The son of a combat veteran created a comic book about his father’s wartime service

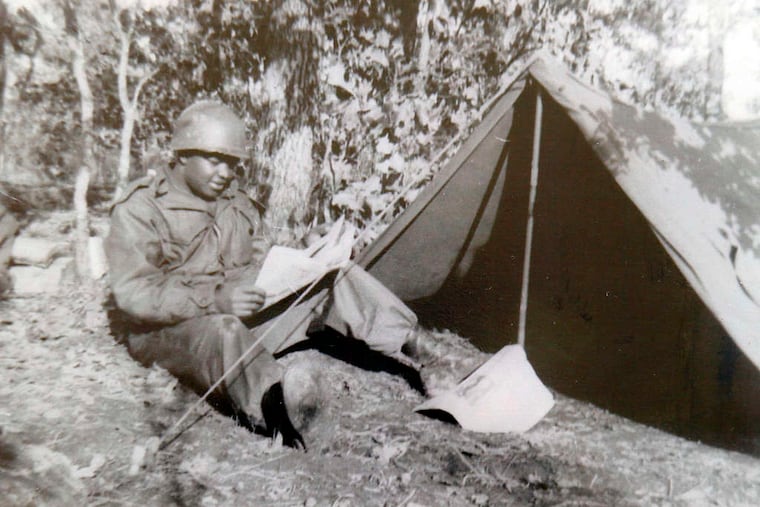

Clarence Davis's memoir about being a Black soldier during the Korean conflict has been made into a comic book and animated video by his son, the filmmaker and music producer Gary Davis.

When Gary Davis and his five younger siblings were growing up in Camden, their father, Clarence, meticulously documented family life in photographs and home movies, using professional equipment he had learned about while in the service.

Clarence Davis spoke often about being on the front lines as a Black soldier in the newly integrated U.S. Army during the Korean War. He even wrote a memoir about his combat experiences. In 2019, Gary Davis began to transform his dad’s written and oral stories of wartime into an action-packed, handsomely illustrated comic book titled Escape from Kumwha.

It will soon be available in print, and an animated version is also in the works.

“My dad inspired my imagination,” said Gary Davis, 67. “By the time I was 10, I was shooting my own movies of my brothers and neighborhood kids, and writing stories.”

A West Palm Beach, Fla., resident, the younger Davis has been the creative force behind dozens of independent film, video, TV, music, and comic book projects since the late 1970s. Got To Get Your Love, a disco single he wrote and arranged, remains a favorite among British DJs.

“My dad introduced me to creative tools,” said Davis, who crafted an episodic narrative and commissioned the Argentinian graphic artist Hugo Martinez to illustrate it in a traditional black-and-white comic book format.

» READ MORE: Girls High grad is promoted to colonel in U.S. Army

“When I read some parts of the book, I teared up, and at others, I was laughing. This stuff was real,” said Clarence Davis, who turned 91 in January. The retired Camden public school industrial arts teacher, longtime Cherry Hill resident, and grandfather of eight is living with family in Voorhees following the death of Eleanor, his wife of 69 years, last March.

The seventh in a series of comic books Gary Davis has created (most of which are set in the year 2052 and feature martial arts and futuristic villainy), the 32-page Kumwha book mixes lighthearted and dramatic vignettes. They’re narrated by Gary Davis and expertly rendered by Martinez, who’s 37 and lives in Buenos Aires.

“What particularly appealed to me about Gary’s project is that … it’s a true story [and] it’s the story of his own father. That makes the project more challenging,” Martinez, whose work can be found on Instagram, said in an email. “I really appreciate that he trusted me to tell such a personal story.”

“Pop” Davis runs into Eugene Bagwell, a friend from Camden who eventually became a city police officer, while at the Korean front; helps a buddy whose knee has been shattered by enemy fire; and watches in horror as the first Black lieutenant he had ever seen in Korea is thrown to the ground after a bomb shatters his truck.

”Was he dead?” Davis wonders to himself in the comic, before being stunned to see the lieutenant get back up on his feet.

» READ MORE: Best comic book stores in the Philly area

“My father told us these Korea stories so many times I felt like I’d been there,” said Dwayne Davis, 60, an ice cream vendor who lives in Cherry Hill. “We are all proud of him for his service to this country. The book is wonderful and I know it means a lot to him.”

Said Davis’ youngest child and only daughter, Sharon Davis, an educational consultant in Ocean County: “I had heard the stories, but what the comic book brought home for me was how horrific it must have been for him at just 21 years old. War is horrible.”

Clarence Davis was drafted in 1951 and served 15 months in Korea with the 625th Field Artillery Battalion, 40th Infantry Division. He saw action during the brutal, protracted Punch Bowl and Heartbreak Ridge battles.

Although President Harry S. Truman had issued an executive order to desegregate the armed forces three years earlier, the integration process “wasn’t complete,” said Davis. For a time, he was the only Black soldier in his bunker.

But having grown up poor in Camden’s Centerville neighborhood, which had long been home to Blacks and whites, Davis easily made friends across the color line. “I liked country music, and introduced it to a white guy from New York who told me about Billie Holiday,” he said.

Black soldiers often got the worst assignments. But Davis’ truck-driving skills (he was master of the double-clutch) earned him respect. He also earned a sergeant’s stripes before completing his two-year hitch in 1953.

Back home, Davis and his wife, a nurse, started their family. He worked as an electronics technician at RCA in Camden, moved his family from South to East Camden, and began collecting cars. He also changed careers, becoming a shop teacher in the Camden public schools in 1972. He retired from Woodrow Wilson High School in 1996.

After retirement, Davis became active in veterans organizations, spoke regularly to school groups, and participated at the Cherry Hill Public Library’s oral history project about local veterans. He said he didn’t want the service of Black soldiers in Korea, or the conflict itself, to be forgotten.

Gary Davis doesn’t want that to happen either. And as the married father of a grown daughter, he understands the importance of not only preserving but curating, and sharing, a family legacy.

“For me, this project is a huge deal,” he said. “It means the whole world to me. And it hasn’t even fully come to fruition yet.”

Said his father: “I’m tickled to death by what Gary has done. Words are not [thanks] enough.”