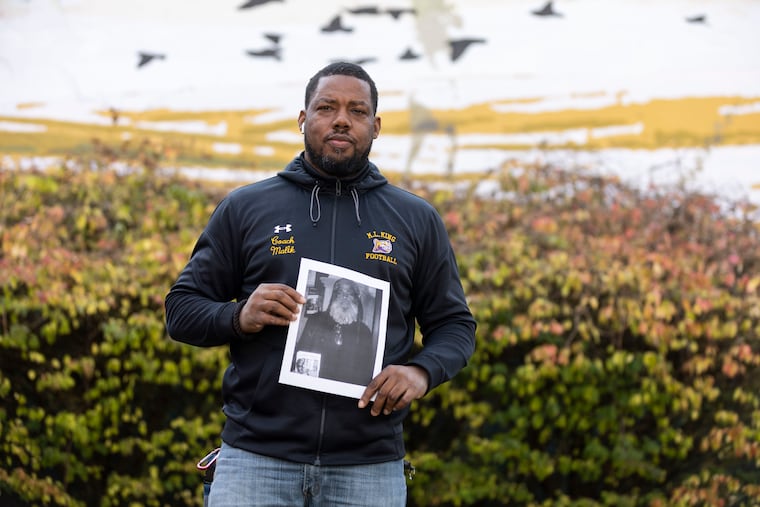

Martin Luther King football coach Malik Jones gets emotional win after death of his father

Michael Jones, a giver in the Mount Airy community, died on Nov. 9. Malik Jones was shaped by his father’s generous, empathetic spirit.

A father’s death could break hearts, but a father’s love could also change the world in ways that transcend his life span.

Malik Jones appears to be the proof.

The Martin Luther King High football coach was about 11 years old when his father’s voice bellowed, “That’s my boy,” as Jones’ older brother galloped toward the end zone during the 1990 Thanksgiving game between King and rival Germantown.

It’s the moment, Jones, who is known for positively influencing youths at his alma mater, says made him fall in love with football.

“I wanted to make my dad that proud,” the 44-year-old said in a recent telephone interview.

On Thursday, two weeks after his father, Michael Jones, died following a heart attack, Jones led King to a 45-0 Thanksgiving Day victory against Olney.

» READ MORE: Meet Bonner’s Jalil Hall, a junior receiver with a penchant for making acrobatic catches

This season, King finished 10-2, won a division championship, and went undefeated in the Public League regular season (7-0). The Cougars lost to Imhotep on Nov. 11 in the PIAA Class 5A Public League title game, two days after Jones’ father died.

“We won 10 games this season with our victory today,” Jones posted on Instagram last week, “and maybe from the heavens my dad is yelling, ‘That’s my boy!’”

For Jones, football has become more than a sport that changed his life and helped his younger brothers reach the Ivy League and the NFL.

It seems to have also become a way to honor his father’s generous, empathetic spirit.

“I watched him give up his last for others all my life,” Jones said. “[I know] that I honored my dad at every turn. I was always proud to be his son. I’ve watched him fight for people all my life.”

By all accounts, Jones is a lot like his father. Both were artists who excelled creatively.

Michael Jones, 73, was also often on the move. That’s one reason Jones didn’t miss a game after his father’s death.

“He wouldn’t have stopped,” Jones said.

Neither cancer, chemotherapy, nor a stroke slowed his father down for long.

In fact, when his dad had a stroke during the pandemic, Jones and his siblings tried, often in vain, to get him to be still.

Little, it seems, stopped Michael Jones once he had a goal. His apple didn’t fall far.

“The biggest thing about Malik is that he’s determined,” said Carole Campbell, Jones’ stepmother. “His determination is what drives him and it helps him drive others, and Michael was the same way. He was driven to help others. Maybe just not in a conventional way.”

Jones said his father was “a staple” in the Mount Airy community, where he was known for helping others.

Jones has been walking a similar path since he was a senior in high school.

Back then, Jones knew of a talented middle school player from the neighborhood who couldn’t afford equipment. So, Jones bought it, taught him the game, and became a mentor.

Jones, who grew up with eight brothers, had wanted to play for the Mount Airy Bantams after watching his older brother, Michael, now 48, score a touchdown in that ‘90 Thanksgiving game at now-closed Germantown.

But, Jones said, his family couldn’t afford the equipment. So, Jones waited until he was old enough to work.

At 14, he worked “under the table,” washing dishes at a local restaurant. Eventually, he bought hand-me-down pads and a helmet from someone in the neighborhood.

“I tell my players all the time that I had a helmet with no ear pads,” Jones said. “I had to borrow every piece of equipment. My jersey was an old T-shirt. That’s how ambitious I was about playing the sport.”

So, Jones, who was around 18 at the time, knew how Shaheed Rucker felt when his family couldn’t afford his equipment.

“He was very similar to his father,” said Rucker in a phone interview. “Malik was also that guy in our neighborhood to nurture talents, and it wasn’t just sports.”

Rucker, now 37, later stopped playing football in high school. He eventually went to Bethune-Cookman University and earned a degree in psychology.

After graduation, he founded a marketing and branding agency around creative skills he says he was first introduced to through Jones.

“Malik was at the forefront of my whole outlook on positive and negative, who to gravitate toward and who not to gravitate toward,” said Rucker, who now lives in Atlanta.

Even when Jones went to college at Bloomsburg, where he also played football, the two kept in touch.

“I’m an artist today and a lot of it has to do with watching Malik as a graphic artist,” Rucker said.

It seems, however, that Jones and his father diverged in at least one way.

Jones explained that his father, who was affiliated with MOVE and was staunchly against police brutality, was less concerned with formal education and perhaps more interested in learning through experience.

Eventually, though, Jones said his father came to appreciate the path he chose and how it may have influenced others.

“He came around and changed his perspective,” said Jones, who has three children. “He loved me. He was proud of me, and he expressed it.”

Jones’ brothers Rashad and Ibraheim Campbell, who both played football at Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, eventually followed that collegiate path, playing at Cornell and Northwestern, respectively.

» READ MORE: Why Neumann Goretti defensive back C’Andre Hooper is ‘one of the best-kept secrets in the city’

Ibraheim was drafted by the Cleveland Browns in 2015 and played seven seasons in the NFL.

Now in his fifth season as the head coach at King, Jones continues to help players reach college, including Villanova defensive back Tyrell Mims.

Perhaps for Jones it will become a way to maintain a connection with his father.

“I watched him sacrifice his own safety, freedom, and happiness to make sure everybody else was OK,” Jones said. “And to know a lot of what I’m doing is essentially sacrificing to be here for these young people through coaching this game, I’m carrying on his legacy.”