More disease than Dracula: How the vampire myth was born

It is likely that no one disease provides a simple origin for vampire myths. But two in particular — rabies and pellagra — show solid links.

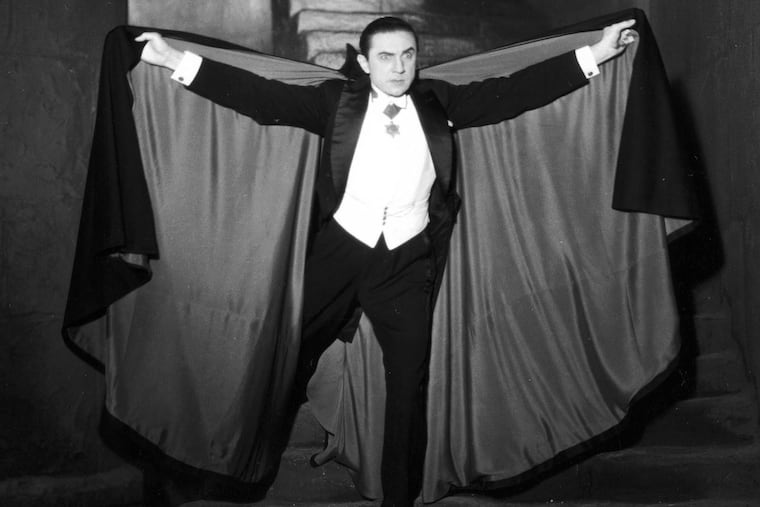

The vampire is a common image in today’s pop culture, and one that takes many forms: from Alucard, the dashing spawn of Dracula in the PlayStation game Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, to Edward, the romantic, idealistic lover in the “Twilight” series.

In many respects, the vampire of today is far removed from its roots in Eastern European folklore. As a professor of Slavic studies who has taught a course on vampires called “Dracula” for more than a decade, I’m always fascinated by the vampire’s popularity, considering its origins — as a demonic creature strongly associated with disease.

Explaining the unknown

The first known reference to vampires appeared in written form in Old Russian in A.D. 1047, soon after Orthodox Christianity moved into Eastern Europe. The term for vampire was “upir,” which has uncertain origins, but its possible literal meaning was “the thing at the feast or sacrifice,” referring to a potentially dangerous spiritual entity that people believed could appear at rituals for the dead. It was a euphemism used to avoid speaking the creature’s name — and unfortunately, historians may never learn its real name, or even when beliefs about it surfaced.

The vampire served a function similar to that of many other demonic creatures in folklore around the world: They were blamed for a variety of problems, but particularly disease, at a time when knowledge of bacteria and viruses did not exist.

Scholars have put forth several theories about various diseases’ connections to vampires. It is likely that no one disease provides a simple, “pure” origin for vampire myths, since beliefs about vampires changed over time.

But two in particular show solid links. One is rabies, whose name comes from a Latin term for “madness.” It’s one of the oldest recognized diseases on the planet, transmissible from animals to humans, and primarily spread through biting — an obvious reference to a classic vampire trait.

There are other curious connections. One central symptom of the disease is hydrophobia, a fear of water. Painful muscle contractions in the esophagus lead rabies victims to avoid eating and drinking, or even swallowing their own saliva, which eventually causes “foaming at the mouth.” In some folklore, vampires cannot cross running water without being carried or assisted in some way, as an extension of this symptom. Furthermore, rabies can lead to a fear of light, altered sleep patterns, and increased aggression, elements of how vampires are described in a variety of folktales.

The second disease is pellagra, caused by a dietary deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3) or the amino acid tryptophan. Often, pellagra is brought on by diets high in corn products and alcohol. After Europeans landed in the Americas, they transported corn back to Europe. But they ignored a key step in preparing corn: washing it, often using lime — a process called “nixtamalization” that can reduce the risk of pellagra.

Pellagra causes the classic “4 D’s”: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death. Some sufferers also experience high sensitivity to sunlight — described in some depictions of vampires — which leads to corpselike skin.

Social scare

Multiple diseases show connections to folklore about vampires, but they can’t necessarily explain how the myths actually began. Pellagra, for example, did not exist in Eastern Europe until the 18th century, centuries after vampire beliefs had originally emerged.

Both pellagra and rabies are important, however, because they were epidemic during a key period in vampire history. During the so-called Great Vampire Epidemic, from roughly 1725 to 1755, vampire myths “went viral” across the continent.

As disease spread in Eastern Europe, supernatural causes were often blamed, and vampire hysteria spread throughout the region. Many people believed that vampires were the “undead” — people who lived on in some way after death — and that the vampire could be stopped by attacking its corpse. They carried out “vampire burials,” which could involve putting a stake through the corpse, covering the body in garlic and a variety of other traditions that had been present in Slavic folklore for centuries.

Meanwhile, Austrian and German soldiers fighting the Ottomans in the region witnessed this mass desecration of graves and returned home to Western Europe with stories of the vampire.

But why did so much vampire hysteria spring up in the first place? Disease was a primary culprit, but a sort of “perfect storm” existed in Eastern Europe at the time. The era of the Great Vampire Epidemic was not just a period of disease, but one of political and religious upheaval as well.

During the 18th century, Eastern Europe faced pressure from within and without as domestic and foreign powers exercised their control over the region, with local cultures often suppressed. Serbia, for example, was struggling between the Hapsburg Monarchy in Central Europe and the Ottomans. Poland was increasingly under foreign powers, Bulgaria was under Ottoman rule, and Russia was undergoing dramatic cultural change due to the policies of Czar Peter the Great.

This is somewhat analogous to today, as the world contends with the COVID-19 pandemic amid political change and uncertainty. Perceived societal breakdown, whether real or imagined, can lead to dramatic responses in society.

Stanley Stepanic is Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Virginia. This article first appeared on TheConversation.com