From Gimbels to Gritty: Looking back on a century of Thanksgiving Day parades in Philadelphia

The parade is thought to be the oldest Thanksgiving Day parade in the country, established four years before its New York/Macy’s counterpart.

In November 1920, a couple of dozen Ford Model Ts rolled through Philadelphia, one containing Santa Claus, who made his way to Gimbels, then went eight stories up to its toy department.

It was the city’s inaugural Thanksgiving Day parade, and it drew barely as many onlookers as marchers (55). The parade is thought to be the oldest Thanksgiving Day parade in the country, established four years before its New York/Macy’s counterpart.

In the intervening century, the parade has grown rather more popular — one million people turn up on a good autumn day.

As the centennial of what is now known as the 6ABC Dunkin’ Thanksgiving Day Parade approaches (yes, the math adds up, even though it’s 2019), we thought we’d take a look through the archives to see how the celebration has evolved over the years.

In the early days, most information about the parade appears in advertisements — it took time for Gimbels president Ellis Gimbel to build momentum for the event, which he always viewed as a way to draw attention to the Christmas shopping season.

Hence the gimmick, part of the parade since its inception, of having Santa lifted by ladder to the upper floors of the department store (at Ninth and Market), where he climbed through the window to the store’s Toyland section. Gimbel designed the parade to please children, and always invited orphans to share the stage with him — as many as 4,000 in later years.

There are intriguing references to a Roaring Twenties mishap: During one of those early years, Santa apparently lost his footing on the way up and had a close call. By the 1930s, he was followed up the ladder by a radio personality named Uncle Wip (on loan from WIP) to provide backup.

By then the Depression had taken hold, and also Prohibition, though reporters who covered the parade appeared, somehow, to have gotten a snootful. Here’s an Inquirer scribe letting readers know that Santa always found children to be nice rather than naughty: “The plump Gentleman in Cerise, much to the exasperated opinion of the Philadelphia Police, found everybody good and toy deserving.”

The mood at the parade, he wrote, ran counter to the era’s brother-can-you-spare-a-dime paradigm: “Every inch of it seemed to defy the hard time ghouls of gloom.”

In 1934, Kate Smith came to perform, and the parade was littered with “many Mae West impersonators” mixed in among the throng of 2,000 marchers, 94 floats, and 40 marching bands.

A few years later, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson was a guest of honor. At age 61, he was to ride in a car from the Philadelphia Museum of Art to Gimbels, but at the urging of the crowd, he jumped out of the vehicle and tap-danced the entire way.

By 1939 the parade had become so popular — half a million attendees — that lost children had become a recurring problem. “The parade gave police their annual headache — lost children. Eleven youngsters between the ages of 3 to 11 were turned over to police between 9 a.m. and noon.” (All were retrieved by 9 that evening.)

World War II rationing had its effect. In the early 1940s, a civilian gasoline ban meant that all floats were horse-drawn, and reports say “nearly all of the marchers were women.” The parade in wartime grew patriotic. The Statue of Liberty and Winged Victory became a fixture, and iconic Borden Dairy mascot Elsie the Cow anchored a float whose riders made a pitch for war bonds.

In those early decades, the parade’s floats and marchers were modeled heavily on storybook characters. Mickey Mouse and Bambi might show up, but for the most part the parade featured folktale figures like Peter the Pumpkin Eater. Pecos Bill, Paul Bunyan. Jack the Giant Killer, Ali Baba, and Humpty Dumpty. Something called “The Pinhead Man from Pinsylvania” once appeared.

Postwar, the parade upped the ante on spectacle, and by 1950 the main attraction was a “green-eyed yellow dragon, a monster that measured 60 feet from the tip of his smoking snout to the last of his 13 lashing tails. He was an altogether terrifying sort of dragon.”

Terror, in the Eisenhower era, had a more innocent connotation. In 1957, police arrested a teen “with a loaded gun in his pocket.” The officer had been alerted by “complaints of drum majorettes that somebody was firing pellets at them.” Police spotted the scoundrel, who “tried to conceal the gun when they approached.”

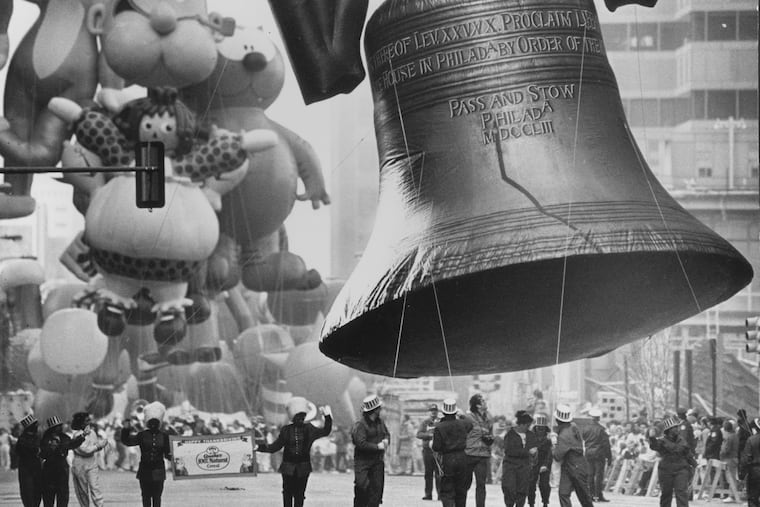

Pellets might have done serious damage to the gigantic tethered balloons that have long been a parade highlight, usually drawing from TV and movies — Popeye and Olive Oyl, Felix the Cat, Lamb Chop, Underdog, Mighty Mouse, Fred Flintstone.

Verily, there is no sure thing on Thanksgiving Day. The parade was canceled once in 1971 due to bad weather (though marchers took a few turns around the Art Museum for the benefit of television crews). There have been periodic attempts to eliminate balloons as a feature, because they are difficult to wrangle. Even motorized floats have been forced to withdraw. During the 1970s, the Alice Cooper float “suffered damage and was removed.”

The parade outlasted Ellis Gimbel (he died in 1950), and Gimbels itself folded in 1986. Still, though the routes and rituals and sponsors have changed, the parade has remained popular with Philadelphians. Perhaps more popular with fans than with invited celebrities — no-shows pop up here and there. Ventriloquist Jimmy Nelson demurred in the 1950s (plane fogged in, he said), and in the 1970s, Jeffersons star and South Philadelphia native Sherman Hemsley called in sick.

Some years, we seemed to be hard up for marquee names — people once stood in the rain to watch Richard Sanders, who played Les Nessman in WKRP in Cincinnati.

On the other hand, the parade snagged Liberace, Joey Bishop, David Brenner, the Harlem Globetrotters, Mario Andretti, Joe Frazier. Nell Carter and Kool and the Gang joined the party. Bernie Parent, Hank Aaron in 1976, Mike Schmidt in 1980. This year, for the 100th edition, Il Divo, Macy Gray, and Kathy Sledge are scheduled to attend.

And while we don’t have a green-eyed yellow dragon spanning 60 feet with 13 writhing tails, we have this:

A historical marker commemorating 100 years of the Thanksgiving Day parade, mounted atop a 10-foot pole, was installed Nov. 26 at the western edge of the Oval, at the crosswalk nearest to Ericsson Fountain, 2451 Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

The parade itself begins at 8:15 a.m. Thursday from 20th Street and JFK Blvd. It will be televised on 6ABC: 8:30 a.m. until noon. From its starting point it proceeds east on JFK to 16th Street, turns left onto 16th Street to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, then up the south side lanes of the Parkway to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The parade is free, just the way Ellis Gimbel wanted it.