Forget football. Cross-country is a second autumn sport that deserves praise | Bill Lyon

Cross-country runners get shin splints and blisters on their feet and runny noses and watery eyes. They also get a special kind of self-satisfaction that few of us are ever privileged to experience.

This column originally appeared in The Inquirer on Oct. 24, 1976.

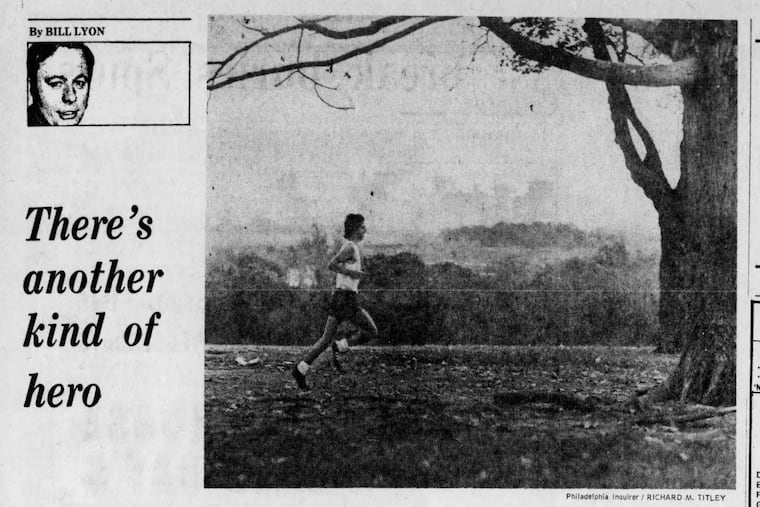

A cold wind blew the golden leaves across the hard ground. They made a rasping sound, like a death rattle.

It was a sound that matched his breathing. Harsh and grating and painful.

The sweat was frozen in crystal crusts at the end of his hair that flopped each time he took another stride and his feet fell heavily, jarringly, on the ground.

He wore sneakers that were tattered and shredded from the shrapnel of a thousand small pebbles over which he had run. His sweatpants were gray. It was a color that matched his complexion.

His arms drooped with exhaustion, like the flowers bending to give way to winter, and his was a lost, hopeless cause. For the winner was already across the finish line, far ahead, out of sight. And the other runners had long ago left him behind.

His legs screamed at him to stop. His lungs pleaded for rest. Even his socks seemed to fly at half-mast around his ankles, soiled flags of surrender.

» READ MORE: Thanks to 3D-assisted surgery, this dog survived to comfort his grieving family

In the autumn of our dreams, we are all quarterbacks. We are cunning and graceful and when we step into the huddle everyone bends forward eagerly and the crowd rises expectantly because it knows we will deliver the bomb just as the clock blinks down to zero.

Ah, but that is in the autumn of our dreams, not the winter of our reality.

You want to know about reality? Then go watch the other autumn sport. It is called cross-country. Watch it and you will know what they mean when they speak of the loneliness of the long distance runner.

Cross-country runners don’t get scholarships. Or no-cut contracts. Or offers to endorse deodorant or panty hose or coffee or cars.

Cross-country runners get shin splints and blisters on their feet and runny noses and watery eyes. One thing more. They get a special kind of self-satisfaction that few of us are ever privileged to experience.

Oh, it is not from winning. It is merely from finishing, from ever going out there in the first place and running through puddles and briar patches and up hills and down hills and telling lies to your legs, and running on even when the others pass you, one-by-one, and geez, don’t they ever get tired, don’t they have a chest that’s on fire, don’t they ever get the dry heaves, and who cares anyway because there’s no crowd, no cheerleaders, just hard ground and ugly ol’ trees with no leaves and some guy driving by in a car, honking his horn and grinning like an idiot, and oh God why don’t I just slow down and walk for a little ways? That, friends, is reality.

Oh, us silly damn sports writers, we get all caught up in downs-and-outs and slam-dunks and power-play goals and a frostbitten World Series, and sometimes we get the notion that what comes out of the mouth of some semiliterate who is a millionaire only because his glands went berserk at an early age ranks right up there in importance with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

So we tend to dismiss things like cross-country as “minor” sports, and besides, who the hell knows how to read a stopwatch past the 4-minute mark anyway?

So in our jock fantasies, the hero is the guy who scores the winning touchdown. But that is not reality. Reality is the kid you’ll see when you’re driving through a park or past a golf course, the kid with the stocking cap and the sweat-stained sneakers, loping along way behind the field, his eyes rolling wildly, this hypnotic trance of pain and puzzlement contorting his face.

Maybe he will not be able to put into words exactly why he runs. Maybe he will mention something about “gutting it out” or pushing through the pain barrier or running on because he has this curiosity that drives him to discover just how much he is capable of… or not capable of. That can be the harshest kind of reality and anyone who is willing to confront it, then he is, in the truest, purest sense, an athlete.

UPdate: Former Philadelphia Inquirer sports columnist Bill Lyon wrote for the broadsheet for 33 years before retiring in 2005. After Lyon was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2016, he chronicled his struggles in a series for the newspaper. He died in 2019 at 81.