It’s official: Science has proven that black doesn’t crack | Elizabeth Wellington

Thanks to a Rutgers New Jersey Medical School study, grandma’s quip is truer than ever. And the reasons are far deeper than the melanin that helps darker skin from the ultra violet rays that lead to wrinkles. It goes right on down to the bone.

Whether we are discussing Angela Bassett’s flawless face after the Oscars, or trying to figure out how it’s possible the pretty sister at work still looks 25 when we know she’s pushing 40, the African American community turns to this trusty, old school adage: Black don’t crack.

Now thanks to a Rutgers New Jersey Medical School study, grandma’s quip is truer than ever. And the reasons are far deeper than the melanin that shelters darker skin from the ultraviolet rays that lead to wrinkles. It goes right on down to the bone.

Black people are not only born with denser bones in our faces, those bones also don’t break down as quickly — especially the bone between the eyes and the cheekbones — as our Caucasian counterparts. The result: Black faces maintain structural support for a longer period of time so we have younger-looking skin for longer.

“This is why black people look like themselves longer,” said Boris Paskhover, a facial plastic surgeon at Rutgers who spearheaded the study as a way to better understand the aging process as it relates to the bones in the face. As we get older, Paskhover said, black faces, like all faces, change, but the bone structure in black people doesn’t change at the same rate as in Caucasian faces, he said. “If we can understand what causes the face to look older, then we can perhaps one day understand how to prevent the aging process without surgery.”

The study, “Long-term Patterns of Age-Related Facial Bone Loss in Black Individuals,” published in JAMA Facial Plastics in April, looked at the faces of 20 people — six men and 14 women — between the ages of 40 and 55. It’s a small study, but authors believe it’s the first to assess changes in bone structure among black subjects, though it’s been done among whites, so the authors have work to compare it to. The study includes black folks from all over the world, not just African Americans.

Black don’t crack is a term I’ve actually cautioned against using. Sure, it’s nice that black women look younger for longer. But the phrase can be detrimental. People who look as good as we do for as long as we do disproportionately suffer from high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity and depression.

But pardon me while I take the time to giggle.

Part of what led Paskhover to the study is that he knew that black people have denser bones. Black men, he said, are the gold standard of bone health. And he was also familiar with studies that proved black women had lower rates of osteoporosis because, generally speaking, black women’s bones don’t wear down as fast.

