This schoolteacher trained 56 guide dogs - and now her students do, too

Over five decades, she has raised 56 dogs to assist visually impaired people. But her legacy doesn’t end there: She has inspired family members and dozens of former students to do the same.

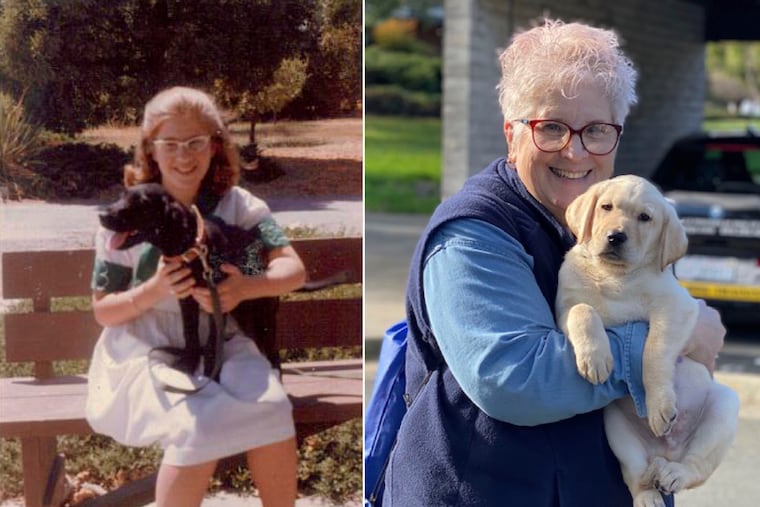

When Marybeth Hearn was 10, she asked her parents if she could train a puppy to become a guide dog. It turned into a lifelong mission.

Over more than five decades, Hearn has raised 56 dogs to assist visually impaired people. But her legacy doesn’t end there — the longtime, recently retired high school teacher has inspired several family members and dozens of students to turn out many more.

“I like doing something good for somebody I just haven’t had the chance to meet yet,” said Hearn, who in December ended 33 years of teaching agriculture at Lemoore High School in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

When she approached her parents decades ago, prospects seemed unlikely. Her mom didn’t like dogs, and her dad secretly doubted she would be able to find a sponsor to pay for the cost of the training.

Hearn was so determined, however, that she presented the project at a Lions Club and raised $2,500.

And so on a sunny summer day in 1962, the family drove home with a black Lab named Letta barking in the backseat, the first of a long string of puppy trainees.

Two sons and a granddaughter have followed in Hearn’s footsteps, but her greatest impact has come from mentoring a generation of student trainers who since 1992 have worked with 170 dogs that ended up in a range of service posts.

They spend 14 months with each puppy, teaching them skills like house-training, walking on a leash and behaving themselves in public. The dogs live full-time with the students, attending their classes and field trips to become socialized.

“If you can imagine a classroom with 21 under-a-year-of-age puppies and 30 kids, it’s quite the extravaganza,” Hearn said.

The dogs then move to certified trainers employed by Guide Dogs for the Blind, a national NGO that partners with the program, before ultimately graduating and being paired with two-legged companions. Those that aren’t up to the difficult task of assisting the blind can end up as other kinds of service animals.

Often students attend the graduations and help ceremonially pass the dogs on.

“I love to see the look on the kids’ faces ... when they get to see that dog again after three or four months and the dog remembers them,” Hearn said. “It’s a great feeling.”

Even after classes went virtual in March due to the coronavirus, the program continued and has since turned out 12 puppies.

Students came to the school for what Hearn called “socially distanced play dates” in the fields, with everyone masked up and 6 feet apart and puppies “running all over the place with their toys.”

“It was great because it gave the kids a way to communicate with each other and not be so completely isolated,” she said.

Guide Dogs for the Blind CEO and president Christine Benninger said Hearn’s work has had a “tremendous positive impact” for the NGO, which annually graduates about 300 dogs to play a role that has only become more vital this year.

“Blindness isolates you to begin with, and now with COVID we’re even more isolated,” Benninger said. “So just for one’s mental health or companionship, having a reason to get up and go somewhere every day, having a guide dog is life-saving for some of our clients.”

The program also imparts to students the value of giving back to the community.

Hearn “put Lemoore High School on the map,” principal Rodney Brumit said, “as far as being a school that supports service to others.”