see whether that actually prevented breast cancer. And large trials would be needed to show the drug works in women without BRCA mutations.

Still, he is hopeful that his life’s work will ultimately empower women to protect their health in a new way.

“I would like this to be my legacy,” he said. “I am 77. I don’t know how long I will keep going. But the idea that we can confer protection without the necessity of childbirth is exciting. All we can do is learn from nature.”