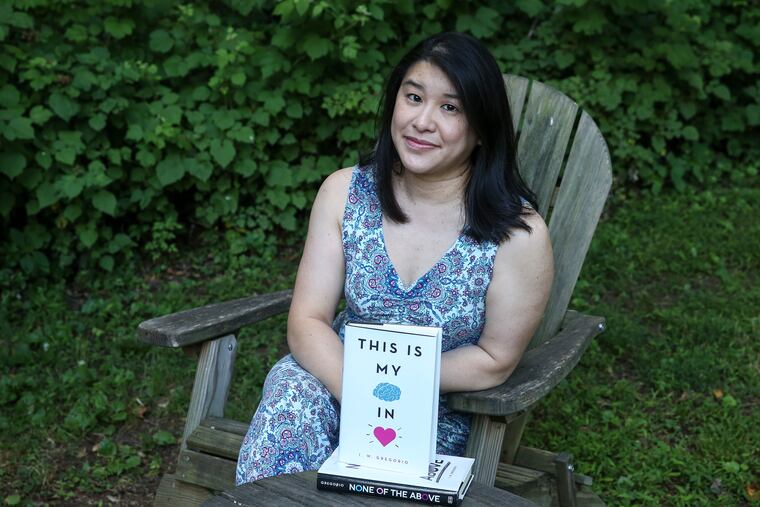

This West Chester mom is an Ivy League-trained urologist by day and a novelist by night

Ilene Wong writes the type of novels she wishes she could have read as a teen.

Jocelyn Wu, the main character in the new Young Adult novel “This Is My Brain in Love,” lets readers know up front that her story is going to be a mostly happy one about mental illness.

“I say this to you because I want you to be reassured,” she says. “I want you to know so when the story ends with me staring at a pill bottle, wrestling with what to do with it, you’re prepared.”

That’s good, because readers can really get to like Jocelyn — she’s smart, she’s funny, and she’s dealing with a lot of tough stuff. In addition to the mental health issues that pill bottle is all about, Jocelyn is also falling in love, her family is having money problems, and — because there aren’t many other Chinese American kids in her upstate New York community — most of her peers don’t look like her, so she doesn’t always feel like she fits in.

The adolescence of Ilene Wong, author of “This Is My Brain in Love” (written under the pen name I.W. Gregorio), was in some ways not unlike character Jocelyn’s. Wong grew up in Utica, N.Y., one of only a few Chinese American kids in her community, and dreamed of being a writer. Her new novel, Wong said, is the kind of book she wishes she had when she was younger — “a book I would have read and been able to have said, ‘Oh, that’s me.’

“Books were always my best friends,” she said. “I didn’t have very many people who looked like me, so I found a lot of friends in books.”

Wong, 43, who lives in West Chester, has realized her childhood dream of being a successful novelist. Booklist called her first Young Adult book, “None of the Above” (Harper Collins 2015), about a teenage girl who discovers she was born intersex, “[a] remarkable novel … eye-opening and important.” And in a starred review of “This Is My Brain in Love,” Publishers Weekly wrote, “Readers will come to this story for dynamic romantic and familial relationships, but they’ll stay for its smart exploration of depression, anxiety, and self-care.”

Not bad for an author who has a demanding day job: Wong, a physician, is a urologist who sees patients at Chester County Hospital, Paoli Hospital, and Brandywine Hospital. She’s also a mother of two children — a 10-year-old girl and a 6-year-old boy — in a racially diverse family: Her husband, Joseph Gregorio, director of choirs for Swarthmore College, is Italian American.

Like the protagonist of “This Is My Brain in Love,” Wong battled for years with how to deal with depression before finally accepting medication as a part of her life. She says her own children were among her main reasons for writing “This Is My Brain in Love.”

“More than anything, I wanted to show my kids that if they ever have any of these struggles, they are not alone and there’s nothing shameful about it,” Wong said. “Having mental illness does not mean you can’t be successful and you can’t ultimately be happy.”

Wong learned that the hard way. She first sought help for depression when she was in college and then at several other times during her medical training. But she went in and out of therapy, and on and off medication, despite severe inner pain. At one point, her depression was deep enough that she felt it wouldn’t be so bad if a car ran a red light and put her out of her misery.

But she felt uncomfortable talking about it. Two decades ago, mental illness wasn’t discussed as openly as it is today, nor with much compassion.

“I grew up in a house where crazy was a bad word,” she said. “I was raised to be strong and resilient.”

In her own family, a cousin who died by suicide was spoken of only in hushed tones. For many first-generation offspring of immigrants Wong has spoken with since, they acknowledge that, in their families, too, depression is seen as an ‘American disease.‘”

The culture of the medical profession didn’t make it any easier for Wong to accept that she needed medication and help.

“There’s nothing you could say that’s a bigger compliment to a surgery resident than that they are strong, or they’re a machine,” she said.

It wasn’t until she was a doctor herself that she realized that her emotional nature — and the empathy and sensitivity that went with it — was not a weakness but a strength that helped her to help her patients.

It was while she was a resident at Stanford University that her psychiatrist told her matter-of-factly that her brain just needed serotonin. It finally clicked with Wong, but what it took to convince her still has her shaking her head.

“I was already a doctor, and I was denying myself medication,” she said.

Something else important happened during Wong’s Stanford residency: She met an intersex patient who would become the inspiration for the main character in “None of the Above.” The story dealt with issues like gender, bullying, and sexuality, as Wong’s second book explores mental health, racial and ethnic identity, and relationships.

In the latter, Jocelyn, who is first-generation Chinese American teenager, is experiencing the awakenings of romance with a boy who is African American and Italian American. Both of them are dealing with mental health issues and other pressures. If that sounds a little complicated, you might also just call it adolescence, which is what it reads like.

What it’s also called is “intersectional diversity,” and for Wong, that’s intentional.

“When I first started writing, conventional wisdom was that you could have too much diversity in a book,” she said. “It would come out in reviews. Even today, sometimes you’ll see that.”

Wong, a passionate advocate of diversity in books, is a founding member of We Need Diverse Books, a nonprofit started in 2014 and aimed at changing publishing by supporting authors of color, encouraging diverse writers to publish, and advocating for diversity in content.

One of her earliest experiences at trying to get her work published still makes her bristle. Before either of her books made print, she had written a novel about an Asian American girl much like herself and her later character, Jocelyn Wu. She got some positive responses from editors, but they passed on the novel because they said it was too much like other Asian American books they were publishing.

“That was like a slap on the face,” Wong said. “All my Asian stories were just a quota to them.”

Thanks to the self-empowerment of social media, We Need Diverse Books organized, built a community, and has grown to be a support network for diverse authors and diverse stories. Wong is proud of that. As time goes on, there may be more and more books for children who need the friendship of books like she did, or kids with diverse backgrounds who may enjoying reading about kids like themselves. Or any young people regardless of who they are, who read a book like “This Is My Brain in Love” and find something meant for them to hear.

“I really hope this book is for everybody,” Wong said. “That it reveals things to them that helps them better navigate their own lives.”