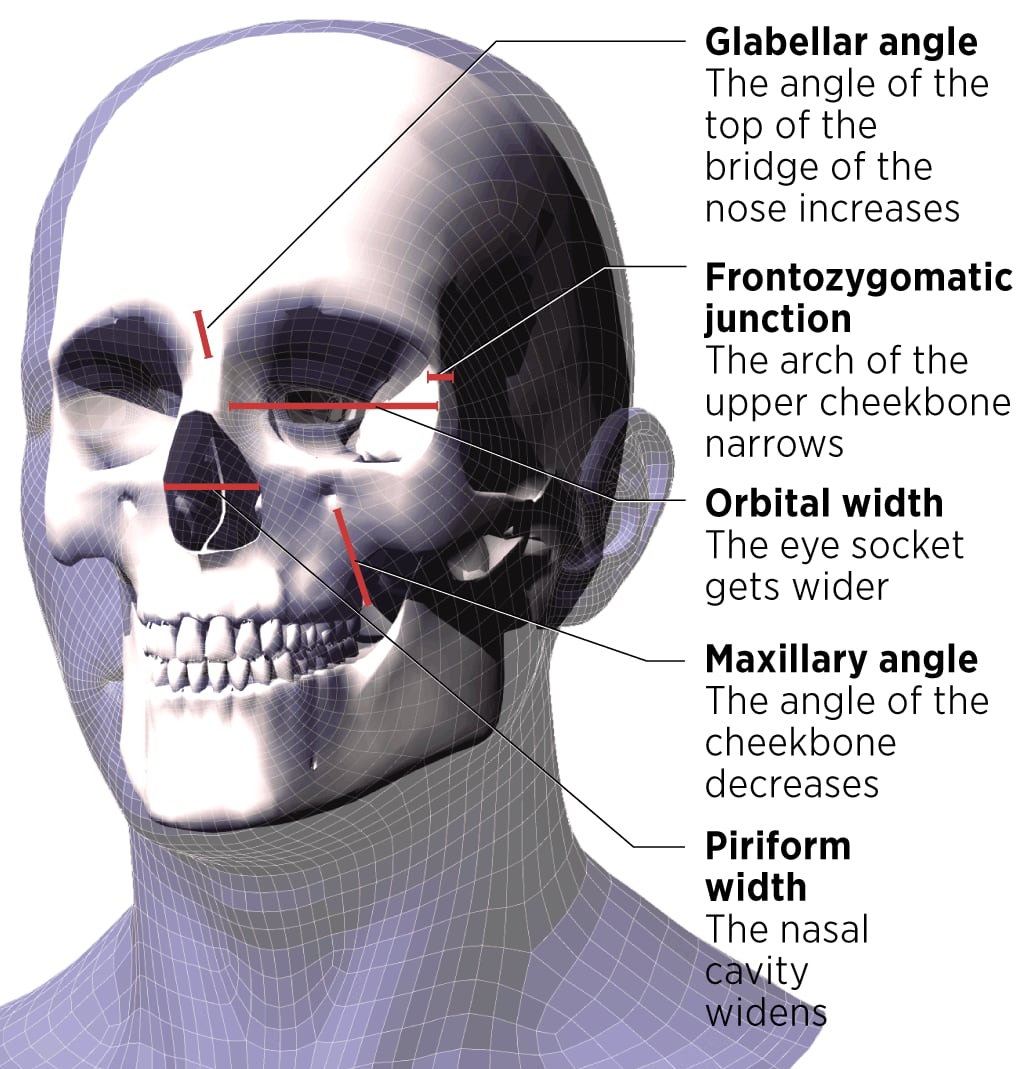

Measuring Aging in the Skull

The shape of the skull changes with age due to a process known as resorption that results in loss of bone mass. Areas of the skull indicated here are commonly used by researchers to measure changes as the body ages. The most noticeable changes are widening of the eye and nasal openings, and changes in the angle of the cheekbones and the upper bridge of the nose.

Glabellar angle

The angle of the top of the bridge of the nose increases

Frontozygomatic junction

The arch of the upper cheekbone narrows

Orbital width

The eye socket gets wider

Piriform width

The nasal cavity widens

Maxillary angle

The angle of the cheekbone decreases

Glabellar angle

The angle of the top of the bridge of the nose increases

Frontozygomatic junction

The arch of the upper cheekbone narrows

Orbital width

The eye socket gets wider

Maxillary angle

The angle of the cheekbone decreases

Piriform width

The nasal cavity widens

[Can’t see the graphic above? Click here to view the complete article.]

Yet this perceived “strength” was part of why black people were considered good chattle. And when it comes to beauty, it’s why a whole host of black women — including former first lady Michelle Obama — have been historically harangued by racists who point to our strong facial features as reasons why we “aren’t as desirable” as white women. But it’s these same impenetrable and resilient bones that give black women the beauty one-up, a prolonged fountain of youth. There isn’t enough Botox in the world that can compete with Mother Nature.

“Every day I meet people on the street who stop me and tell me how good I look,” said Trudy Haynes, 92, who was the nation’s first African American meteorologist and in 1965 became the first black woman to work as an on-air reporter in Philadelphia at CBS. “‘What do you do?,' they ask me. ‘How do you keep it up?’ Nothing really, I just use those wipes to take the makeup off. That’s pretty much it.”

Paskhover is a 33-year-old white man who was born in a small town in Eastern Europe, but who grew up in my home borough of Queens, where he was immersed in a diverse culture. Paskhover’s approach to understanding the aging face is refreshingly modern. In fact, it was Paskhover who was behind the Rutgers study proving our noses actually look 30 percent bigger in selfies. It’s part of the reason why, he concluded, younger patients sought surgery for smaller noses.

Before Paskhover arrived at Rutgers he was a neck and surgery resident at Yale. He launched the initial study on the boney structure of the aging face back in 2014 that studied the CAT scans over time of patients at Yale. But all of his patients were white. When he moved to Rutgers in 2017 and realized the hospital actually served a large minority population, he decided to study the CAT scans of black people.

“I wanted to turn this into an opportunity to figure out what’s happening in the black community," Paskhover said.

He took the old CAT scans of 20 black patients without facial trauma or cancer and measured the bone density of each one. Then he measured the bone density of those same patients six to 10 years later.

Paskhover and his team looked at five key places where bone breakdown is common: the space on the forehead between the eyes, the cheekbones, the bones at the nasal opening, the orbital width of the eye and frontozygomatic junction or FZ junction, which is an unmoving point over the right eye at about 3 p.m in a mirror image. There was change in all points but overall, “the bony features were relatively stable compared with the patterns of change observed previously in the white population,” according the study.

Understanding how the boney processes underlying facial aging differs among the races will become key in counseling patients and creating individualized treatment plans. After all, cosmetic surgery is going up among all people, including African Americans who, according to the study, as of 2017 were outpacing whites in cosmetic procedures.

“It’s really about understanding the underlying causes that will prevent aging in all people," Paskhover said. “Right now, we tend to target the skin for underlying age problems, but maybe we should be targeting the bone.”

So now, thanks to Paskhover, not only can we proudly say to each other that black don’t crack, but we can now add another: Beauty is more than skin-deep.