This week in Philly history, a man and a computer face off in the final match of an intensely followed chess tournament

Garry Kasparov faced off against Deep Blue at the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

Man, ultimately, won the chess match against machine.

But in their 1996 tournament, the IBM supercomputer dubbed Deep Blue was shockingly effective. It routinely matched wits with Russian grand master Garry Kasparov. Their six-game competition, held in Philadelphia in the waning years of the 20th century and on the cusp of Y2K hysteria, hinted at the technological revolution awaiting the world in the new millennium.

“For the first time in the history of mankind,” Kasparov said after the February 1996 contest, “I saw something similar to an artificial intellect.”

Kasparov, then 32, was the highest-rated player in the history of the game when he faced off against Deep Blue at the Convention Center. It was the first match between a computer program and a grand master to be held under strict tournament conditions. The matchup was the centerpiece of a 50th anniversary celebration of the first general-purpose electronic computer, which was developed at the University of Pennsylvania.

Kasparov called it a test of humanity’s dominance over machines.

But there were humans behind Deep Blue. About 200 IBM computer scientists and at least one chess grand champion spent six years developing the supercomputer with a singular goal: to beat a world-class player.

In the tournament, the Russian champion sat across from an IBM scientist with a desktop computer. The scientist sent Kasparov’s moves to Deep Blue, which operated out of a northern New York laboratory. The supercomputer’s 32 processors whirled through high-speed computations, evaluated millions of chess positions in seconds, and sent back a countermove.

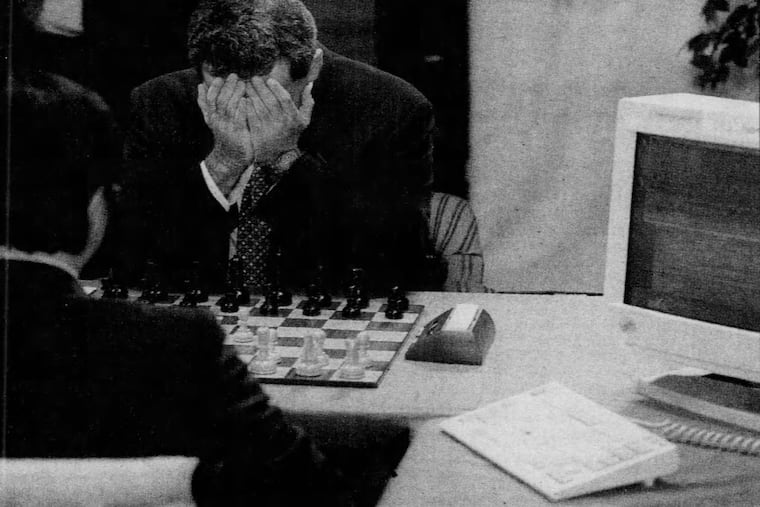

Five million people worldwide logged on to the internet to follow the match in real time as Kasparov hunched over the board and held his furrowed brow in his hands.

In game one, Kasparov’s knack for using bold and aggressive moves and intimidating body language was lost on Deep Blue.

Human players can be goaded into final defeat. They can be made to believe that they cannot win.

But the computer couldn’t be bullied.

Kasparov was under pressure early, and resigned in the 37th move, as a few hundred rowdy spectators who paid $20 to watch the match on large screens in a convention meeting hall were quieted in disbelief.

It was a historic win for the computer, and for the machine’s human programmers.

Kasparov won the second match by being uncharacteristically cautious. The third and fourth matches were beset with technical difficulties, and ended in draws.

Kasparov dominated the fifth match, beating the computer by walking a fine line between “brutish aggression and poetic form,” an Inquirer reporter wrote.

And on Feb. 17, 1996, Kasparov beat “Deep Blue” in the sixth and final round of their series, winning 4 games to 2, and taking home the grand prize of $400,000.

Though powerful, the computer couldn’t disguise its strategies and lacked an effective endgame.

Commentators said the win could be traced to a signature human ability: learning from our mistakes.

But only a year later, in May 1997, Kasparov lost a rematch with Deep Blue.

Checkmate.