Philly stargazers reflect on the moon landing, 50 years later: Where they were, what it meant, and should we go back

Plus: Seven events to celebrate at, from downtown to Doylestown.

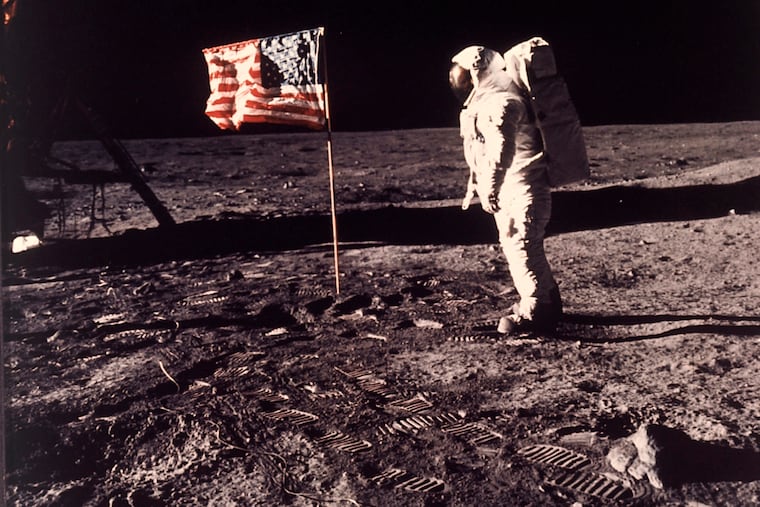

Fifty years ago Saturday, human beings first set foot on the surface of the moon.

We asked local stargazers of a certain vintage where they were, what it meant, and whether we should go back.

Derrick Pitts, astronomer

Of course Derrick Pitts remembers where he was when Neil Armstrong’s boot touched down on the dusty lunar surface. Now an author and the chief astronomer at the Franklin Institute, Pitts was back then a 14-year-old kid with his eyes glued to the 21-inch black-and-white television screen in his mom’s bedroom in their North Philly apartment. They had the lights out, to give the grainy footage some contrast.

Even then, Pitts was an above-average space nerd, and had followed along with the progress of Apollo missions since he was little. Still, the experience blew his mind. “I was completely amazed that this was happening,” he says.

The country shared excitement, he recalls, but memories of Apollo 1 bursting into flames on the launchpad two years earlier were not far from people’s minds. “There was all kinds of danger. There was every possibility that all kinds of things could go wrong,” he says, but he took comfort in the space agency’s well-documented redundancy policies. “If one system didn’t work, they had a workaround already built in that they could go to.”

Despite the dangers, Pitts says we should absolutely return to the moon. In total, the Apollo missions put people on the lunar surface six times, but “we still only saw an extremely tiny portion of the moon."

“Space is a nasty place to be,” he says, but the space program has been worth the risk, since it drives technology and gives us some much-needed perspective. “As it turns out, the more we study other places around the solar system, the more we realize how incredibly special this particular place — Earth — is.”

Through programs like Night Skies in the Observatory at the Franklin Institute, Pitts does his part to stir up excitement for space exploration. “But I’m a small voice.”

True, but he’s got a pretty big telescope.

Ken Kalfus, author

In his 2014 novel Equilateral, Philly-based author Ken Kalfus imagined what it would have been like for the best minds of the Victorian era to attempt communication with Mars. Their plan is to painstakingly dig a 300-mile triangular ditch in the Egyptian desert, fill it with oil, and light it on fire. It’s an amazing image that sticks with you.

Kalfus’ interest in space is long-standing. He grew up in Long Island — “not far from where they built the lunar module” — and remembers waking up to watch the Eagle landing as a 15-year-old. “I think I was the only one in my family who bothered to do that. Really, not everyone in America was quite as excited about it as they’ve now been made out to have been. But I was thrilled, and I still am when I think about it.”

What did it mean, putting humans on the moon? “It was a terrific expression of human ingenuity, and some of the rocks brought back have changed our understanding of how the Earth itself was formed,” he says. “I don’t know [if] it has more implication than that, regardless of the pompous pronouncements made at the time and this week. Still, I’m glad we did it. It was great fun.”

He doesn’t see much point in sending people back to the moon, since robots can do the trick for cheaper. “For NASA, human space flight is a distraction and a huge money suck. I doubt private enterprise is going to find it profitable.”

Sonia Sanchez, poet

There’s a memorable moment in the 1996 movie Contact where Jodie Foster’s character gets her first clear view of the beauty of the cosmos and, unable to put the experience into words, declares, “They should have sent a poet.” That’s why we reached out to award-winning poet and Philadelphian Sonia Sanchez.

“They wouldn’t send a poet — that’s the whole point,” she says.

Sanchez, who was 34 and living in Harlem at the time of the moon landing, doesn’t recall staying up late to watch it; she figures she caught the replay later. She and the other writers in her circle kept their concerns grounded. Peace, poverty, civil rights, human rights — these were the things that they wrote and marched about.

“We weren’t going to change this Earth unless we began to ask people to examine the question of ‘What does it mean to be human?’ and not necessarily ‘What does it mean to be going out into outer space?’ ”

As for Sonia Sanchez circa right now, she still doesn’t see much value in space travel. The money could be used to fix the environment and rescue children in migrant camps along the southern U.S. border, and we can concentrate on “the exploration of our souls and our neighborhoods,” she says. “Maybe I’m just an Earth woman, you know, with no real interest in going up into outer space — until we get the correct people … so we don’t take the virus of non-respect and non-love for another human being someplace else.”

Samuel Delany, author

Temple professor and esteemed sci-fi author Samuel “Chip” Delany watched the moon landing as a 27-year-old at Rochdale College (an experimental, student-run university in Toronto, now closed).

“I’d been reading about it for years in science-fiction, and there it was, finally happening. For a little while, people were really nice to Americans, congratulating us in the street for what ‘we’d’ done.”

It also changed the way people looked at the moon. “Before, it had been the essence of something alien; now, it was a place where human beings had actually gotten down on, walked around, and come back from.”

Delany has set several of his brainy, funny, out-there novels in the depths the cosmos, but his best-selling Dhalgren from 1975 specifically mines his moon memories. “I am one of the few people who accurately recalls Neil Armstrong’s first words from the surface of the moon (I wrote it down in my notebook): ‘I’m at the bottom of the ladder now,’ before his famous, mangled one-liner. I’ve always felt his actual first words were far more meaningful than the ones that are always talked about.”

Delany says humans should return to the moon. “We’ve sent rovers to the surface of Mars and gotten close-up pictures of Jovian satellites and various Saturnian debris, but I think people have a place in all this, too, though I’m glad they’re doing it with some caution. The tragedies involved are already pretty great, such as the [Space Shuttle] Challenger disaster and the death of the teacher, Sharon Christa McAuliffe, and the other six crew members. And the first six monkeys, Alberts I through VI, didn’t have very good luck; in short, they died.”